Black holes crash into each other much more frequently than we thought. Black holes can be merged quickly if they are caught in the accretion disk of a super massive companion.

It is easy to get two black holes close to each other. Either they are born that way or randomly meet each other in the depths of space. They can stay around each other for a long time once in space.

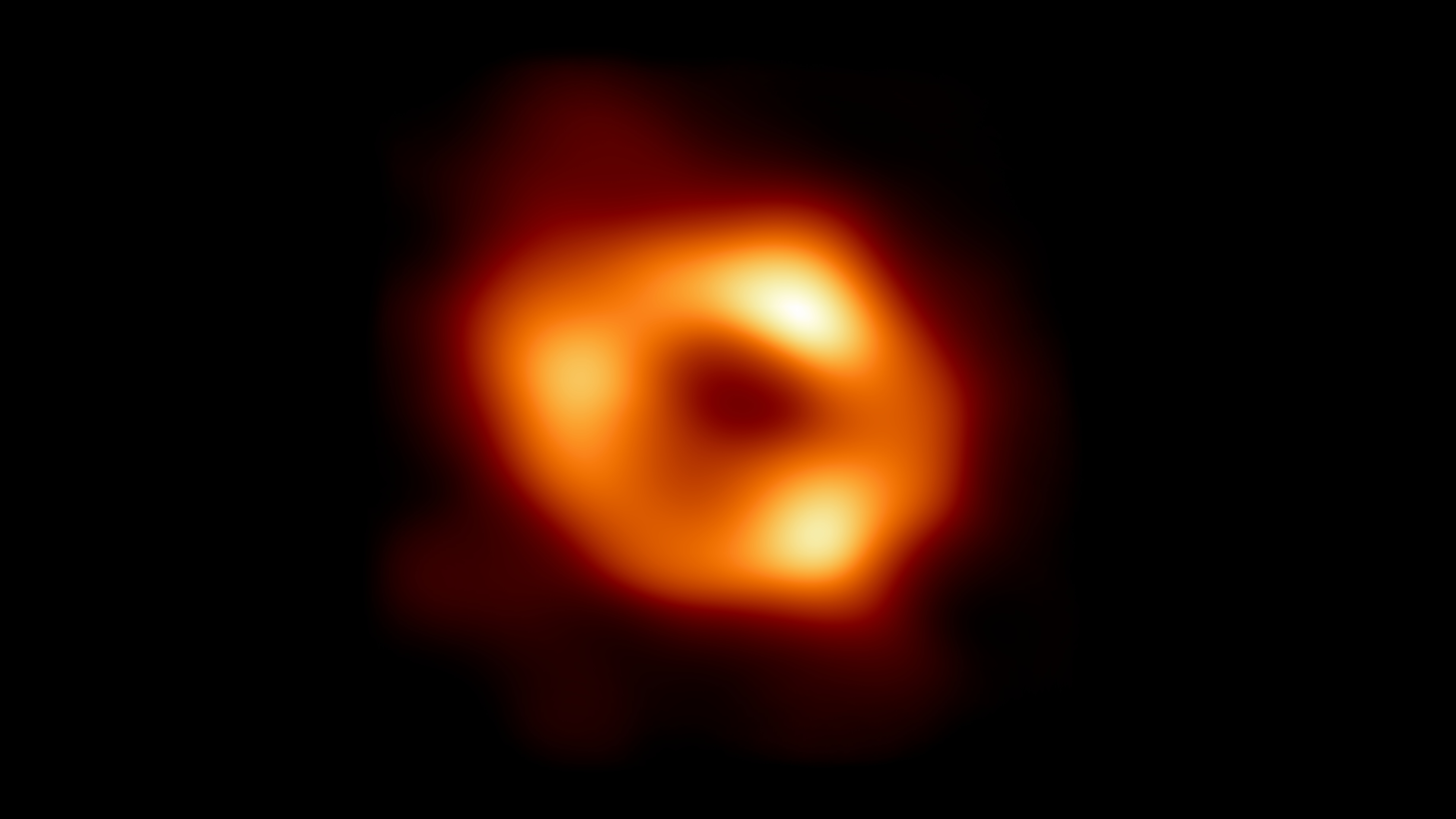

Astronomers knew that black holes would eventually meet a fatal end, even before the detection of the ripples from merging black holes. We know that large galaxies grow from the collective merging of many smaller galaxies and that almost every galaxy in the universe is home to a giant black hole. Each galaxy has one giant black hole, which tells us that if there is a merger, so too will their black holes.

There are two monster black holes merging into one.

It is difficult to get black holes to hit each other. To get two objects closer together, you have to move away from the system. This is a difficult job because of space's ease of use. The emission of radiation or gas is what planetary systems do all the time. There is no such option for black holes.

When the two black holes are very close to each other, the process of pulling energy and momentum out of a system is possible. The final parsec problem is the difficulty in getting black holes close enough to allow the waves to drive the merger.

Astronomers have come up with a variety of solutions to the problem. The presence of a third object is usually involved in these mechanisms. With just the right alignments and speeds, the third companion can tug on the binaries, stretching out their circle. The ellipticality of the black hole is increased. The black holes are spending more and more of their time together. Black holes finally merge when they reach a critical distance.

That scenario needs a precise configuration for the third companion. Astronomers estimate that there are between 15 and 38 black hole mergers every year in the universe, and that there are mechanisms that depend on a third companion.

Researchers propose a new way of merging black holes in a new paper. It is more generic than the reliance on a distant third companion.

A setup begins near a black hole. There are many smaller black holes in the center of the galaxies, which are crammed with stars. We can probably find a lot of black holes around the central one.

The authors of the paper discovered that there is a chance for a merger if the binaries are tilted around the black hole. The axis of their rotation has to be precessed first. If the rate of that precession matches the period around the central black hole, then its enormous gravity will tug on the binaries, causing their eccentricity to increase and heightening the chance of a final merger.

It has to be a very lucky coincidence for that type of matching to happen. Nature is capable of taking care of that. The black holes will migrate if they are in the disk of the black hole.

They will eventually find a distance that matches their precession period even if they start out in a different direction. The gravity of the black hole will increase if they hang out there for a long time.

This is a generic scenario. They discovered that black holes merge when they ran many simulations.

It's not clear if this is the primary mechanism by which mergers happen or if it's just one of the many ways. The work shows how complex the lives of black holes can be and how they can dance in the dark.

We encourage you to follow us on social networking sites.

You can learn more by listening to the "Ask a Spaceman" and "Askaspaceman.com" radio shows. If you want to ask your own question, you can use the #AskASpaceman or follow Paul on social media.

We encourage you to follow us on social media: