The article was contributed to Space.com's expert voices: op-ed and insights.

The Associated Press national editor and state government reporter is named Stacy Morford.

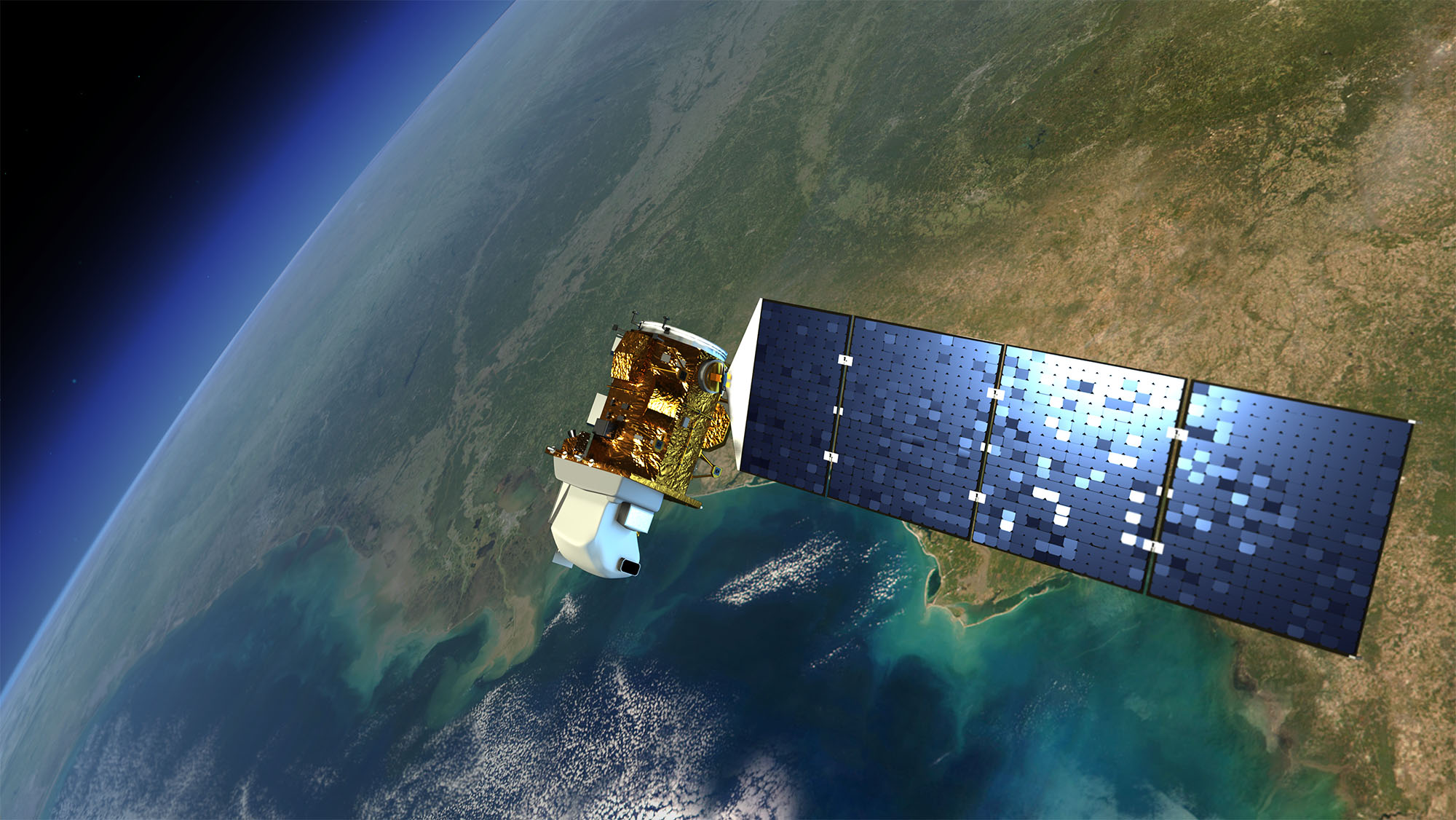

The U.S. launched a satellite 50 years ago.

It showed how humans were changing the face of the planet by burning landscapes, wiping out forests, and other ways.

The first Landsat satellite was launched in 1972 NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey are using the Landsat 8 and 9 satellites to observe the planet.

You can celebrate 50 years of Landsat with these stunning images.

The images and data from these satellites are used to find heat islands and understand the impact of new river dams, among many other things. Results can help communities respond to risks that are not obvious.

There are three examples of Landsat in action.

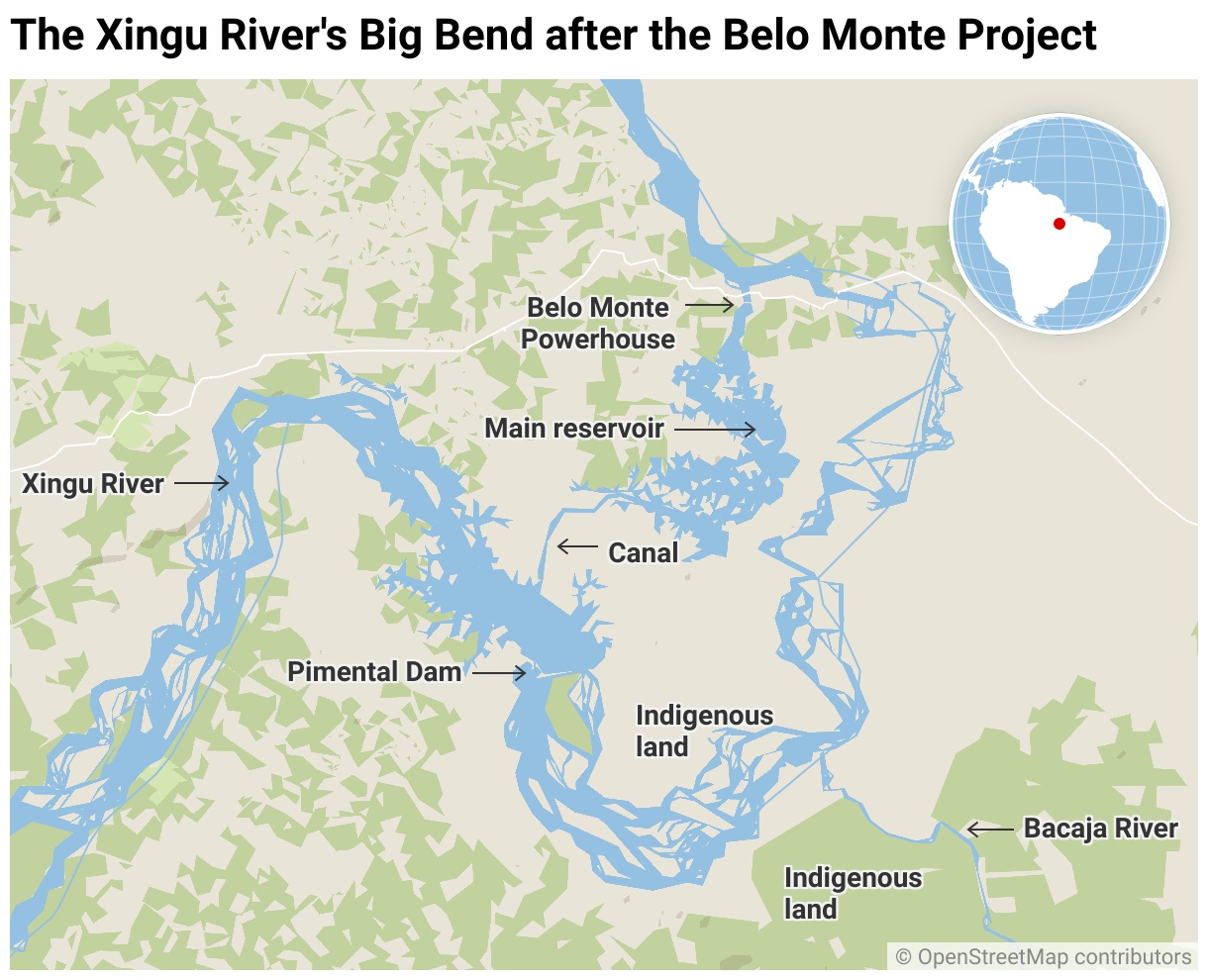

When work began on the Belo Monte Dam project in the Brazilian Amazon in 2015, Indigenous tribes began to notice a change in the river's flow. They depended on the water for food and transportation.

A new channel would allow 80% of the water to be diverted to the dam.

There was no proof that the change in water flow harmed fish according to the group that runs the dam.

From above, there is clear proof of the project's impact. The team used satellite data to show how the dam changed the hydrology of the river.

Satellite observations can be used to empower populations around the world who face threats to their resources, according to the authors.

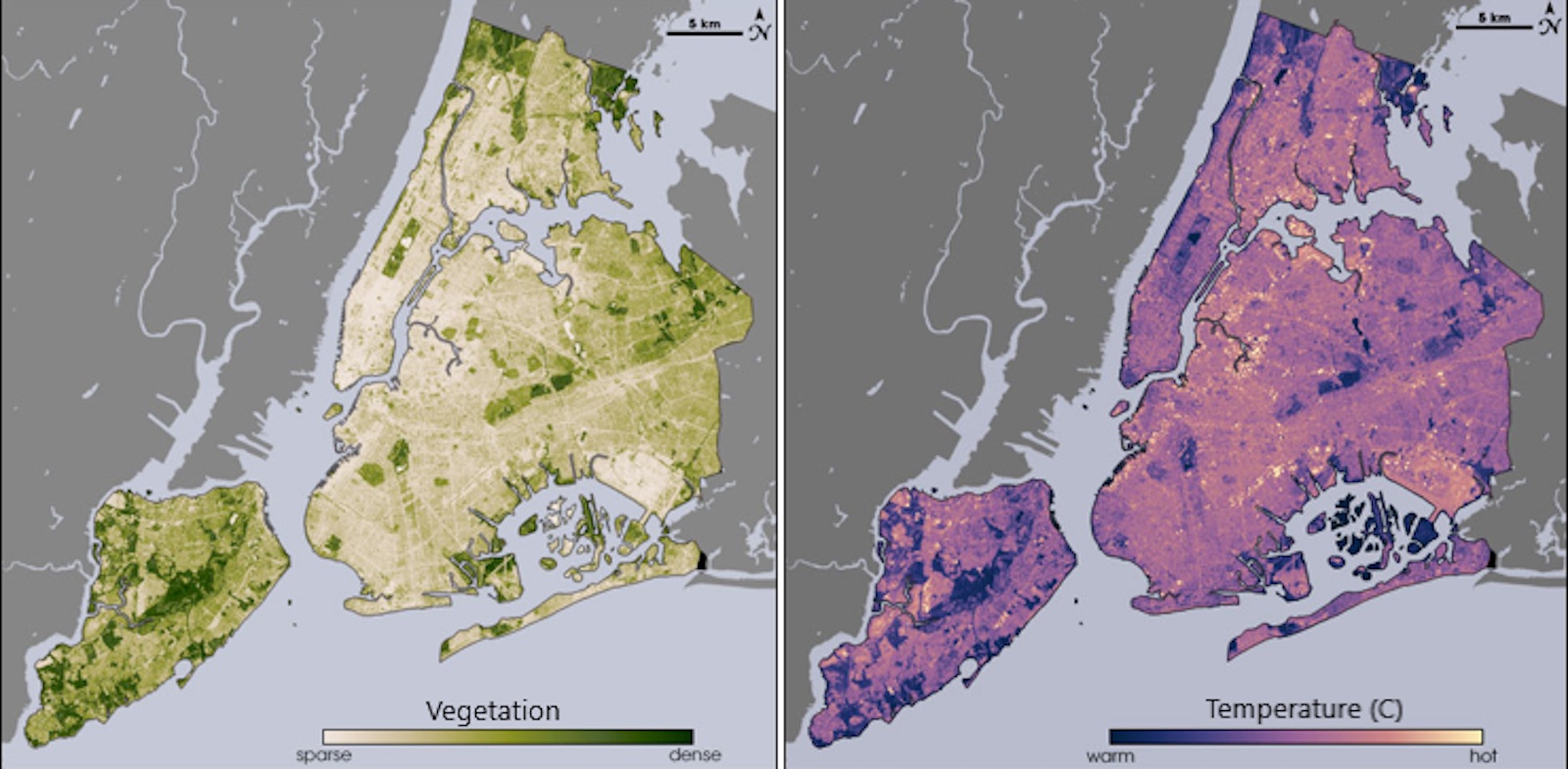

Scientists can use Landsat's instruments to map heat risk in cities as global temperatures rise.

"Cities are generally hotter than surrounding rural areas, but even within cities, some residential neighborhoods get dangerously warmer than others just a few miles away," says Daniel P. Johnson, who uses satellites to study the urban heat island effect.

Neighborhoods with more pavement and buildings can be more warm than leafier ones. He found that the hottest neighborhoods tend to be low-income, have majority Black or Hispanic residents and had been subjected to redlining.

The "micro-urban heat islands" can experience heat wave conditions before officials declare a heat emergency.

Knowing which neighborhoods face the highest risks allows cities to organize cooling centers and other programs.

Satellites can be used to spot changes in hard to reach areas. Along the U.S. Atlantic coast there are dying wetlands.

Ghost forests are landscapes of dead, bleached-white tree trunks.

Emily Ury uses Landsat data to spot changes to wetlands. She was able to confirm that they were ghost forests by using high-resolution images from the internet.

The results were very disappointing. Over the past 35 years, more than 10% of the forested wetlands in the Alligator River National Wildlife refuge have been lost. There is no other human activity on the land that is protected by the federal government.

As the planet warms and sea levels rise, the amount of salt in the soil of coastal woodlands from Maine to Florida will increase. Ury writes that rapid sea level rise seems to be out pacing the ability of these forests to adapt.

An overview of the war's effects on Ukraine's wheat crop is one of the many stories that can be found in Landsat's images. Many projects are using Landsat data to track global change and possibly find solutions to problems, such as the fires that have put Alaska on track for another historic fire season, and the fact that Landsat data can be used to track global change.

Under a Creative Commons license, this article is re-posted. The article is open in a new tab.

Become a part of the discussion and follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates on social media. The author's views do not represent those of the publisher.