The bright iridescent colors in butterfly wings or beetle shells don't come from any pigments, but from how the wings are structured. It can be difficult to scale up the process for commercial applications without sacrificing optical precision, but scientists can make their own structural colored materials in the lab.

MIT scientists have developed films that change color when stretched. The method is easy to scale and preserve optical precision. Their work was described in a paper.

Scales of Chitin are similar to roof tiles. The entire spectrum of light is produced by a diffraction grating, which is a type of grating that only produces specific colors and wavelength of light. The term tunable refers to the fact that the crystals are ordered to block certain wavelengths of light. The structure can be changed by changing the tiles' size.

Materials research involves creating structural colors like those found in nature. Structurally colored materials that change hue in response to mechanical stimuli would benefit from use. None of the methods used to make such materials can control the structure at the small scales required and scale up beyond lab settings.

Advertisement

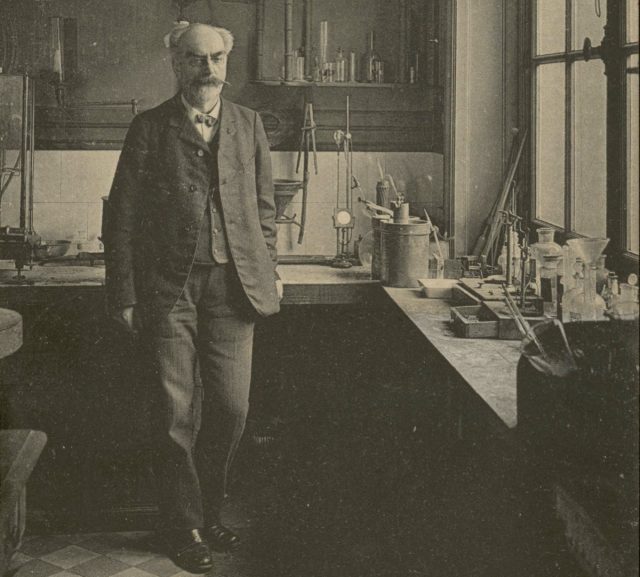

Benjamin Miller, a graduate student at MIT, discovered an exhibit on holograms at the MIT Museum and realized that they were similar to nature's structural colors. He was able to learn about the history of color photography and the invention of Gabriel Lippmann.

In 1886, Lippmann became interested in developing a way to fix the colors of the solar spectrum onto a photographic plate, where the image remains fixed and can remain in daylight. In 1891, he produced color images of a stained-glass window, a bowl of oranges, and a colorful parrot, as well as landscapes and portraits.

The optical image was projected onto a photographic plate. The silver halide grains on the other side of the glass plate were covered in a transparent coating. The projected light was reflected back into the emulsion after hitting a liquid mercury mirror.