The Conversation contributed the article to Space.com's expert voices.

Jack Baggaley is a professor of physics and astronomy.

New Zealand seems to be under a lot of meteorites. There was a sonic boom that could be heard across the South Island after a large meteorite exploded above the sea in Wellington on July 7.

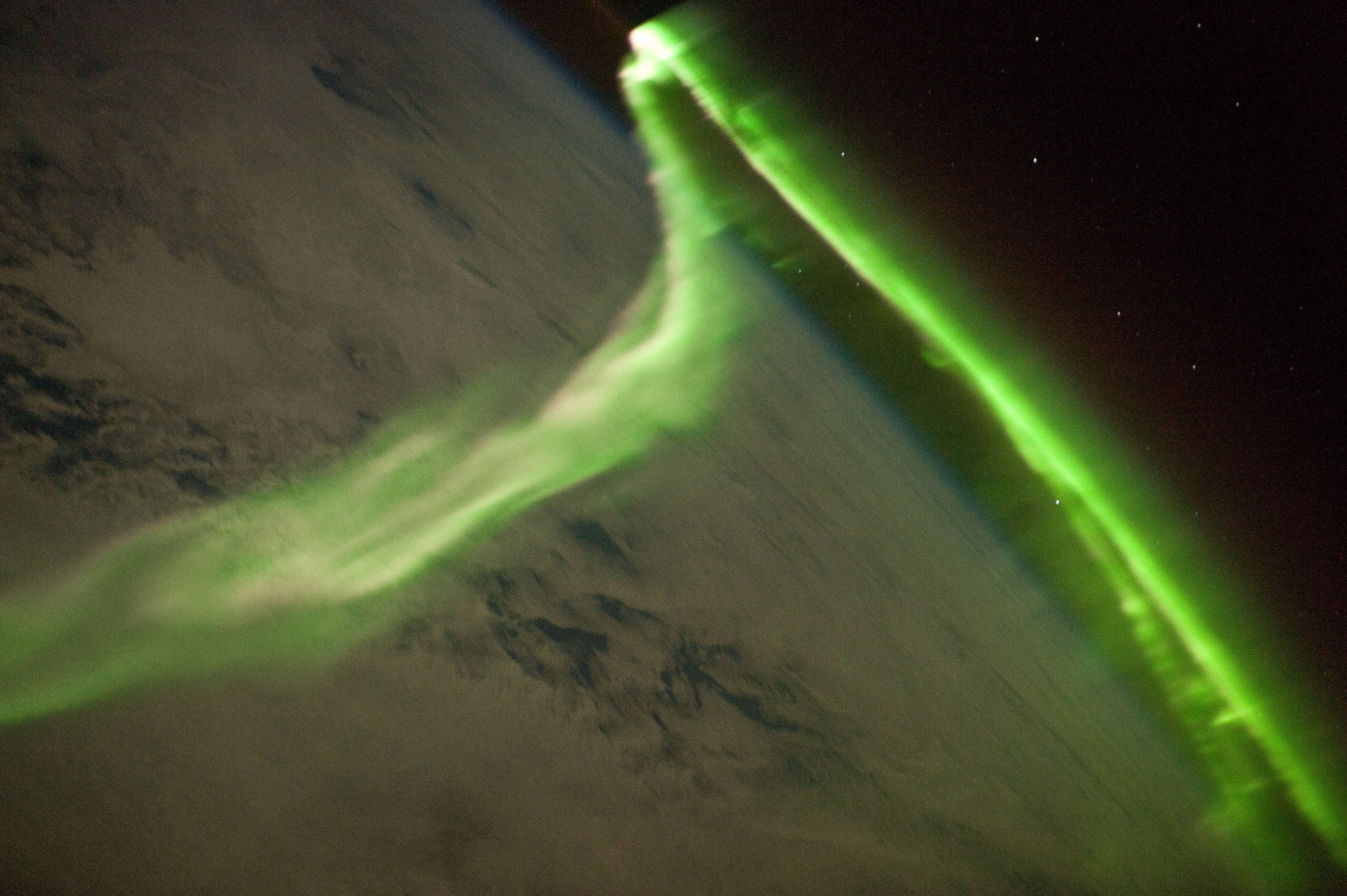

Fireballs Aotearoa, a collaboration between astronomer and citizen scientists which aims to recover meteorites, has received a lot of questions. One of the most frequently asked questions is whether the green is the same green produced by the Auroras.

There have been green fireballs in New Zealand. A chunk of an asteroid can be anywhere between a few centimeters to a meter in diameter when it crashes through the atmosphere.

At speeds of up to 60 km per second, some of the asteroids contain nickel and iron. The iron and nickel emit a green light.

Is this the same as an Aurora? The answer is mostly no, but it isn't that simple.

The green glow of the Aurora is caused by the creation of oxygen ion in the upper atmosphere.

The electrons can stay in an excited state for a long time. The energy transition known as "forbidden" is an energy transition that doesn't obey the usual quantum rules.

If it's fast, a meteorite can shine by this route. In the thin atmosphere above 100 km, there are very fast meteors.

If you want to see a green wake from a meteorite, watch out for the Perseid shower, which will peak in August.

The comet Swift-Tuttle arrives at about 60 km per second. At the beginning of their path, there is a green wake behind them.

The pale yellow glow at the end of the trail was caused by the winds of the upper atmosphere twisting it. This is caused by sodium atoms being excited.

As seen from Moana, looking across Lake Brunner pic.twitter.com/ajT3YMwaqvJuly 21, 2022

You can see more.

In New Zealand, big, booming green meteors and the dropping of meteorites aren't uncommon, but they're rare to recover. The recovery rate is being improved by Fireballs.

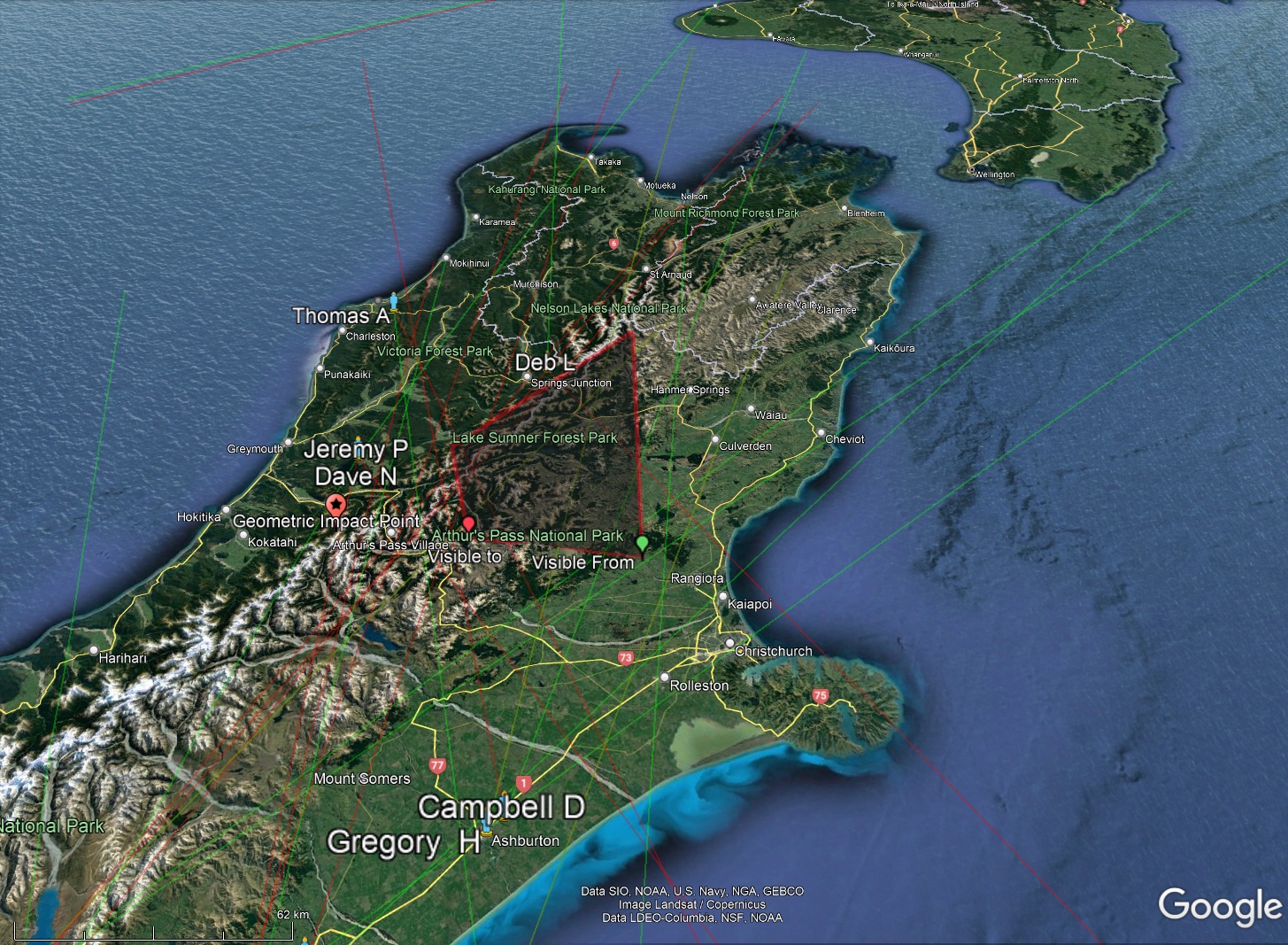

Four meteorites may have hit New Zealand. Citizen scientists are encouraged to build their own camera systems so they can watch the events.

By looking at the images from multiple cameras and comparing them to the stars in the sky, we can figure out the location of the meteorite.

It helps us find the rock, but it also tells us what part of the solar system it comes from. If you want to sample the solar system without having to launch a space mission, this is a good way to go.

There are more than a dozen meteor cameras in the South Island. We're looking for more people in the North Island to build or buy a meteor camera and keep it pointing at the sky.

Next time a bright meteorite explodes over New Zealand, we might be able to pick it up and do some good science with it.

Under a Creative Commons license, this article is re-posted. The article is open in a new tab.

Become a part of the discussion and follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates on social media. The author's views do not represent those of the publisher.