Ten years ago, Peter Higgs learned that a particle named after him had been discovered. He was eating in Sicily. Outside, the stone streets of Erice burned in the midday sun; inside, a Dutch film crew was making a documentary about the boson he had described in a two-page research paper nearly 50 years ago. Alan Walker was a kind of personal assistant to the physicist who died.

Walker left the table to make a call. He quietly told John Ellis that it was him when he came back. He was urging them to attend the event in Switzerland. We should leave if John Ellis says that. On July 4, 2012 scientists working on the collider's massive detectors reported the discovery of a particle that is ten thousandth of a second to cross a single atom.

Frank Close wrote that knowledge about the fundamental nature of the universe would be there for as long as humans were alive. The ability of equations written on pieces of paper to know nature was confirmed once more.

On the morning he was awarded the Nobel prize, Higgs, who has never owned a mobile phone, disappeared again

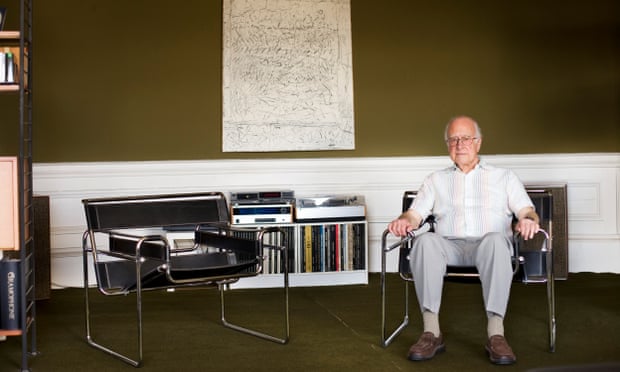

The crowd applauded and cheered. The man whose work had been so spectacularly affirmed sank into his chair and refused to answer any questions from reporters. The day after he won the prize in physics, he vanished again. He went to a seafood bar in Leith, a couple of miles away from his home, and drank a beer while the committee tried to reach him. The discoveryruined my life. He told Close that he didn't like the publicity. I like to work in isolation and have bright ideas.

Close seems to have failed despite his efforts. Close admits that his book, aptly named Elusive, became not so much a biography of the man but of the boson named after him. One of the most important stories in modern physics is the tale of the conception and discovery of the Higgs boson, a tiny tremor in an energy field that affects the entire universe. Without the Higgs there would be no atoms, people, planets, or stars. Close, a particle physicist who has served as head of communications and public education at Cern, is an excellent guide to the science of that story, as well as what we do know about the man himself.

Tom and Gertrude's only child was born on May 29, 1929, in the city of Tyneside. He was put in a class with children two years older than him because of his illness, but he was so well taught by his mother that he started school a little later than his peers. His health problems, isolation from other children and his precociousness would help mold him into a lifelong solitary person.

The same school that Paul Dirac attended when he was a student is where the family moved to in 1941. The teacher taught physics to both of them. He didn't apply to Oxford or Cambridge because of his father's view that the children of the rich went to waste their time. He wanted to study theoretical physics but was told that the research on elementary particles was over and that he should focus on his PhD. The lab of X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin was four doors down from his office. He began work in quantum field theory when he moved to Edinburgh in 1955. He spent the rest of his career in the Scottish capital after returning from London.

Howard Markel wrote a review about science and sexism.

The theory of superconductors is the beginning of the history of the particle physics. Physicists showed how electrons can come together. Currents can flow through the superconductor without resistance because of the Cooper pairs nudging each other. One consequence of this is that the interaction between Cooper pairs creates a field of light which has no mass at all.

Close documents how these insights led to the idea that elementary particles such as quarks can acquire mass. Two breakthrough papers were written in 1964. Three weeks is a long time for work. He said that the labour was small and that he was staggered by the consequences. He found out that at least five other scientists had reached the same conclusion. Franois Englert shared the prize with him. In a single sentence, he mentioned that his mass-giving field implied the existence of a giant boson and, in a third paper, to determine how that would decay into lighter particles. The decades-long quest began when this latter achievement provided a kind of fingerprints that experimenters could look for.

He didn't do any more work to develop his theory after the 1960s. He told Close that he was a bystander. He focused on the campaign for nuclear disarmament. He met his wife at a CND meeting in 1960, but they separated 12 years later.

The Standard Model is the best description of the universe. The lack of a clear goal has left scientists rudderless. The Standard Model can't be the final word for physicists. The nature of invisible "dark matter" is thought to account for most of the matter in the universe.

What are you going to do next? The Standard Model predicts that there will be an exciting new physics at the end of the 20th century, but it may be a deviation from that. There is a chance that the discovery set in train by the elusive Mr Higgs will not be surpassed for a long time.

Frank Close wrote Elusive: How Peter Higgs solved the mystery of mass. You can order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. There may be delivery charges.