The captain of theCSS Alabama described a patch of the sea as a "remarkable patch of the sea". The Alabama was one of several Confederate vessels that traveled the world's oceans during the U.S. Civil War. Captain Raphael Semmes and his crew were frightened by the sea they encountered that January night. Semmes said that he was startled when they passed from the deep blue water in which they had been sailing into a patch of water so white that it startled him.

The crew dropped a weighted line over the gunwale and it sank for 600 feet. Semmes wrote that there was a subdued glare around the horizon and a lurid, dark sky overhead. The Alabama might have been conceived to be a phantom ship because of the change in the face of nature. The Alabama traveled through the water for several hours, finally leaving the patch as quickly as it entered it.

One of the earliest reliable accounts of the sea is Semmes's firsthand description. One of the ocean's most persistent mysteries is close to being solved after combining dozens of historical reports with state-of- the-art satellite data.

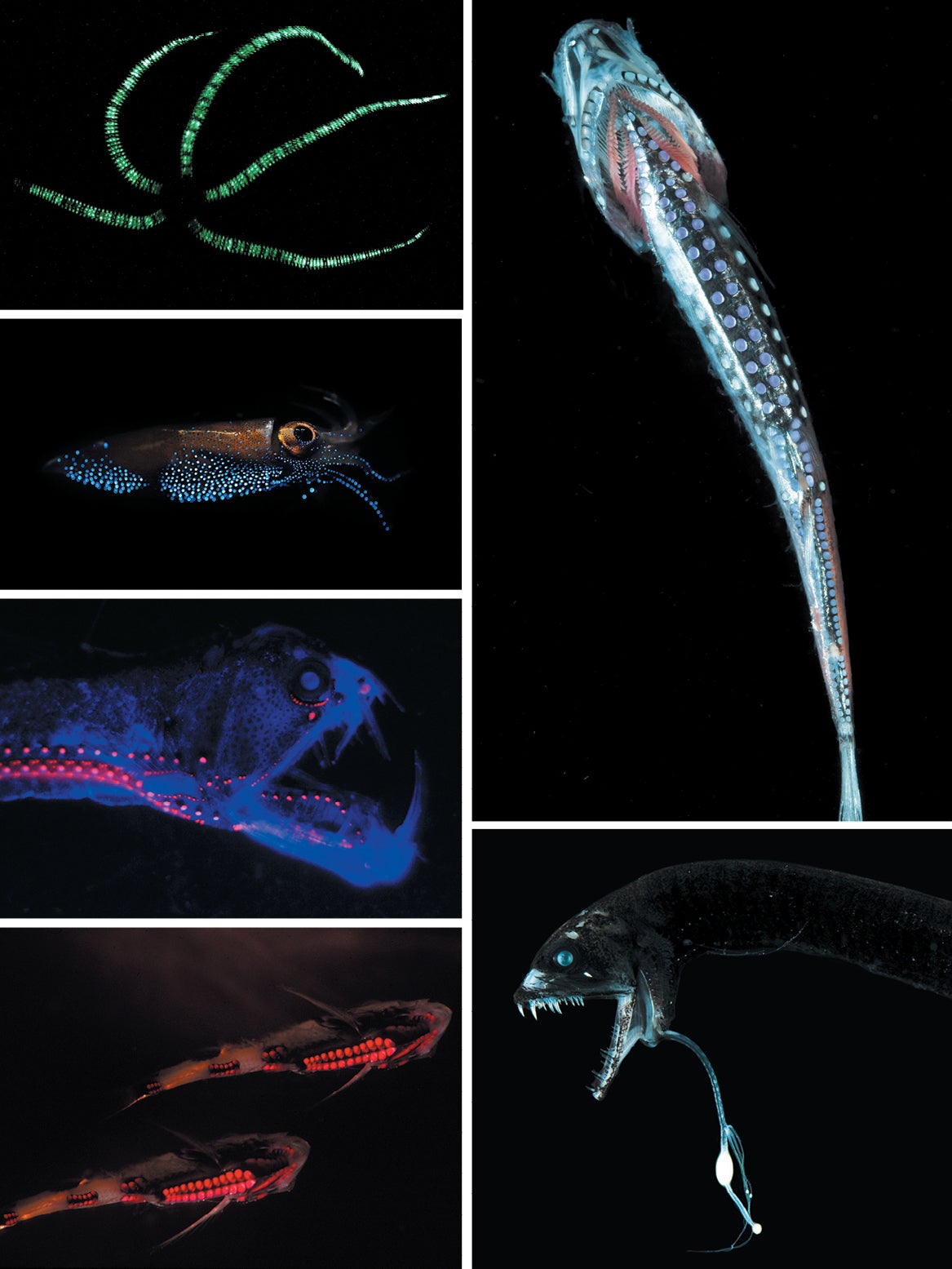

bioluminescence is the cold radiance emitted by some organisms. It is one of the oldest subjects of scientific study. Animals are mentioned in ancient poetry and songs. In the third century B.C.E., Aristotle noticed that if he struck the sea with a rod, the water would produce a bright blue flash. The Black Forest of central Europe was rumored to glow with bio-luminescent birds, but it was never proved.

In 1370, Egyptian zoologist Al- Damiri included bioluminescent insects. During his fateful approach to the Bahamas in 1492, Christopher Columbus was able to see some light in the ocean. After hundreds of years of speculation, scientists in the late 1800s confirmed that bioluminescence is a result of an oxidation reaction. No one knew what caused organisms to glow or what purpose the light might serve.

Blue-green flashes and gleams are described in most accounts of bioluminescence on land and at sea. There were reports such as that of Captain Semmes. The sailors plied the water with white light and it glowed for miles. Even though they were rare and strange, people still considered them to be tall tales. They were portrayed as bad omens by Herman Melville in his novel, "Moby-Dick." He described a mariner's dread on entering a "midnight sea of milky whiteness" as if "shoals of combed white bears were swimming round him." In Jules Verne's novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Pierre Aronnax, the fictional submarine pilot, calmly informs his assistant that the whiteness which surprises you is caused by the ocean.

It would be more than a century before science began to catch up with science fiction. A U.S. Navy research vessel encountered a sea off the Arabian Peninsula. The scientists onboard, who were conducting a broad study of marine bioluminescence, were equipped for this, and they quickly collected seawater samples for inspection. In addition to the dinoflagellates, copepods and other types of plankton, the samples contained bioluminescentbacteria. According to the researchers, the seas were created after the colonies on the water died. When the dead algal cells broke, they released the lipids that were eaten by thebacteria, which became concentrated enough to create a continuous glow.

Milky seas had been established as a biological phenomenon. Researchers needed more data to understand why they happened.

The U.S. Navy is concerned about marine bioluminescence because a patch of bright seawater can outline a submarine. Steven Miller, an atmospheric scientist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Monterey, Calif., wondered if satellites could detect bioluminescence from above. The Operational Line Scan system that flew on U.S. Air Force satellites was the only one that could see at night. Miller searched the internet for mentions of widespread bioluminescence because he knew that most surface displays of marine bioluminescence were too small to register on the sensor. William R. Corliss maintained a catalog of "unusual & unexplained" occurrences on the science frontier website.

Miller started to collect accounts from other people. A report from a British merchant ship that sailed through the Horn of Africa in 1995 was among them. The bioluminescence appeared to cover the entire sea area, from horizon to horizon, and it appeared as though the ship was sailing over a field of snow.

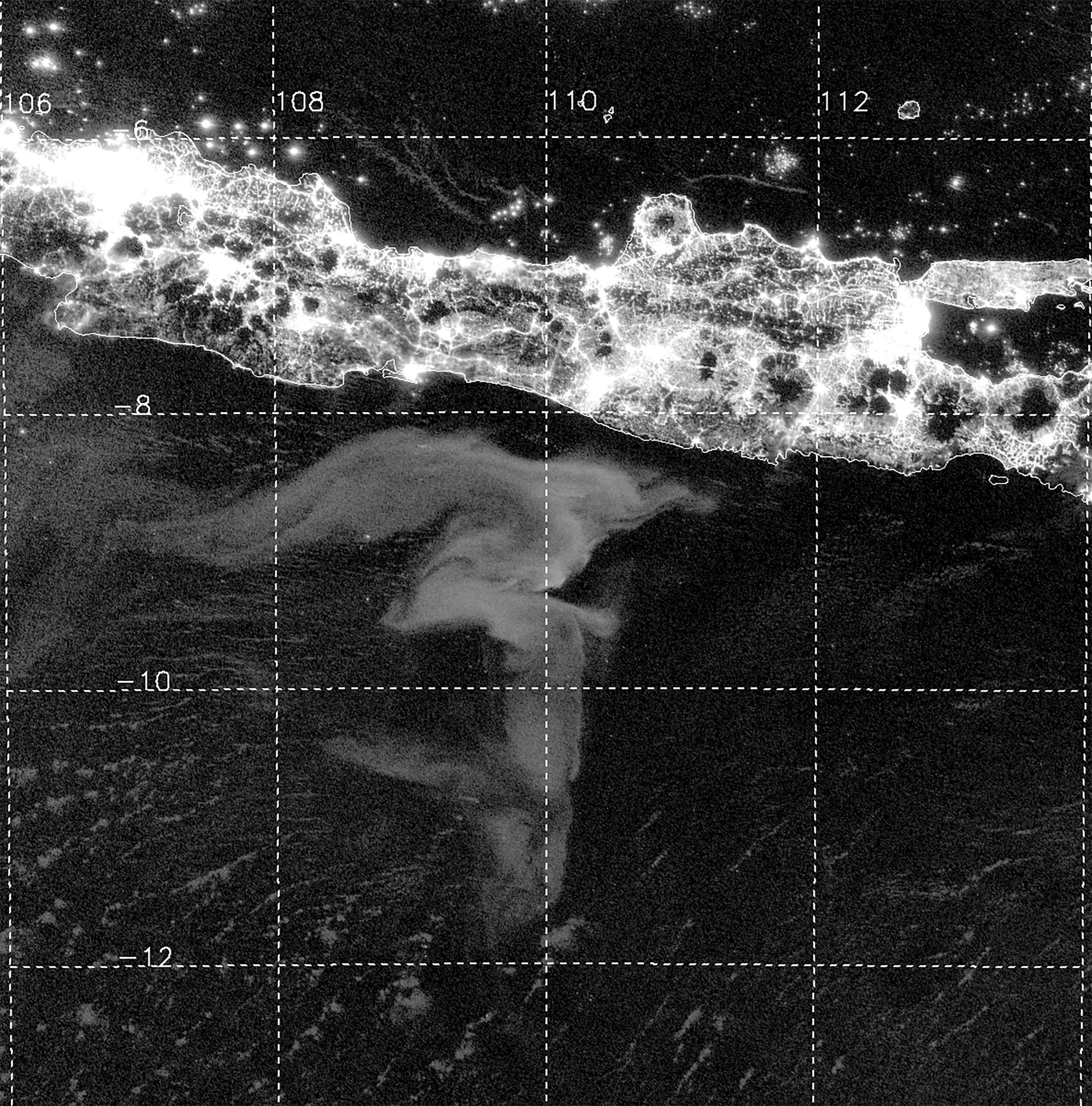

Miller initially didn't see anything when he looked at the OLS images from that day. He saw a small smudge when he went in. He remembers that it looked like a finger smudge but it moved as he moved it. The coordinates of the ship's log were found on the edges of the smudge. The smudge was found when he looked at OLS images from the days before and after the meeting. Miller thought that bioluminescence could be seen from space.

Miller reached out to Steven Haddock, a marine Biologist at the MBARI, to share his findings. One of his mentors, marine biologist Peter Herring, had cataloged hundreds of descriptions of milky seas dating back to Captain Semmes and the Alabama. He spent a lot of his career trying to get as close as possible to bioluminescent organisms using crewed or remotely operated deep-sea vessels. They started to work together.

Miller hoped a new, more sensitive low-light visible-spectrum instrument called the day-night band would allow a systematic survey of the milky way. The sensor is on two satellites more than 500 miles above Earth's surface each day. The DNB is more sensitive than the OLS. It can pick up the faint glow that comes from the absorption of ultraviolet light in the upper atmosphere. The clouds were all over the place. Miller explains that the airglow makes the veil of light diffuse. He says that it took them a long time to separate bioluminescence from these other phenomena.

The northwestern Indian Ocean, where both the Alabama and the Lima had encountered them, as well as around Indonesia, were the places where the milky seas were most often reported. Miller narrowed his search to these seasons and locations and found a dozen events that weren't clouds or airglow and were invisible during the day. An area the size of Kentucky was covered by one event that was visible for at least 45 nights. The persistence of the DNB sensor suggests that it could be used to dispatch researchers to the new seas in time to conduct dives. Miller says there's only so much you can do from space. You can't get into the water, you can't see the glow in the water, and you can't measure the chemistry of the water. You need to be in the middle of it to truly comprehend.

Miller is waiting for the chance to be in the middle of a sea. Sam Scott helped to sail a restored Dutch ketch from Malta to Singapore in the summer of 2010 Scott saw an odd glow in the air as he began his watch. He was able to see the boat's sails and hull even though the sky was completely dark. Scott and his crewmates left the sea in about four hours. It was bioluminescence of some kind, but it was on this wild, wild scale, unlike anything I'd ever seen before.

Scientists propose different hypotheses about how the seas form. The navy investigators thought that the bioluminescentbacteria they collected had congregated around the bloom. The steady glow is thought to be the result ofquorum Sense, the ability ofbacteria to communicate through chemical signaling. They maintain a constant shine once their density is high. Why? Some biologists think bioluminescence in other marine organisms helps them attract food or mates or functions as a kind of alarm, flashing when they are under attack in hopes of attracting their predator. When a colony runs low on food in the open water, it may glow to encourage nearby fish to eat thebacteria, which in turn may sustain thebacteria in their guts.

The idea that milky seas occur most often in winter and summer is complicated by the decade of DNB data. The peaks in the Indian Ocean appear to be the strongest during the winter and summer monsoons. The Indian Ocean Dipole is a pattern of cool, dry conditions and strong winds in the eastern Indian Ocean during May and October. The satellite data suggests an explanation for why the glow occasionally seems to extend to some depth, creating the perception among mariners that their ship is suddenly floating in light. He theorizes that such conditions could foster colonies that are super dense, and that this could lead to the creation of a large and deep sea.

The ability of the DNB sensors to detect milky seas will allow researchers to quickly head out to the ocean and collect samples. There are still mysteries to be solved until then.

Much bigger questions remain about the nature, function and extent of bioluminescence itself, which is why the secrets of milky seas persist. Since most bioluminescent organisms live in the ocean, observing bioluminescence firsthand has required a lot of resources. Edith Widder started her research into bioluminescence in the 1980s. In her book, below the edge of darkness, she recounts her numerous and occasionally hair-raising submersible experiences, including a life threatening leak at a depth of 350 feet. She told me that she's spent a lot of her career in submersibles because only recently have cameras been able to see both light and bioluminescence. It's breathtakingly beautiful and finally other people are going to see it.

Widder and others who have taken deep-sea voyages have known for a long time that bioluminescence is a common ability. An analysis of 17 years of video observations collected by remotely operated vehicles off the California coast was published in 2017. Martini and Haddock found that at least three quarters of the organisms were capable of bioluminescence after taking more than 350,000 observations. At different depths, the percentage remained the same. They discovered that a third of the organisms on the ocean floor are bioluminescent. The first documented case of bioluminescence in a sponge was identified by Martini, and he was not the only one.

The ocean is the largest living space on the planet and the two analyses suggest that bioluminescence is one of the main ecological features. Martini says that it is something you will never see in your life. Everything is glowing at the sea. For Martini, Haddock, Widder and the few other marine bioluminescence researchers, the pervasive glow only increases their interest in its ecological functions, evolutionary history, chemistry and genetics.

Humans have been helped by bio-luminescent species. Biologists isolated bioluminescent jellyfish in the 1960s and used green fluorescent protein to show the components of living cells. One of the most diverse estuaries in North America is the Indian River Lagoon. The lagoon has been polluted by farms and lawns as well as sewage and septic system leaks for decades. Widder and her colleagues have taken samples from the lagoon and mixed them with bioluminescentbacteria in the lab to figure out the relative concentrations of pollutants in the lagoon.

The ability of marine organisms to use their own bioluminescent capacity is under threat. The entire deep sea is expected to be impacted by the rush to mine valuable metals from the ocean floor because the water is clear enough for bioluminescent organisms to communicate with one another. The robotic mining vehicles kick up a cloud of debris. After machines pump collected material to the surface and remove the fist-sized, metal-rich nodules, they dump the remaining mud and silt back into the sea, again clouding once transparent water.

In the context of ocean ecology and ocean health, it's important to understand how widespread and widely usedbioluminescence is. If you do something that affects that process, it will have a domino effect that we can only now begin to appreciate. The glowing seas that terrified generations of sailors have left no trace, but the cloudy seas created by humans could permanently dim the ocean's light.