As American settlers pushed west into the Great Plains, stories began to emerge of depressed, anxious, and even violent people. There is evidence that there was a rise in cases of mental illness in the Great Plains in the late 19th century. There is an alarming amount of insanity among farmers and their wives in the new prairie states.

The isolation and bleak conditions of this time and place are often blamed on prairie madness. The sounds of the prairie are mentioned a lot. During winter, the silence of death rests on the landscape. There is a character in the story who hates the wind with its evil spite and hisses and jeers when he tries to use it to his advantage.

Alex D. Velez, a paleoanthropologist who studies the evolution of human hearing, wondered if there was any truth to this idea. According to a new paper by Velez, the eerie sound of the wind and silence could have contributed to mental illness in settlers. It isn't much of a leap that research shows that what we hear can make us more prone to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Velez wanted to know if there was something special about the sound of the prairie. Velez was able to get more recent recordings from the plains in Nebraska and Kansas, which captured sounds like the wind and rain, as well as the din of traffic in urban areas. He created visual representations of the sound frequencies in the recordings and compared them to a map of sound frequencies that the human ear can pick up.

Velez found that the sounds of the city were more diverse, spreading across the range of human hearing and making white noise. There wasn't a lot of that background noise out on the prairie. The brain notices a sensitive part of the hearing range when it hears certain sounds.

It is very quiet until suddenly, the noise that you do hear, you can't hear anything else.

Imagine how bad it would be for a newly arrived settlers to find every chicken cluck that breaks the prairie silence to be as distinct as a frog's croak or a raindrop.

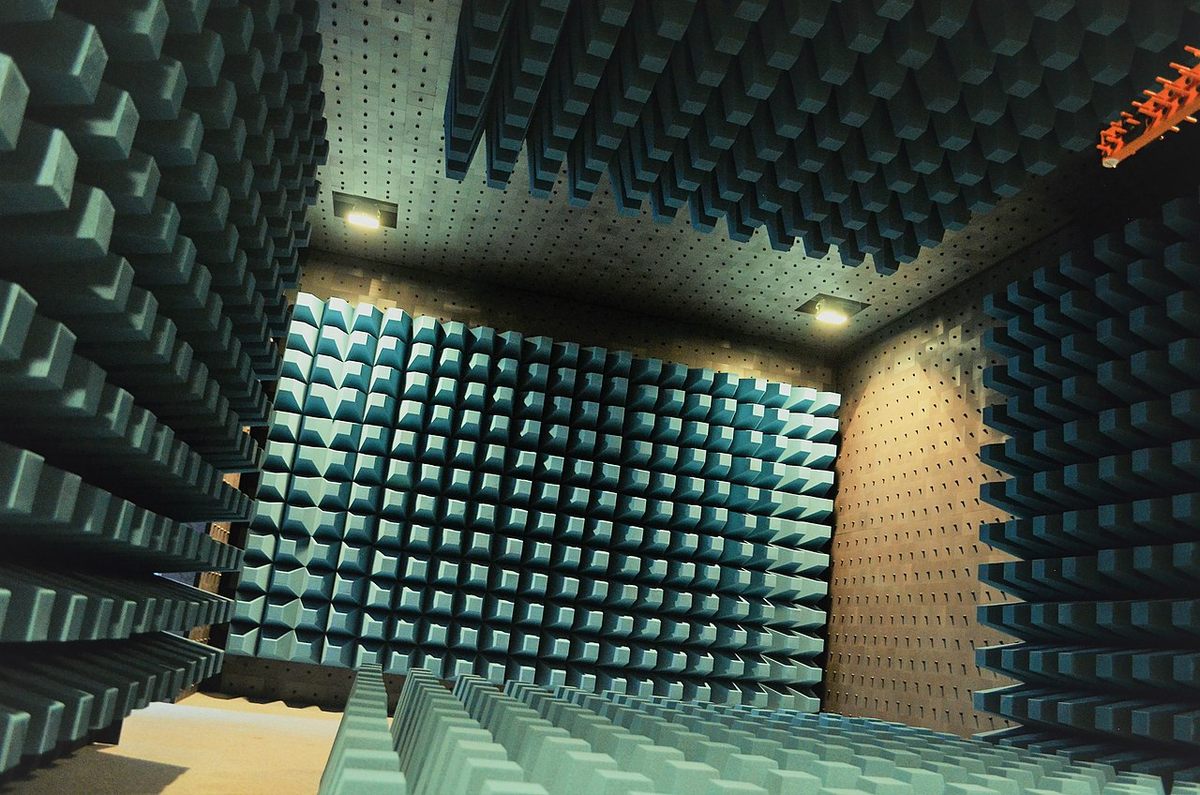

Adrian KC Lee, an auditory brain scientist at the University of Washington who was not involved in Velez's study, reminded him of sensory deprivation or being in an anechoic chamber. Even the smallest sound can become impossible to ignore in those cases. The human brain will adapt to its environment and turn up or down the volume in order to better distinguish what is happening.

Lee says adaptive is for survival It's going to give you trouble if you adapt to a very low sound environment.

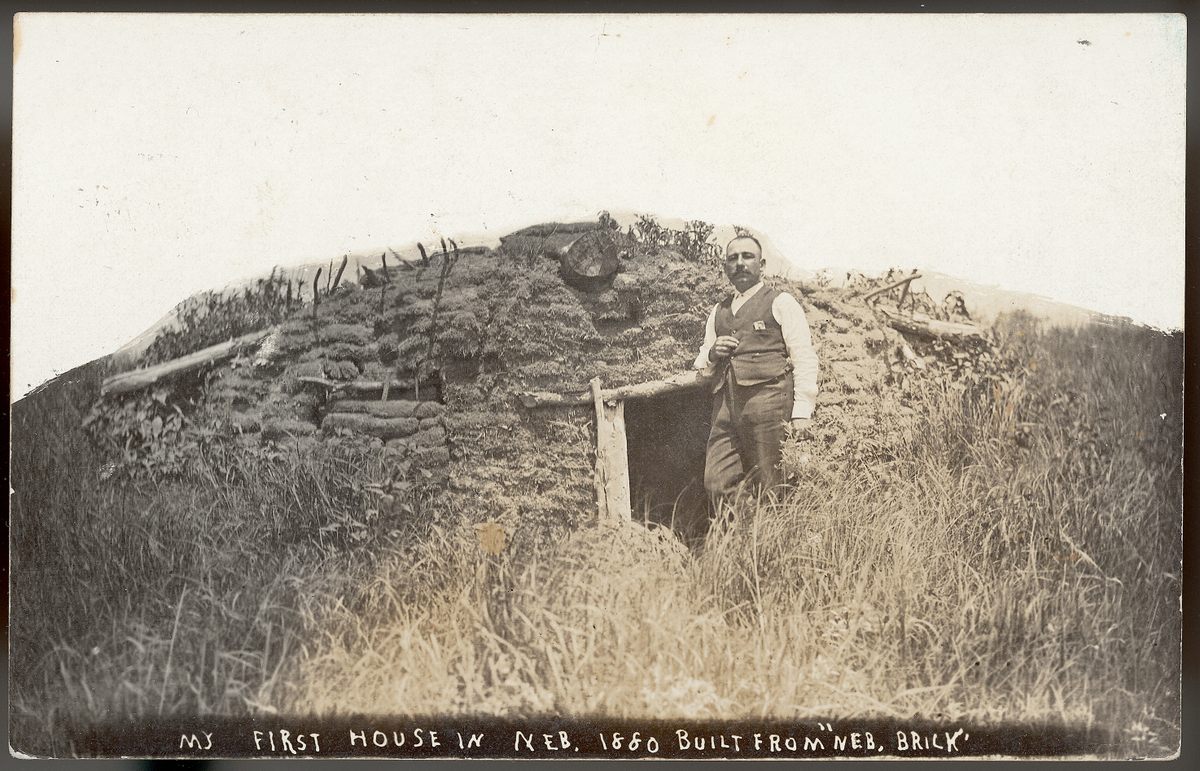

Jacob Friefeld is a research historian at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum and he wrote extensively on the Homestead Act, one of the great drivers of westward expansion. He notes that the recordings Velez used may be missing some sounds early settlers would have heard, like the howl of wolves or the roar of millions of American bison. If settlers lived in sod houses or dugouts, they might have been treated to the sound of insects and other creatures living in the dirt walls.

It is very difficult to study the symptoms of mental illness in a group of people who lived over 100 years ago. The specific language used for conditions can change, records can be inconsistent, and diagnoses can be affected by societal attitudes.

It's not easy to figure out how much of an episode of depression came from the noise and how much was a reaction to the stress. Once out in the plains people were often miles away from their neighbors. The transition may have been difficult for women, who were often forced to stay at home, limiting their opportunities for stimulation and socializing. Some people were stressed due to the fear of freezing, crop failure, and monetary ruin inherent in homesteading.

Velez's work can't prove how much prairie madness really affected settlers, but it did give him an answer to the question that captured his imagination: there may indeed be something in the sound of the plains.

It is a reminder that sounds have the power to change our lives. Many scientists are wondering if the changing sound of the Pandemic had an effect on physical and mental well-being.

The thin atmosphere of Mars does not allow sounds to travel as far as they do on Earth. Will settlers curse the silence when they get to Mars if the prairie leads to anxiety and depression for some?