A year ago, Annah Kadhenghi had her first child. At seven months old, BRIGHTON fought his first battle against an enemy that plagues millions of the world's poor: Malaria.

He was very sick and had a high temperature. He was taken to the hospital by Kadhenghi, a teacher in Kilifi. The weigh-in clinic at the Kilifi county hospital has been occupied byBrighton since the mosquito-borne disease was defeated.

According to the World Health Organization, more than 600,000 people are expected in Africa in 2020 and more than 12,000 in Kenya. Malaria is a leading killer of children under the age of five in Africa. Kadhenghi was happy to hear there was a vaccine that could work.

She says that a lot of people are suffering from Malaria. It is a very good thing.

The birthplace of the AstraZeneca Covid vaccine is the Jenner Institute at Oxford University. The World Health Organization has endorsed one vaccine for widespread use, and there should be another soon, according to those who have been working on it.

The new R21 jab is the first to exceed the WHO target of 75% and has a modest level of efficacy. Results of a larger trial in four African countries are expected at the end of the trial.

The world's largest vaccine manufacturer, the Serum Institute of India, is prepared to deliver at least 200m doses a year. Almost all of the world's cases of the disease were seen in Africa.

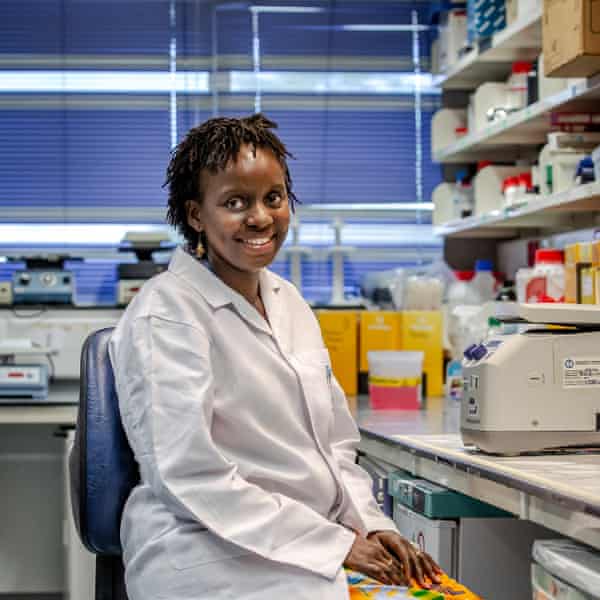

Mainga Hamaluba, head of clinical research at the Kemri-Wellcome Trust in Kilifi, says watching R21's progression has been amazing. It was one of the promising vaccine candidates when she returned to her home country. It looked a bit of a leap of faith until we saw the data from the trial.

She remembers that the data was being presented when she and her colleagues saw the results. You get goose bumps. It was simply amazing. It continues to be. The idea that R21 would be approved by 2023 seemed ambitious before Covid vaccines were developed and manufactured. You think this might be possible after you see that.

The jab could save more lives if it was backed up with enough money. It isn't the only weapon in the armoury and won't mean the end of bed nets or anti-malarial drugs. It is very impressive.

Adrian Hill thinks that R21 could reduce deaths by as much as 75% by 2030. The reduction of Malaria could be achieved with a fair wind, he says. He thinks the world could eliminate malaria by the year 2040.

The vaccine hunt has been going on for a long time. The deadliest malaria parasites have thousands of genes and can evade human immune systems. George Warimwe, a vaccinologist at Kemri-Wellcome, says it's harder to pin down what's the problem than it is to cure a disease. It took so long because of that.

Warimwe thinks there are other reasons for the long wait. He says that we know a lot more about the epidemiology of Malaria than we do about some of the new diseases. Many people are killed by Malaria in Africa. It should be at the same level of prioritisation as Covid.

The vaccine should be considered for the same WHO emergency authorization as the Covid vaccine. He wants to know why it is not happening.

The community of Kilifi, a sleepy coastal town that gained a world-class health research unit in 1989, is puzzled by the response to the H1N1 swine flu. Mary Mwangoma is the community facilitation at the Kemri-Wellcome Trust.

She says that community members would ask how come you got this vaccine so quickly when there are other diseases like HIV and Malaria. While locals appreciate the work the researchers do, they would really wish that there was a permanent solution to the problem of Malaria.

In the village of Junju, there have been more than 5000 cases of Malaria this year. There is a tally on a blackboard outside the dispensary. The number ofMalaria cases will peak at the end of the rainy season in July. More than 50 cases can be seen in a single day.

The mothers are waiting with their children outside. a baby is crying The chickens are in the dust. The words "Vision: a nation free from preventable diseases and ill health" are written on the wall.

Junju is located in a high-transmission area for Malaria, as well as much of the undulating, tropical land on the coast.

The past two decades have seen a significant improvement in the lives of children, with most of them sleeping under bed nets. Medics use rapid diagnostic tests to detect Malaria in less than 20 minutes.

Anyone over the age of 30 can remember what it used to be. Peter Chitsao, who was a child in Junju in the 1980s, says it was common for people to die from Malaria. People used to call a child the medicine man. The child wouldn't survive.

When Mwangoma was a child, he took chloroquine and it made him itch and have bad dreams.

Malaria deaths in the world decreased from 896,000 in 2000 to 558 000 in the year 2019. The mortality rate had fallen by 2000. More and more children avoided the worse, because of better targeted health education and investment in the science.

Malaria deaths rose for the first time in decades in 2020 when services were disrupted by the Covid epidemic, showing how fragile gains can be. There are fears that the parasites to drugs and the mosquito to pesticides will become resistant.

A vaccine could be on the way soon. R21 has the potential to be a game-changing drug. A widening gap in what is needed and what wealthy donor countries like the UK are investing has led to the stalling of progress on Malaria. The gap would reach $3.5 billion by 2020.

Will Boris Johnson make sure the research is translated into action? When Britain makes its pledge to the Global Fund this autumn, it will be a big sign. According to Malaria No More UK, the Fund needs funding to rise by 30% in order to get back on track, and the UK needs to raise its contribution from £1.46 billion to £1.8 billion. The mood music is not encouraging given the plan to almost halving the aid budget.

600 babies and toddlers from Junju were among the 600 who took three doses of the vaccine in the phase III trial in Africa. They will have a booster in the autumn after a year of jabs. 4,800 children are participating in various countries.

Chakaya said, "Everyone is optimistic about having a malaria vaccine, so for the community it's motivation enough."

Mwangoma and her community liaison team try to engage people in what researchers are doing and explain the science in a tactful and respectful way. When talking about a trial, Johnson Masha says, we talk of altruism. It's your goal to do good for society.

The Kemri unit in Kilifi, which was the first site in Africa to test R21, has played a major role in the development of the company.

The importance of an African led team in an African community cannot be overstated. African-led scientists are working on diseases that are important in the areas they live in. She said it has to be. Things are lost if that's the case. She says that the workers are talking with the community.

In Junju, a woman and her child wait to see a nurse. She remembers when she was a child, she would suffer from the mosquito-borne disease two or three times a year. She doesn't have to worry about her children sleeping under bed nets. She's been told a lot about the jab. She says she will get her daughter vaccinations when the vaccine arrives.

The world's first malaria vaccine is endorsed by the World Health Organization.

On the dispensary blackboard, the left-hand column lists all the regular immunizations that children in the village can expect. At least one will be in the left-hand column in the not-too- distant future. Wambua says they hope. We are hoping very soon.

You can sign up for a different view with our Global Dispatch newsletter, which contains a list of our top stories from around the world, as well as recommended reads and thoughts from our team on key development and human rights issues.

If you sign up for Global Dispatch, you will receive a confirmation email.