Less than a decade from now, a spaceship from Mars may swing by Earth to deliver samples of the Red Planet's rocks, soil and even air to be scoured for signs of alien life by a small army of researchers. The Mars Sample Return campaign is the closest thing to a holy grail that planetary scientists have ever pursued.

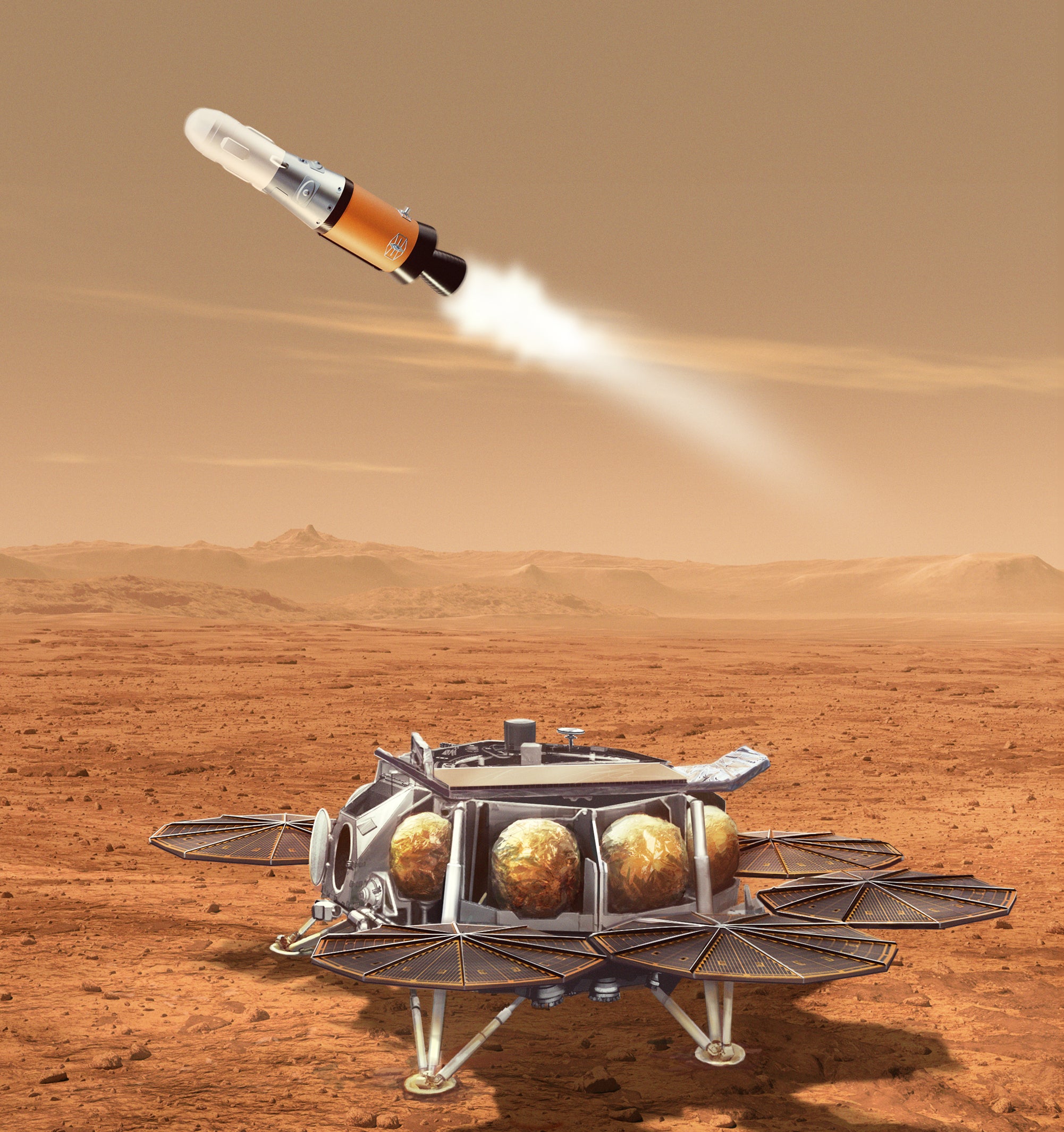

NASA's Perseverance rover is wheeling around an ancient river delta in Mars's Jezero crater, gathering samples for future pick up by a "fetch rover." The design and testing of the Mars Ascent Vehicle is progressing well. One crucial aspect of the project remains troublingly unresolved: How exactly should the returned samples be handled and at what cost, given the risk of possibly contaminating Earth's biosphere with imported Martian bugs.

The hoped-for follow-on of sending humans to Mars is shaped by the answers to these questions. Is it possible for astronauts to live and work on the Red Planet. Can they return home with the certainty that they don't have any Martians? The eventual quandaries will be resolved by the protocols hammered out forMSR.

The Earth Entry System would be a cone-shaped, sample-packed capsule that would be released high above our planet's atmosphere. The capsule will plunge to Earth without a parachute and land in a dry lake bed. The capsule will be designed to keep its samples isolated despite hitting at 150 kilometers per hour. After it is recovered, it will be placed in a protective container and shipped to an off-site facility. A facility like today's biolabs that study highly infectious pathogens could be similar.

NASA deems the ecological and public- safety risks of this proposal to be extremely low. Some people disagree. The space agency solicited public commentary on an associated draft environmental impact statement, which resulted in 170 comments, most of which were negative regarding a direct to Earth, express mail concept of Mars collectibles.

Are you not focused on the task at hand? One person suggested that it wasn't just no, buthell no. One person said that no nation should endanger the planet. As the knowledge of NASA's intentions are spread beyond the smaller space community, public opposition will rise dramatically. It was suggested by many of the respondents that any shipment of specimen should be first received and studied off- Earth, an approach that could easily become a logistical nightmare.

Steven Benner, a prominent Astrobiologist and founder of the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Alachua, Fla., said that he does not see any need for long discussions about how samples from Mars should be stored. Material that ends up on Earth comes from space rocks hitting Mars. According to current estimates, about 500 kilograms of Martian rocks land on our planet annually. He has a five- gram hunk of Mars on his desk that is alluding to that fact.

trillions of other rocks have made similar journeys since life appeared on Earth. It has already happened, and a few more kilograms from NASA will not make a difference.

Benner says NASA seems to be caught in a public relations trap of its own making, honor bound to debate the supposed complexity of what should really. NASA knows how to look for life on Mars, where to look for life on Mars, and why the chances of finding life on Mars are high. NASA committees seek consensus and conformity over the basics of chemistry, biology and planetary science that must drive the search for Martian life, which will cause the launch of missions to be delayed and the cost to increase.

Benner says that they ensure that NASA never flies life detection missions.

There is a growing sense of urgentness among U.S. planetary scientists. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine gave NASA the latest Decadal Survey on planetary science and Astrobiology in April. One of the report's main recommendations calls for the agency to shore up its plans for handling MSR's samples, with an emphasis on readying a Mars sample receiving facility in time to receive material from the Red Planet by 2031.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

Philip Christensen, a professor at Arizona State University and co-chair of the new Decadal Survey's steering committee, says that NASA needs to start designing and building a facility immediately to meet that deadline.

The recommendation was not to build a very fancy, very complicated receiving facility. Make it easy to understand. The first thing to do is to make sure the samples are safe, then let them go to labs around the world that already have very sophisticated equipment.

John Rummel agrees that simplicity can save time but it can also be costly. He says that no one wants to spend all the money in the world on a Taj Mahal. If scientists are not allowed to properly investigate whether any returned samples harbor evidence of life, building a bare-bone facility could backfire.

Rummel says that it isn't true that we know enough about Mars to estimate the risks of interplanetary spillover. We don't know a lot about Mars. That is the reason we want the samples. From the standpoint of potential life elsewhere, we find Earth organisms doing new things. We don't think we need to be cautious. The answer is that we need to be cautious. The unknown has to be respected by people. The public is served by your caution if you have that respect.

The threat that negative public opinion poses for the mission is clear to most participants. Boston is an astronomer at NASA's Ames Research Center. She thinks that getting people interested in the topic would be a better way to push the research forward. The analyses of the Mars samples will be used to answer the science questions, but they will also be used to protect the Earth.

While a chilling effect from harsh handling restrictions forMSR's samples seems more probable than the eruption of a Pandemic, some argue that it isn't very expensive.

Tax payers will have invested at least $10 billion to bring these samples to Earth, according to an astronomer who succeeded Rummel as NASA's planetary protection officer. Wouldn't it be better to spend 1 percent more to build the best facilities and instruments for studying these samples while also making sure that the only planet we can live on isn't damaged?

The debate is complicated by the fact thatMSR is not alone in its quest for Red Planet rocks, and other projects may not follow its rules. China recently announced its own independent plans to bring Martian material directly to Earth, possibly earlier than the NASA/ESA Mars Sample Return campaign.

Barry DiGregorio is an astronomer and founder of the International Committee Against Mars Sample Return. No single country will know what the other has found or what problems they are having with containment unless the return of samples from Mars is done as a global effort in order to share the findings in real time with all spacefaring nations.

DiGregorio believes that priority should be given to ruling out each sample's prospects for harming Earth's biosphere before it is brought back to our planet, something best done in a dedicated space station or an Astrobiology research lab built as part of a lunar base. This concept will likely be a hard sell, but it's the right time to consider it.