A new study suggests that a creature with no anus is more similar to penis worms and mud dragons than to humans.

The 500 million-year-old Saccorhytus coronarius was once tied to a group of animals that produced humans. A new research team has decided that it's an ecdysozoan, a group that includes insects and marine animals such as penis worms.

The researchers said that the new findings make an important amendment to the evolutionary tree.

Philip Donoghue, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, told Live Science that the team was always confident that S. coronarius needed reclassification. Some people were relieved that we weren't descended from ball sacs.

The mammal's ancestors looked like a lizard with a small head.

In the Shaanxi Province of Northwest China, there are small fossils of the early Cambrian species. Detailed X-ray images of the fossil were produced by using a type of particle accelerator called a synchrotron.

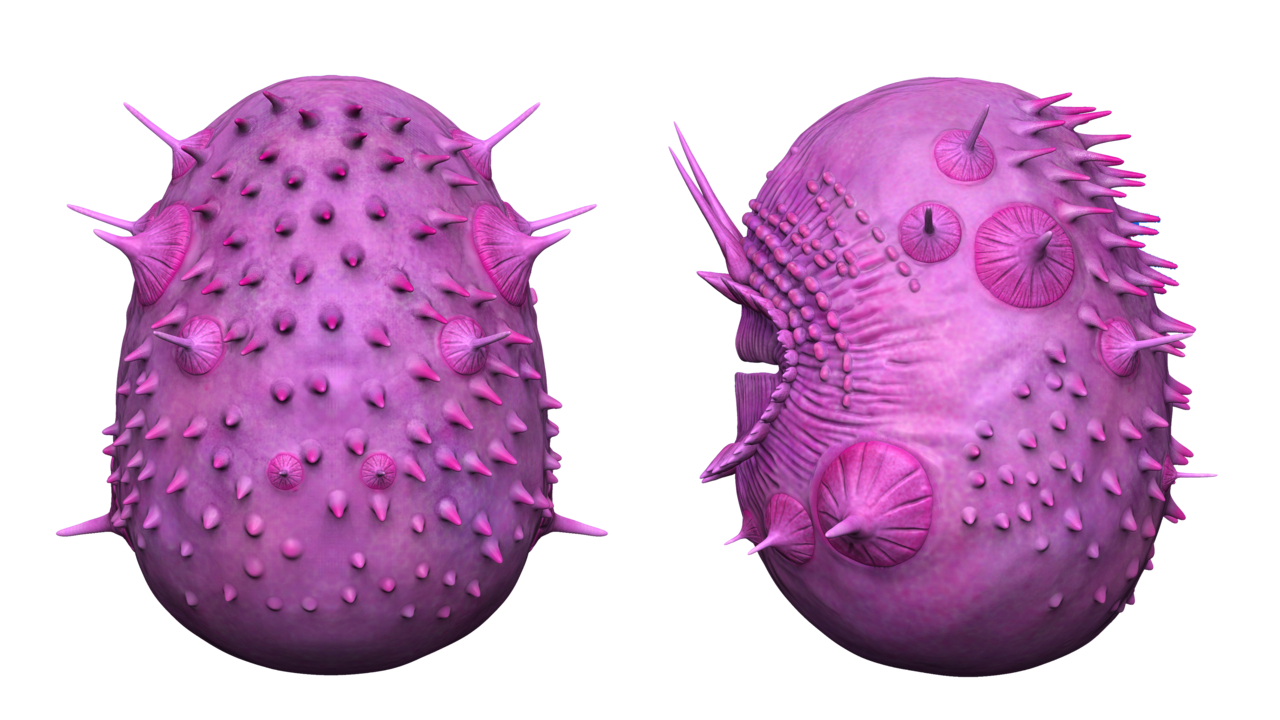

According to Live Science, the original interpretation of S. coronarius concluded that the holes around it's mouth could be used to make gills. According to the new research, S. coronarius had spine that broke off during fossilization.

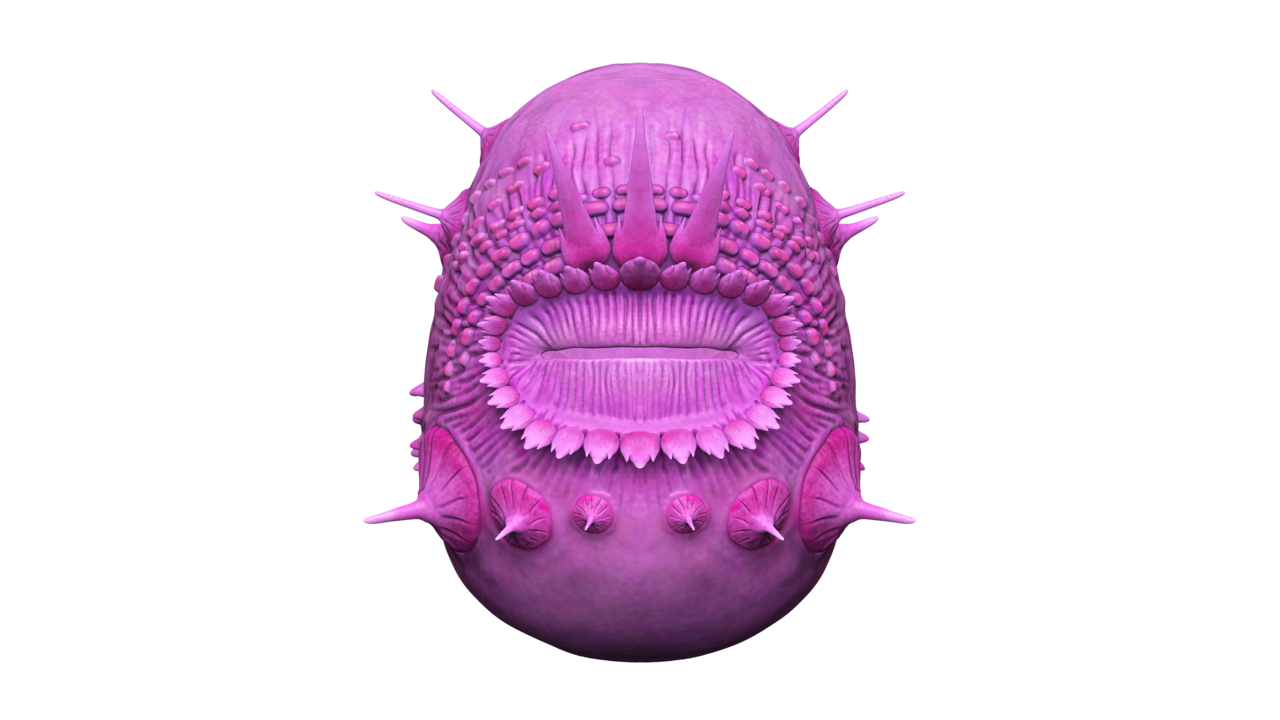

The team created a 3D model of S. coronarius and compared it with other animals. It's a big move for the little creature and could lead to a scientific debate.

There is still room for interpretation with S. coronarius according to a paleobiologist at Harvard University. I don't know if I'd go as far as to say that this is a full-on correction of the research done last year, he said. Both of them are interesting and worthy of debate.

It was described as having a lot of components that make it difficult to understand. He said it was old, weird and small. Major understanding can change with the smallest details.

Most major animal groups make their first appearance in the fossil record sometime around that time or shortly after. Even small interpretations of 'is this a spine that's been broken off or is this a true actual opening into the animal' have huge ramifications for how we interpret the origins of these major groups.

The lack of anus is important because it contributes to the understanding of body plans. There may be more body plans waiting to be discovered as a result of the new research.

Scientists still have a lot to learn about ancient creatures like S. coronarius, even though they could have spent their days catching prey on the sea floor.

They have a mouth and no anus, but we don't know much else. After they finished processing it, whatever came out of their mouths had to come out. It's a weird way to live, but it worked for them.

The study was published in Nature.

It was originally published on Live Science