Climate change is entwined with lifestyle and needs collective action to be solved. The scientific community is having a hard time engaging with people interested in making lifestyle changes to mitigate the effects of climate change due to fake news. Socially effective methods to engage and persuade the majority of the public are necessary because of the diversity of fake news on other scientific topics.

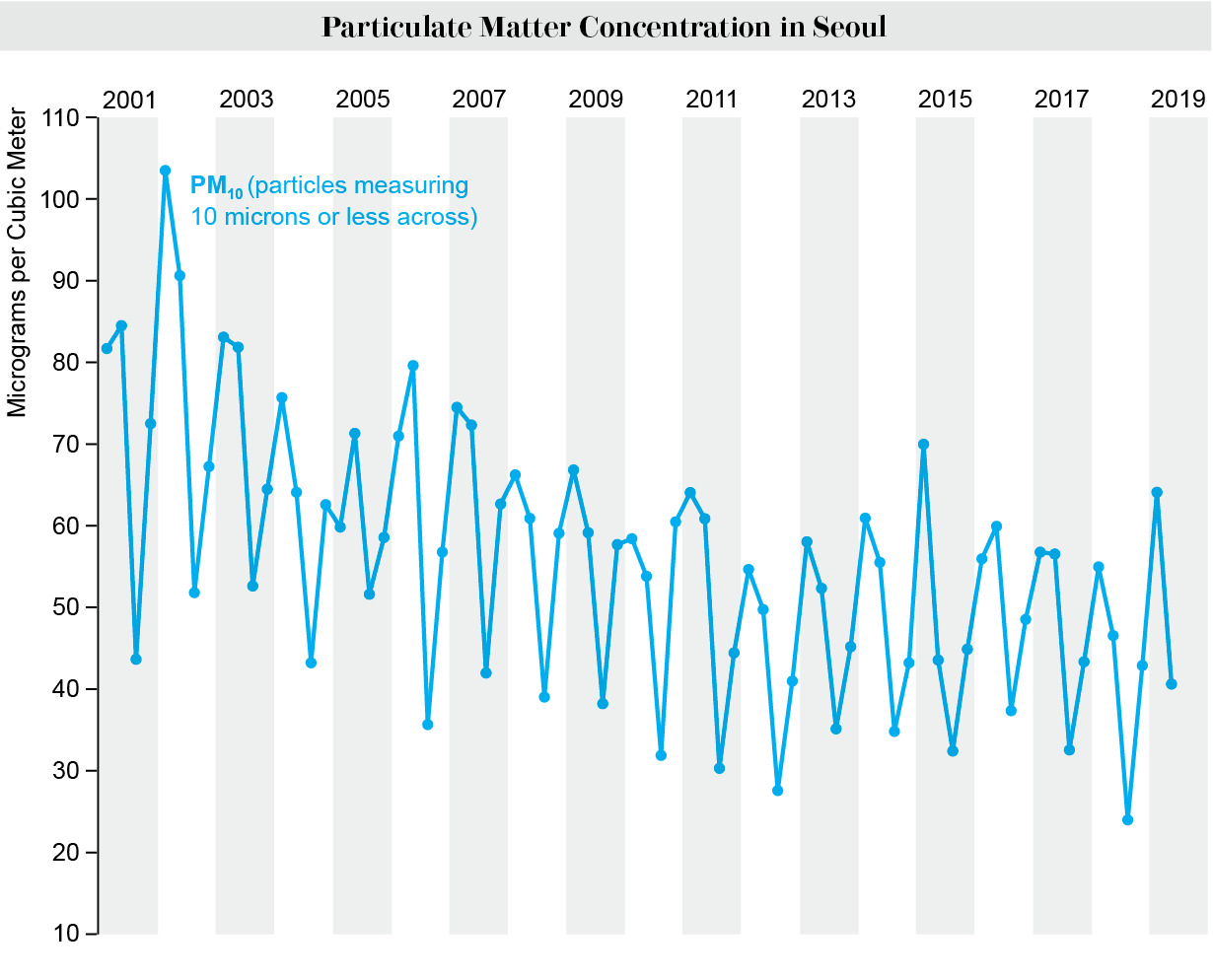

The case of air quality in Korea can show how the scientific community can act. Air quality in Korea has improved over the past two decades, but public perception is different. The people think the air quality has gotten worse. The concentration of fine dust, called PM 10, which is 10 micrometers or smaller, has actually decreased over time. Scientists can use psychology behind the gap in reality and perception to fight misinformation.

According to data from the National Institute of Environmental Research (NIER) and NASA, 52 percent of the fine dust at Olympic Park in Seoul comes from South Korean domestic factories, while only 34 come from China.

People think that most of the fine dust pollution comes from China and that it blows into Korea during the winter. The analysis shows that basic terms used in the comments on Korean news articles on Naver.com from January 2000 to February 2021.

The gap is attributed to two factors. Collective unconscious is a result of our ancestors and evolution. The public as a whole forms a common conception of unconsciousness and reacts to a particular phenomenon. The perception that the contribution from China is more than that of South Korea is perpetuated by shared information bias.

We analyzed an event that took place in November of last year. There were high concentrations of ultrafine dust that actually came from China. During the weeks of the haze, it looked like it had cloudy weather. The public perception was that China was to blame for the bad air quality. During that event, the public began to associate fine dust with China. The number of news articles on fine dust that contain the phrase "China" began to increase in November of last year, and so did the number of comments on the articles that referred to "China".

The public opinion seems to have been reinforced by the sharing of information. After the pollution event, public sentiment towards China worsened. News articles and comments on fine dust with references to China increased from late 2015 to mid 2019.

China and Japan had relatively little change in their relationship. The news articles in Japan did not blame China but focused on technical aspects of responding to the fine dust. The Chinese articles focused on local regulations and air quality degradation, with words such as "development," "construction," "control" and "pollution" often used.

Based on the theories of collective unconscious and shared information bias, we propose that scientists try to sway people's minds around climate change.

Hurricanes Ida and the European floods in 2021, for example, should be used to convey the seriousness of climate change to the public. Climate change will be seen as something that affects the daily lives of the public.

A politically independent fact-check system similar to the "We the People" system created by the Obama administration is needed for science. A decision made by people with different political views would make it harder for someone with a particular belief to reject the decision.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

Scientists should try to get social media companies to make better filters for misinformation. It is important that decisions of by fact-check systems are enforced.

It is possible to change public perception with direct action. The Korean scientific community is trying to prevent the spread of yellow dust by planting trees in the Gobi Desert.

It is essential that scientists and engineers pay attention to the social consequences of their scientific claims in order to ensure that the public trusts them. The public may not be swayed by scientific claims.

The views presented in this article are of the authors and do not represent those of their employers.

The views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those ofScientific American.