A group of human genes have been found to protect older adults against cognitive decline and dementia. They focused on one of these genes and tried to figure out when and why it appeared in the human genome. The existence of grandparents in human society may have been inadvertently supported by the emergence of this gene variant, due to the influence of infectious pathogens.

The biology of most animals is designed for reproduction and not for long-term health and longevity. Humans are the only species known to live past the age of 50. Older women provide important support in raising human infants and children, who require more care than the young of other species. Scientists are trying to understand how long-term health can be achieved.

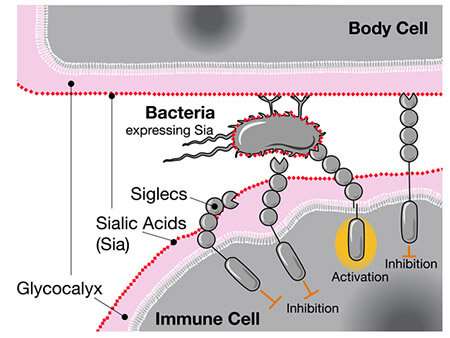

When researchers compared the genomes of humans and Chimpanzees, they discovered that humans have a different version of the CD33 gene. Human cells have a type of sugar called sialic acid. The immune cell does not attack the sialic acid when it senses it via CD33 because it recognizes the other cell as part of the body.

The CD33 is expressed in brain immune cells that help control inflammation. Damage to brain cells and amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer's disease can be cleared with the help of the microglia. By binding to the sialic acids on these cells and plaques, regular CD33receptors actually suppress this important microglial function and increase the risk of dementia.

The new variant is here. The human picked up another form of CD33 that was missing the sugar-binding site. The damaged cells and plaques can be broken down by the microglia. Higher levels of this variant were found to be protective against Alzheimer's.

In trying to understand when this gene variant first emerged, co-senior author Ajit Varki, MD, distinguished professor of Medicine and Cellular andMolecular Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and colleagues found evidence of strong positive selection, suggesting something was driving the genes to evolve more rapidly than Neanderthals and Denisovans, our closest evolutionary relatives, did not have this version of CD33 in their genomes.

"For most genes that are different in humans and Chimpanzees, Neanderthals usually have the same version as the humans," said Varki. The wisdom and care of healthy grandparents may have been an important evolutionary advantage for us.

Varki and Gagneux are both professors at the UC San Diego School of Medicine. The study supports the grandma hypothesis, according to the authors.

Evolutionary theory says reproductive success is the main driver of genetics. The prevalence of this form of CD33 was pushed by something.

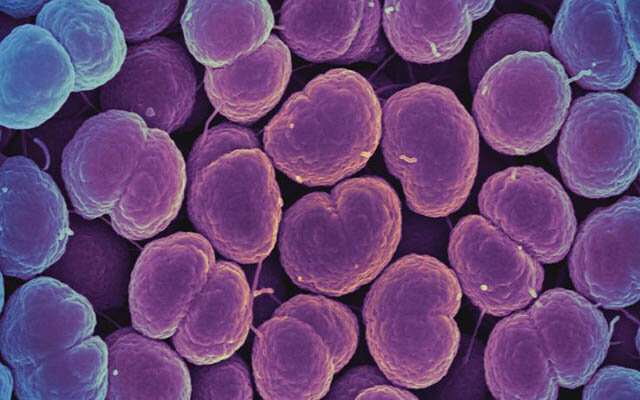

The authors suggest that infectious diseases like gonorrhea could have an impact on human evolution. CD33receptors bind to sugars that gonorrheabacteria coat themselves in. Like a wolf in sheep's clothing, thebacteria are able to trick the immune cells of humans.

The human adaptation to CD33 without a sugar binding site was suggested by the researchers. They confirmed that one of the human-specific mutations was able to eliminate the interaction between the CD33 and the bacteria, which would allow immune cells to attack the bacteria again.

The authors believe that humans initially passed on the mutated form of CD33 to protect against gonorrhea during reproductive age, and that this variant was later co-opted by the brain for its Alzheimer's benefits.

According to Gagneux, it is possible that CD33 is one of many genes selected for their survival advantages against infectious pathogens early in life, but that are then secondarily selected for their protective effects against dementia and other aging-related diseases.

There are co-authors at UC San Diego and UC Davis.

More information: Sudeshna Saha et al, Evolution of Human-specific Alleles Protecting Cognitive Function of Grandmothers, Molecular Biology and Evolution (2022). DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msac151 Journal information: Molecular Biology and Evolution