There are many insects in the trillions. They're a major part of the global environment, helping to move food and plants across the globe.

It had been thought that insects mostly went where the wind blew.

How they react to different wind conditions while on their way has been an outstanding question.

The death's-head hawkmoth is a migratory insect that can maintain a straight flight path. The moths are able to adjust their trajectory.

Direct observations give us much of our knowledge of insect migration.

Observations made using radar, or studies of population processes, such as using genetic methods, or measuring ratios of isotopes in tissues, can reveal insects' food and water sources and provide information on where they come from.

The sheer number of insects has made it difficult to study how individual insects behave. Tracking technology has made it possible to produce transmitters small enough to be carried by larger insects.

The transmitters weigh less than a gram. This will allow us to learn more about the process of migration.

The death's-head hawkmoth is an insect found in Europe and Africa. The species has a skull-like mark on its thorax. It has a bright yellow abdomen and has a habit of making noise when disturbed.

The insect pierces the honeycomb with its proboscis and feeds on honey it stole from honeybees.

This species is found in Europe, but little is known about where it spends the winter.

Adult moths tend to appear in Europe during May to June, and the next generation of adults set out in August to October, likely going to the Mediterranean or North Africa.

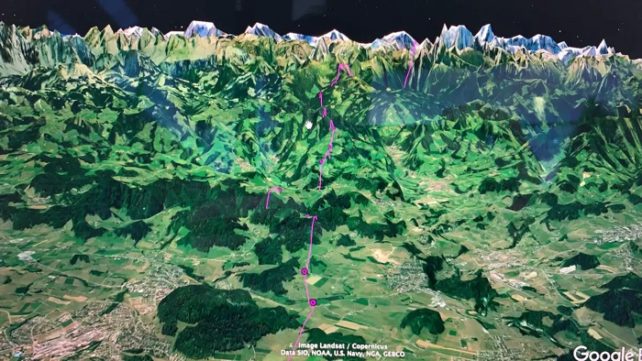

It is thought that the species is unable to spend winter in the north of the Alps because of low temperature.

We were able to track 14 moths for up to four hours each, which is enough time to be considered migratory flight.

Each person was fitted with a small radio transmitter before they were released. As they migrated, a plane with receiving antenna flew after them, detecting their exact location every 15 minutes. We were given in-depth insight into their flight behavior.

The monarch butterfly and the green darner dragonfly are two day flying insects. It hasn't been used on nocturnal insects in the wild.

Our research shows that the longest distance any insect has ever been tracked in the field has been recorded by us.

What do moths do when they migrate? We were surprised to find they flew along very straight paths. Over the course of four hours, some of the longest tracks went over 90 km.

Straight tracks are very rare in long range migratory animals.

Different strategies were shown for dealing with different wind conditions. When the wind was blowing in the same direction as them, they flew in the opposite direction and were propelled towards their destination.

The moths flew low to the ground in unfavorable conditions to avoid drifting off course. They increased their speed to make sure they stayed in control.

The death's-head hawkmoth is able to stay on course even in bad conditions.

We have shown that insects are capable of being expert navigators and that they aren't at the mercy of the winds. This is an important discovery.

We don't know a lot about how insects move. The next step is to understand how these insects stay on their way. Are they following the Earth'smagnetic field? Is it possible to rely heavily on visual clues?

The closer we are to being able to predict insect migration, the better. Managing threatened species and having better control over agricultural pests are some of the broad implications of this.

Myles Menz is a lecturer at James Cook University.

Under a Creative Commons license, this article is re-posted. The original article is worth a read.