Jane McMullen is a news correspondent for the British Broadcasting Corporation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThirty years ago, a plan was hatched to convince the public that climate change wasn't a problem. The meeting between some of America's biggest industrial players and a PR genius was a devastatingly successful strategy that lasted for years.

E Bruce Harrison, a man widely acknowledged as the father of environmental PR, stood up in a room full of business leaders and delivered a pitch.

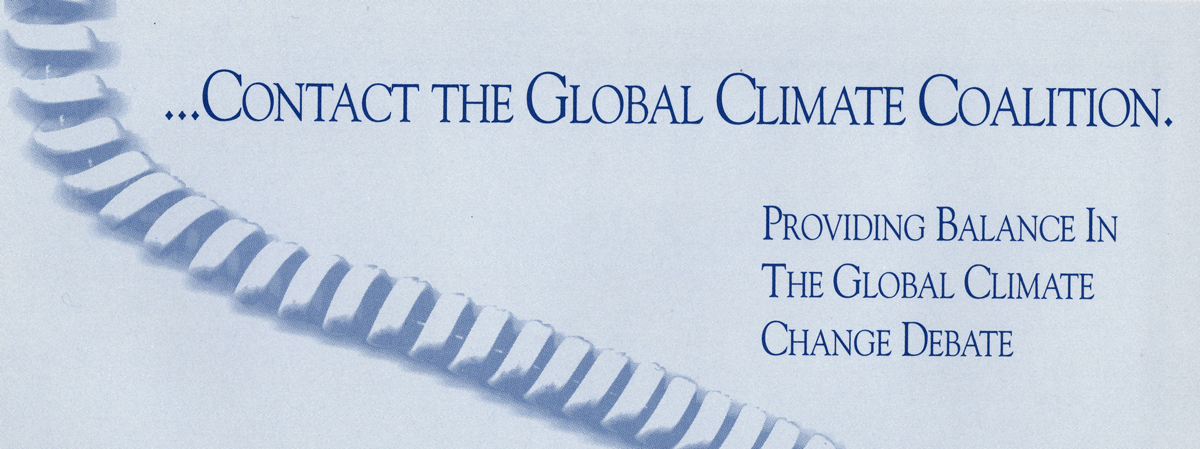

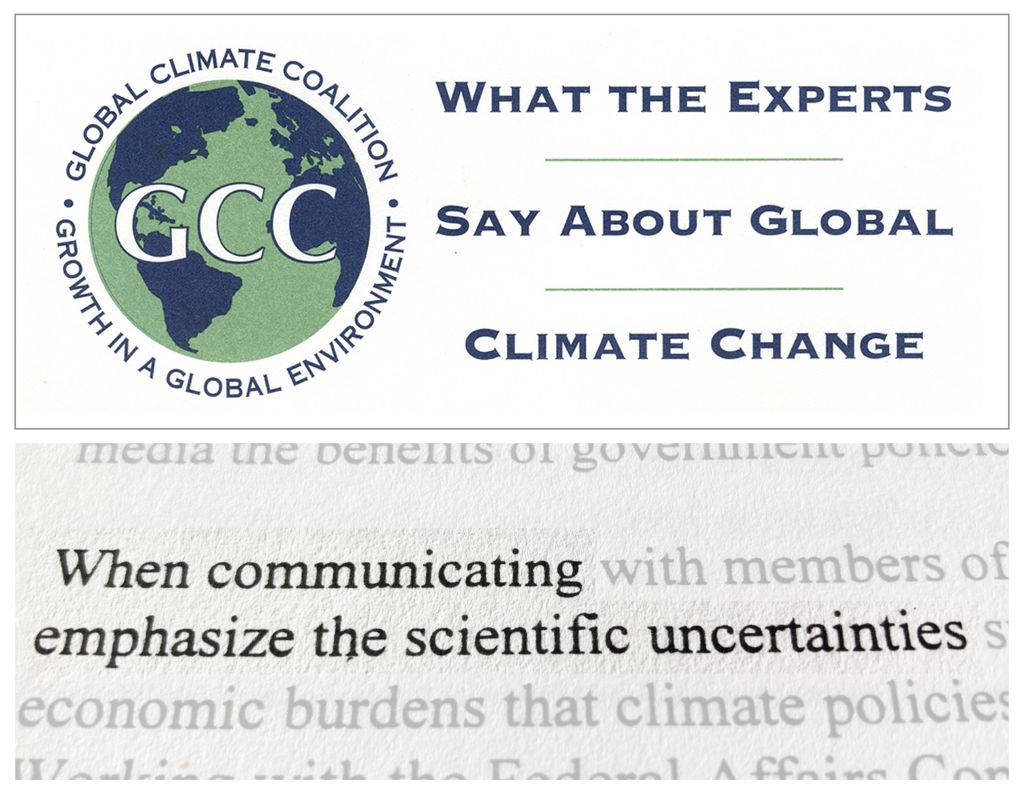

The contract was worth half a million dollars a year and needed to be signed by the end of the year. The Global Climate Coalition was looking for a communications partner to change the narrative on climate change.

Two people present that day are sharing their stories for the first time.

"Everyone wanted to get the Global Climate Coalition account, and I was in the middle of it."

Three years ago, the GCC was conceived as a forum for members to exchange information and lobby against action to limit fossil fuel emissions.

Though scientists were making rapid progress in understanding climate change, and it was growing in salience as a political issue, the Coalition didn't see much cause for alarm. In 1990, a senior lobbyist said that President George HW Bush's message on climate was theGCC's.

There would be no requirement to reduce fossil fuel use.

All that changed in 1992 The international community created a framework for climate action in June and the presidential election brought Al Gore into the White House. The new administration wanted to regulate fossil fuels.

A public relations contractor was put out for bid by the Coalition.

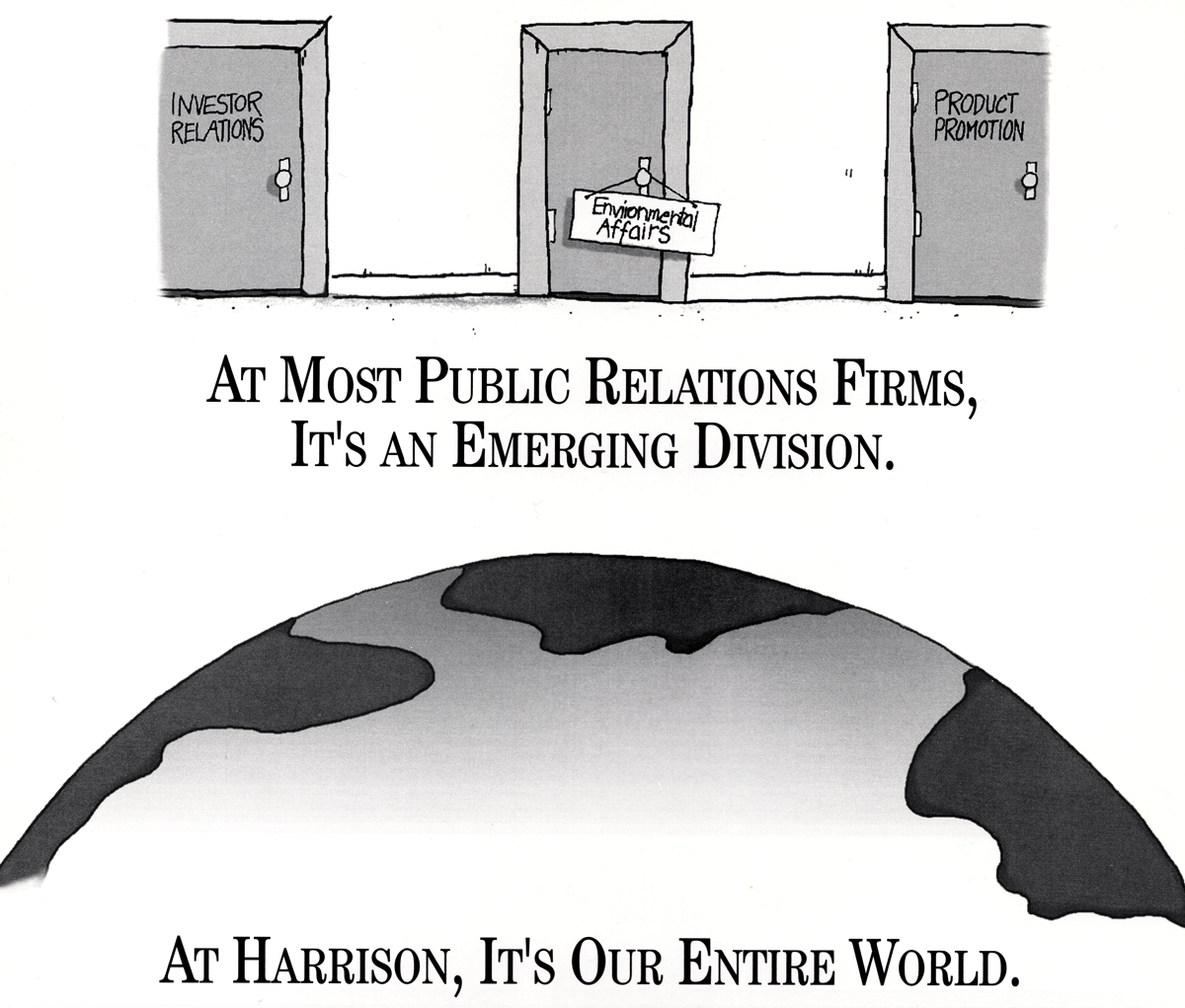

E Bruce Harrison

E Bruce HarrisonFew in the PR industry would have heard of E Bruce Harrison or his company, but he had a number of campaigns for some of the US's biggest polluters.

He had worked for the tobacco industry, the chemical industry, and the big car makers, and he had recently run a campaign against tougher emissions standards for the big car makers. One of the best firms was built by Harrison.

Harrison was interviewed by a media historian before he died.

She claims that he was a master at what he did.

Drawing on thousands of newly discovered documents, this three part film charts how the oil industry mounted a campaign to sow doubt about the science of climate change.

Harrison had assembled a team of seasoned PR professionals and almost total novices. The man had no industry credentials. Before he became an environmental journalist, he studied ecology. A chance meeting with Harrison, who must have seen the strategic value of adding Rheem's environmental and media connections to the team, led to a job offer on the Gulf Cooperation Council pitch.

One of the most pressing science policy and public policy issues that we were facing was an opportunity for me to get a front row seat.

Rheem says it felt important.

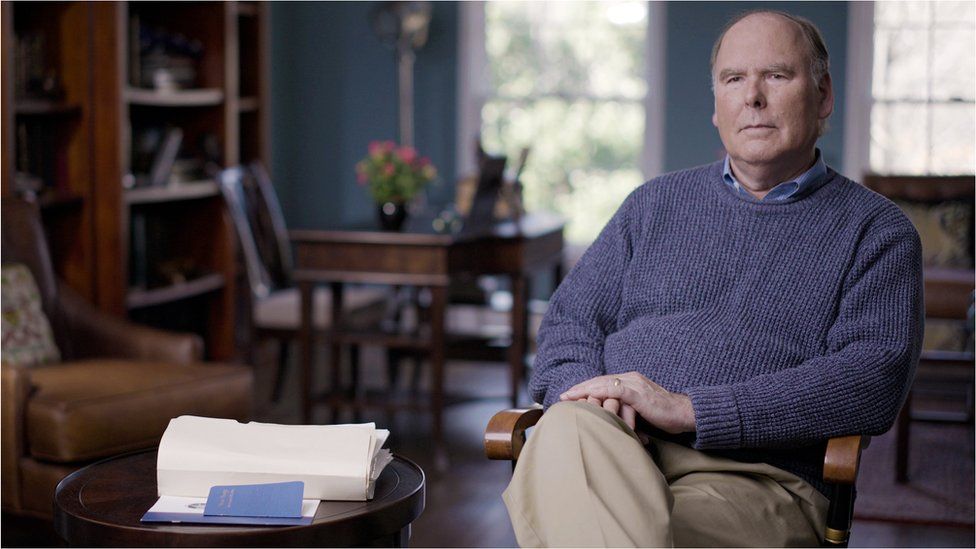

Don Rheem

Don RheemTerry Yosie, a senior vice-president at the firm, remembers that Harrison began the pitch by telling his audience that he was instrumental in fighting the auto reforms. The issue was re-framing by him.

Climate regulation would be defeated by the same tactics. The policy makers needed to consider how action on climate change would affect American jobs, trade and prices in order to convince people that the scientific facts weren't settled.

An extensive media campaign would be used to implement the strategy.

Many reporters were assigned to write stories and they were struggling with the issue. I wanted reporters to read the backgrounders so I wrote them.

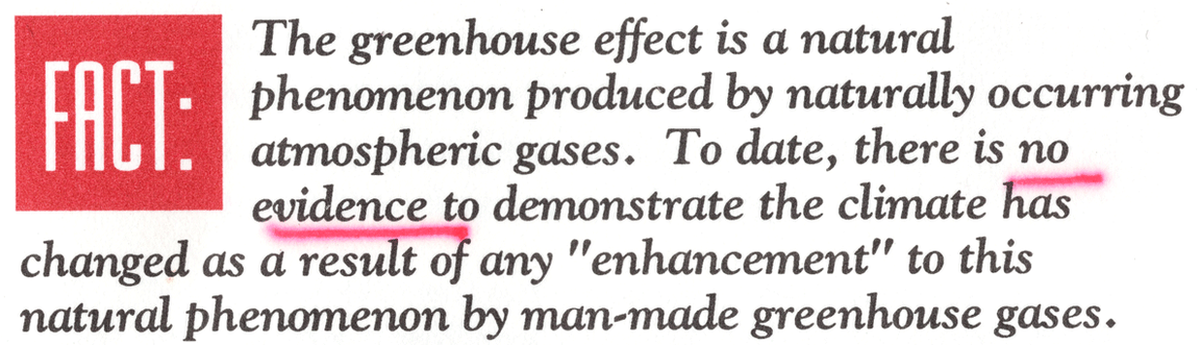

There was uncertainty in the full range of the GCC's publications.

Within a year, Harrison's firm claimed to have secured more than 500 mentions in the media.

Harrison had a meeting with the GCC in August 1993.

According to an updated internal strategy pitch, the rising awareness of the scientific uncertainty has caused some in Congress to pause on advocating new initiatives.

Over the past year, activists have conceded that they lost ground in the communications arena.

Harrison told them they needed to expand their voices.

Industry representatives have less credibility with the media and general public than noted experts.

Climate scientists agree that human-caused climate change is a real issue that needs to be addressed, but a small group disagrees. The plan was to pay these sceptics to give speeches or write op-eds and to arrange media tours so they could appear on TV and radio.

"My role was to give those voices a stage and identify the voices that weren't in the mainstream." We did not know a lot at the time. Part of my job was to highlight what we didn't know.

The media was looking for these viewpoints.

Journalists were interested in the contrarians. The appetite was already there.

If you say something enough times, people will begin to believe it

Many of the sceptics and deniers reject the idea that funding from the Gulf Cooperation Council had any impact on their views. The campaign the scientists and environmentalists were tasked with repudiating was well-organised and effective.

Environmentalists don't know what's hitting them because of the Global Climate Coalition.

The PR firms that work for the fossil fuel companies know that truth has nothing to do with who wins the argument. People will start to believe it if you say it a lot.

Harrison wrote in a document that the "GCC has successfully turned the tide on press coverage of global climate change science, effectively counteracting the eco-catastrophe message and asserting the lack of scientific consensus on global warming"

The industry's biggest campaign to date was against international efforts to negotiate emissions reductions at Kyoto in December 1997. Scientists agreed that human-caused warming was now visible. The US public was not sure. A majority of respondents believed scientists were divided. It was difficult for politicians to fight for action because of public antipathy. It was a big win for the coalition.

E Bruce Harrison was proud of what he did. Aronczyk says that he knew how important he was to moving the needle on how companies were involved in the discussion about global warming.

I think it's the moral equivalent of a war crime

Harrison sold his firm the year after the Kyoto negotiations. Yosie moved on to other environmental projects after Rheem decided public relations was not the right career for her. As some members became uneasy with its hard line, the GCC began to fall apart. The tactics, the playbook, and the message of doubt were now embedded and would live on. The consequences are inescapable three decades on.

The big oil companies are trying to block action, says former US Vice- President Al Gore.

It is the most serious crime of the post-World War Two era. The consequences of what they've done are beyond imagination.

Is it possible that I would do something differently? It's a hard question to answer, according to Don Rheem, who was in charge of the operations. Not much has happened, there's some sadness.

He believes that China and Russia have been responsible for the decades of climate inaction, rather than American industry, because climate science was too uncertain in the 1990s.

It is easy to create a conspiracy theory about the intent of the industry to stop progress. I didn't think that was true.

I was young at that time. I was interested. Is it possible that I would have done things differently now?