The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. The case has the potential to change the relationship between the state legislature and state courts. The path for election subversion could be provided by it.

The issue presented in this case has been going on for a long time. The power to set certain rules is given to the states in two parts of the Constitution. The use of the term legislature to encompass a state's legislative process has long been understood by the Supreme Court. In Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission v. Arizona Legislature, the Supreme Court held that the voters in Arizona could use the initiative process to create an independent commission to draw congressional districts. Legislation was passed via initiative as part of the legislative process, according to the majority.

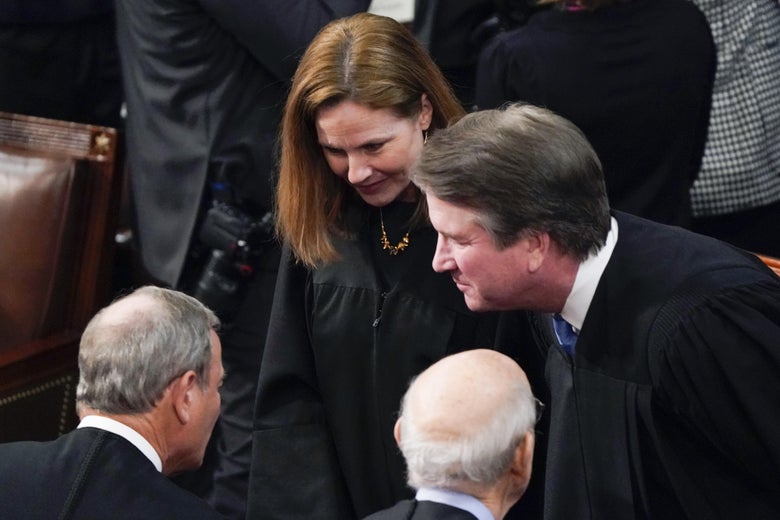

There was a strong dissent by Chief Justice John Roberts who believed that the legislature could not be removed from the process. The majority of the justices are no longer on the court.

In the independent state legislature theory, the legislature is not a part of the general structure of state government.

The facts of the case should be taken into account. The right to vote in North Carolina is protected by a provision of the state constitution, which the Supreme Court found to be unconstitutional. The North Carolina General Assembly is majority Republican. The Republican legislature argued that the holding made it impossible for them to choose the way to draw congressional districts.

There is a theory that the state constitution is not a limit on legislative power. The position would make it impossible to develop laws that protect voters more broadly than the federal Constitution. It goes against what Roberts wrote for the conservative majority of the court when he said that provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts. The courts have a role to play when it comes to drawing districts.

Our conclusion does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering. Nor does our conclusion condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void. The States, for example, are actively addressing the issue on a number of fronts. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Florida struck down that State’s congressional districting plan as a violation of the Fair Districts Amendment to the Florida Constitution.

In North Carolina, a state supreme court made a decision about what a state constitution allowed in terms of districting. The Supreme Court's composition has changed over time.

This theory could also be used to restrain state and local agencies from implementing rules for running elections.

This kind of argument shows how the ISL theory can be used to foment election subversion. How do I know? If a state court interprets state rules to allow for the counting of certain ballots, it will favor one candidate. The results need to flip if the leaders of the legislature are from the other party. The argument that Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas accepted in the 2000 Bush v. Gore case ended the 2000 presidential election and handed it to Bush.

When things don't go your way, you can't raise arguments like laches.

This was the theory that Trump allies tried to raise after the Pennsylvania Supreme Court extended the time to receive Absentee ballots in the 2020 elections because of the COVID epidemic. Justice Samuel Alito put the counting of such ballots on hold after Trump allies argued that the legislature had overstepped its bounds. The 80,000-vote win of Biden in the state was far less than the 10,000 such ballots. A radical reading of ISL could have led to a different result.

There are more limited ways of reading the ISL theory, for example when a state court or agency decision very strongly deviates from legislative language about how to run federal elections

The North Carolina legislature can lose under a strong version of the ISL theory.

An even stronger reason for believing that the North Carolina argument is weak in this case is that it was the state legislature itself that proposed the provision in the 1970 constitution guaranteeing these voting rights for North Carolina voters, which have now been interpreted by the state supreme court to ban partisan gerrymandering. As North Carolina elections guru Gerry Cohen explained, “Unlike the North Carolina Constitutions of 1776 and 1868 which were promulgated by independent conventions, the 1970 state constitution was enacted by the General Assembly.” How can the state supreme court have usurped the legislature’s power when the legislature itself brought this provision into the state constitution, knowing full well that the state constitution is interpreted by the state Supreme Court?

There are strong originalist arguments that might convince some justices not to read these provisions in such a way.

Buckle up. The balance of power in setting election rules in the states could be altered by an extreme decision.

The original version of this post was posted on the Election Law blog.