There are a lot of photos of civilians killed or injured in the Russia-Ukraine war.

During times of crisis, editors have always published pictures of dead or dying people. The current crisis has resulted in more of these images being published online.

Nancy San Martin was a foreign correspondent and editor at the Miami Herald. Not just on the internet. Mainstream journalists are no longer avoiding the use of images of dead people or depictions of physical injuries.

San Martin, deputy managing editor for the history and culture desk at National Geographic, told me in a phone interview that war will always open that door. Documenting the consequences of war is one of the things we do.

The practice of a group of journalists who balance the significance and importance of an image with its gruesomeness has historically been part of the equation. They could choose a different angle of an injured or dead person that shows less blood, crop an image so a dead person's face isn't visible, or refuse to show an image at all.

Images can become public icons and symbolize major events.

There are a lot of images from the war. It shows more carnage than has been seen in previous conflicts.

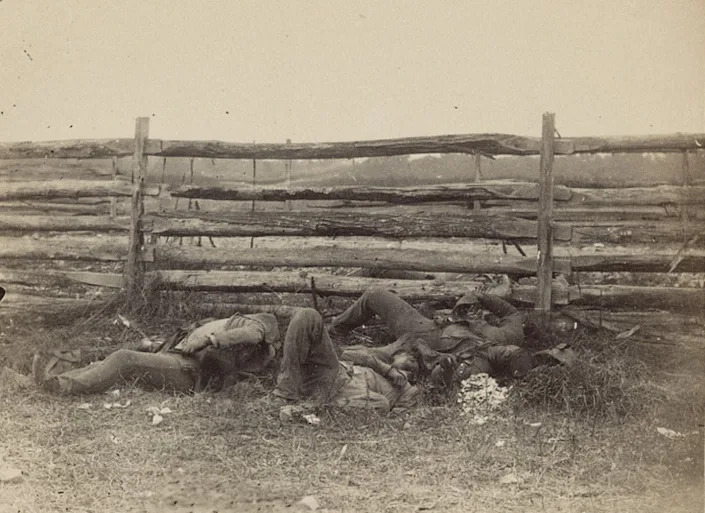

During the U.S. Civil War, war was a common topic.

Some images have become famous, such as Joe Rosenthal's picture of the Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. It ran on the front pages of many newspapers in the United States.

Patrick Farrell told me in a video call that there have always been powerful images from conflict. One of the most powerful forms of media is a picture. It will stay with you for the rest of your life.

Many of the famous images are not of victory or glory, but rather of violence and death. Both the foreign and domestic toll of the Vietnam War can be seen in the photographs of Nick Ut and Kim Phuc. They were used to feature in newspapers and magazines across the country.

Editors across the nation chose to show the real human cost of natural disasters by including photos of bodies in the streets after the earthquake in Haiti and the flooding in New Orleans.

The image of a vulture next to a starving child in Sudan was published by editors worldwide. In 1994, it won a Pulitzer Prize.

The image of AylanKurdi, the Syrian boy whose lifeless body washed up on a Greek beach, is one of the photos distributed by wire.

The volume of images is different between those situations and the current one in Ukranian.

In conflict situations, award-winning professional photojournalists in Ukranian send their images to the media outlets they work for. Many of them are also posting images on their own or their employers' social media accounts, more images than might be published on a newspaper's front page or website.

Ordinary citizens take pictures with their phones and share them on social media.

Farrell said that the media environment in 2020 is different from previous decades because of the floods opened by social media. Many powerful images are competing for the attention of the public.

Farrell thinks it is not more graphic than what we saw during Vietnam, but the media cycle at the time meant there were breaks in the onslaught of imagery.

There is less editorial oversight about which images reach the most eyeballs in newsrooms.

With social media in the mix and the never ending competition to be first, editors are publishing and distributing images with less consideration for traditional editorial restraint and balance between gore and meaning.

San Martin said that in some ways life goes on. She says that despite the carnage of war, the places where people live are still there. Joe Raedle, her husband, is an award-winning photographer who has been on the ground in Ukranian documenting both the refugee exodus and the everyday life of the people.

There is a different type of war. She says that there is more going on than what is shown in the images. She believes that those elements will become more important as the war continues. It is going to take a long time.

It is normal for the media to highlight the most dramatic and tragic events. The survival, determination and resilience of those affected are what San Martin reminds me of, and what I have observed in my work.

Sensational images that are shared on social media are incomplete. It's an important reality that they represent. There's more to the picture than that.

The Conversation is a news site that shares ideas from academic experts. Beena was the author of it.

You can read more.