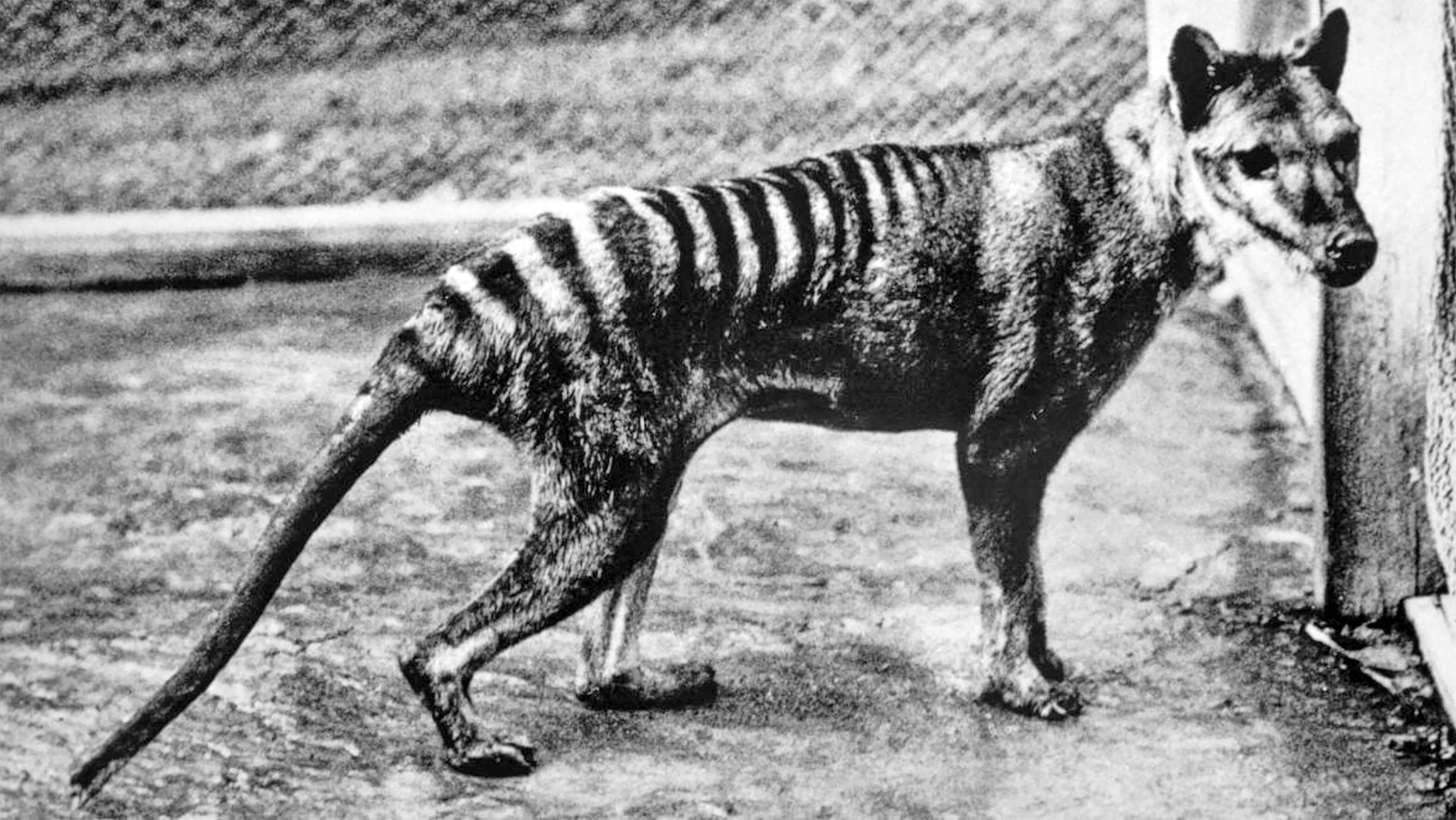

The thylacine is an icon of extinction caused by humans. In the 1800s and early 1900s, European colonizers wrongly blamed the dog-sized, tiger-striped, predatory animals for killing their sheep and chickens. The settlers traded the animals' heads for government bounties. The last known thylacine was neglected and died in 1936.

The wolflike creature, also known as the Tasmanian tiger, is poised to become an emblem of de- extinction, an initiative that seeks to create new versions of lost species. The company that made headlines last year when it said it was going to bring back the woolly mammoth will be resurrecting it.

Australian scientists have been trying to bring the thylacine back from the dead for over a decade. The top predator went extinct in the state. According to some researchers, re-introduction of proxy thylacines could help restore balance to the remaining forests by picking off sick or weak animals. The effort to clone the animal from its museum genetic material failed and did not attract much funding.

George Church, co-founded by Harvard University geneticist George Church and tech entrepreneur Ben Lamm, is working with the University of Melbourne's Andrew Pask on a project. The thylacine is a perfect candidate for de-extinction because it has died out, good-quality DNA is available, and its prey and parts of its natural habitat still exist.

A philanthropic gift of five million Australian dollars was made by his team in March. Colossal is giving more than that sum, as well as access to equipment and a large team of researchers.

It is reasonable to think that in a decade there will be a de-excavated tylacine-ish thing. He says the first iteration may be "90 percent thylacine." After many years of monitoring the engineered animals in a large enclosed area, Colossal hopes to release a viable, genetically diverse population into the wild.

The asian elephant is the closest living relative to the woolly mammoth. They will attempt to create an embryo with modified genes that could be used to create an artificial uterus or elephant-surrogate. Lamm says the creature would not be a mammoth but a cold-adapted "Artic elephant" with small ears, shaggy hair, a domed forehead and curved tusks. If he showed it to his grandmother, she would call it a woolly mammoth.

Colossal has already mapped the Asian and African elephants, collected more than fifty mammoth genomes, and begun making edits to elephant cells, but Lamm thinks it would be easier to revive the thylacine than the mammoth. Both projects face a lot of obstacles.

The first thing the animal needs to do is have its genome mapped. The lab has about 96 percent of it down, but the last 4 percent is difficult. It is like doing a horrible puzzle that is all baked beans or blue sky. We are trying to figure out how it all works.

Next, the researchers will compare the genome of the thylacine to that of the fat-tailed dunnart, a mouse-sized mammal that is abundant and can survive in captivity. The scientists will use the technology to modify the dunnart's genome to make it look like the thylacine's.

The researchers have figured out how to reprogram dunnart skin cells into stem calls, and are testing them to see if they can create an entire embryo. They will be able to use stem cells to create a living embryo, but they will have to create an artificial womb.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

The average length of a thylacine pregnancies is just a few weeks, compared with 22 months for mammoths. The baby thylacines are small, so even a small mother could feed them in her pouch at first. Colossal will work on developing a synthetic pouch and a milk formula that is appropriate for each stage of development.

The new reproductive technologies could become important tools for the preservation of koalas and numbats. If I didn't try to bring the tiger back, I wouldn't have the millions that I have now for the preservation of the animals.

Some scientists are less positive about the project. Kris Helgen, a mammal expert from the Australian Museum, thinks it will be difficult to change the dunnart's genes to look like a thylacine. He says the species are separated by 40 million years of evolution. Dogs are in one family of mammals and cats are in another, but Thylacines are so different that they are in their own family. It would be the equivalent of editing a dog's genome until it turned into a cat. Ammoths and elephants are very similar.

Even if Colossal could surmount the technical challenges involved, the prospect of resurrecting the thylacine raises ethical concerns. She says that the welfare of the individual animals isn't talked about in the discourse. dunnarts and almost-thylacines will inevitably suffer in the course of these experiments, which cannot be justified. It would be many years, if ever, that cloned animals could have the life they deserve in the wild.

The public and Indigenous communities would be consulted about any release if the scientists get to the point where they have living thylacines. Bradley Moggridge is an environmental scientist at the University of Canberra in Australia. They might need to prepare their traditional lands for this species. It might take a long time. Moggridge believes that discussions between the Colossal team and Indigenous Australians could benefit everyone. The researchers need to start those conversations now because the stories and songs about the thylacine would have been written by the aboriginals.

The glamour of de-extinction is worrying other critics. The study found that allocating sums to existing species programs would see about two to eight times the number of species saved than by giving the same amount of money. Joseph Bennett told Science that it was better to spend the money on the living rather than the dead.

The idea that science could restore the thylacine is lovely, and it captures the imagination, says Helgen, who once made a pilgrimage to visit every museum specimen of the animal. There is no way to bring back the extinct species of horse. The thylacine is one of the species that are gone forever because of their unique nature. We're not going to get an escape hatch from extinction.