Every human is colonized by many different organisms that help shape and direct their lives. There is a phenomenon between people and their homes.

Scientists at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine and elsewhere wrote in the June 24, 2022, issue of Science Advances about how the presence of humans changes the biology and chemistry of the house.

The findings should have an influence on future building designs.

Modern Americans spend 70% of their time inside, changing the indoor microbiome with their body's input. The interaction between humans and indoor exposure to pollutants has been studied, but a new study shows how people influence the composition of a home through routine activities.

The home was built in Austin, Texas. The house was designed so that it could be used for ordinary purposes. 45 study participants, plus visitors, spent time in the house, occupying it for six hours per day for 26 days, during which they performed scripted activities, such as cooking, cleaning and socializing, despite the fact that overnight stays were not allowed.

A bleach solution was used to deep clean the house. Researchers said there were still traces of humans in the samples. After almost a month of human occupation, the house was alive with many different types of flora and fauna.

Molecules associated with skin care products, skin cells, drugs, food-derived molecule and human or animal terpene were found by researchers.

Natural products such as food, molecules associated with the outdoors, personal care products and human-derived Metabolites were the majority of the indoor surface molecule.

The most likely sources were food, feces, building materials and the microbes that grow on them.

The kitchen and toilet were the most diverse places in the house. When a subset of chemistry is removed because of the cleaning, it is only temporary and partial, as the sum total of cleaning and human activities overall results in an increase inAccumulation of richer chemistry," the authors wrote.

Tables, light switches and knobs are frequently touched by people. It's possible that the floors were cleaned more often. The least change in chemical diversity was seen between T1 and T2.

Other people living in the area.

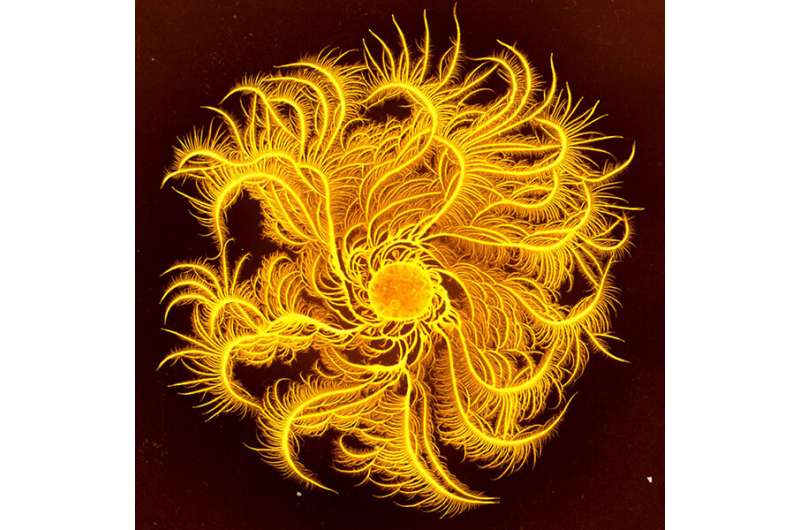

The test home had more than one occupant. Researchers found that the indoor surfaces were covered with many different types ofMicrobes. Different species were able to recolonize cleaned spaces due to regular cleaning.

At the end of the test period, less than half of the house's original Microbiome remained, but it accounted for more than 98% of all life in the house. The majority of the detected microbiome at T2 was derived from humans. Human activities had decimated the free-living environment associated microbes. Clean or push out.

"We don't know how the human-related microbes squeezed out the environmental microbes, but it's clear that they do," said Rob Knight, one of the study's principal investigators. Understanding this phenomenon will be a key goal of future research.

According to the authors, at least one percent of the detected indoor molecule may have an outsized health effect. Coffee is one of the main sources of food-derived indoor molecule detected. The Paenibacillus was found in and around the area where coffee was prepared and in coffee machines. Coffee drinking is associated with improved cardiovascular health and longevity, and may also contribute to human health, as evidenced by the use of panibacillus in chickens and bees.

More studies are needed to understand how the chemical make-up of a home affects building material design to improve human health.

More information: Alexander A. Aksenov et al, The molecular impact of life in an indoor environment, Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abn8016 Journal information: Science Advances