Astronomers at MIT have detected a strange and persistent radio signal from a far-off galaxy.

A fast radio burst is an intensely strong burst of radio waves of unknown astrophysical origin that usually lasts for a few milliseconds. The new signal lasts for up to three seconds more than the average. The team was able to detect radio waves that repeat every 0.2 seconds in a pattern similar to a beating heart.

The clearest periodic pattern has been detected to date, and the researchers have labeled the signal FRB 2019.1221 A.

Several billion light-years from Earth is where the signal came from. Astronomers think that the signal could come from a radio pulsar or a magnetar, two types of stars that are extremely dense and spin quickly.

There aren't many things in the universe that emit periodic signals. Radio pulsars and magnetars, which produce a beamed emission similar to a lighthouse, are examples of things we know of in our own universe. The signal could be a magnetar or a pulsar.

The team hopes to find more signals from this source and use them as a clock. The rate at which the universe is expanding could be measured using the frequencies of the bursts and how they change.

The discovery is reported today in the journal Nature, and was led by Michilli and co-authored by Calvin Leung, Juan Mena-Parra, and Kiyoshi Masui.

" boom, boom, boom"

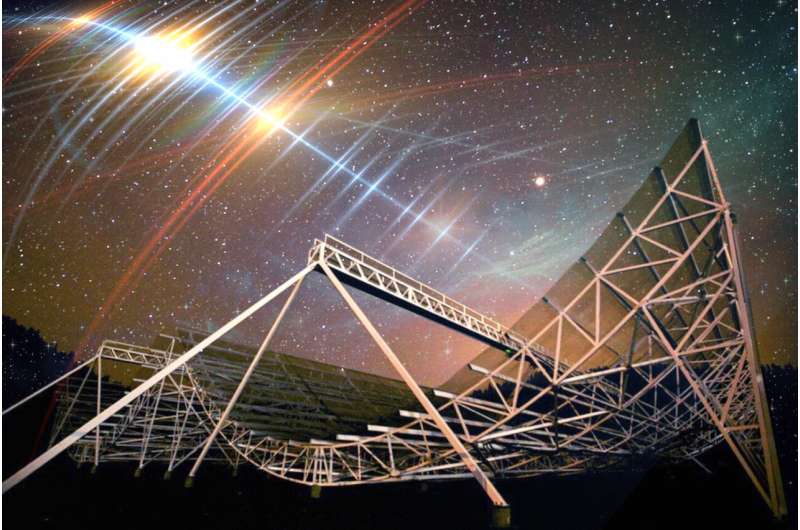

Since the first FRB was discovered in 2007, hundreds of similar radio flashes have been detected across the universe, most recently by the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment.

As the Earth rotates, Chime continuously observes the sky and picks up radio waves from the earliest stages of the universe. The telescope is sensitive to fast radio bursts and has detected hundreds of them.

Ultra bright bursts of radio waves that last for a few milliseconds are the majority of FRBs. The first periodic FRB emits a pattern of radio waves. The signal consisted of a four day window of random bursts. The 16-day cycle showed a periodic pattern of activity, but the signal of the actual radio bursts was random.

Michilli was looking at the incoming data when he noticed a signal of a possible FRB.

He says it was unusual. There were periodic peaks that were remarkably precise, emitting every fraction of a second, like a heartbeat. The signal is periodic for the first time.

There were brilliant spurts.

Michilli and his colleagues found similarities between emissions from radio pulsars and magnetars in our own galaxy after analyzing the pattern of FRB 2019.1221A's radio burst. Radio pulsars emit beams of radio waves that appear to pulse as the star rotates, while a similar emission is produced by magnetars.

The new signal appears to be more than a million times brighter than the old one. In a rare three-second window, Chime was able to catch a train of brilliant bursts that may have come from a distant radio pulsar.

Many FRBs have different properties according to Michilli. Some live in clouds that are very turbulent, while others are in clean environments. We can say from the properties of this new signal that there is a cloud of plasma around this source.

The astronomer hopes to catch more bursts from the periodic FRB 20191221A, which can help to refine their understanding of its source.

"This detection raises the question of what could cause this extreme signal that we haven't seen before, and how can we use this signal to study the universe," Michilli says. Future telescopes will be able to find thousands of periodic signals a month, and at that point we may find many more of them.

More information: Daniele Michilli, Sub-second periodicity in a fast radio burst, Nature (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04841-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04841-8 Journal information: Nature