The natural world bounced back after the End-Permian extinction, according to paleontologists in the U.K. and China.

According to a review published today in the journal Frontiers in Earth Science, predators became meaner and prey animals were able to find new ways to survive quickly. The ancestors of mammals and birds were warm-blooded.

One of the most extraordinary times in the history of life took place when the mass extinction occurred at the end of the Permian period. The rebirth of life on land and in the oceans was marked by a time of rising energy levels.

The leader of the new study said that everything was speeding up.

There is a big difference between birds and mammals and reptiles. Prof Benton said that reptiles are cold-blooded, meaning they don't generate much body heat themselves, and that they can't live in the cold.

"It's the same in the water as it is in the land," said Dr.Wu. New hunting styles are shown by the fishes, lobsters, and starfishes after the end of themian mass extinction. They were better than their ancestors.

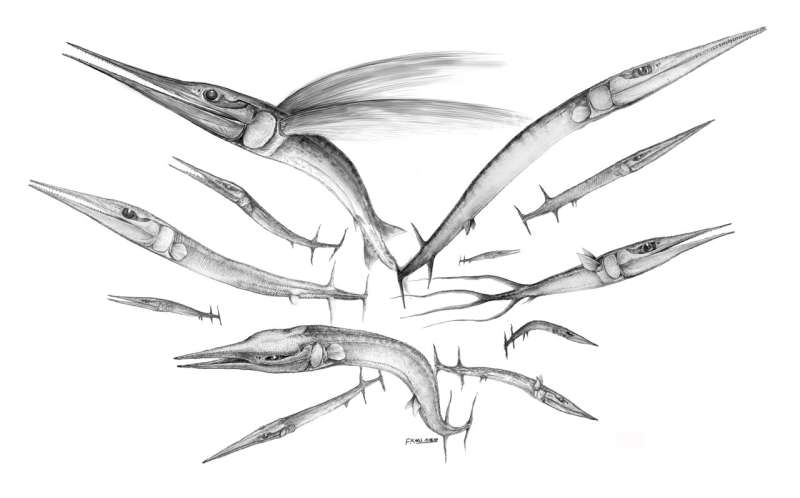

Many kinds of predator that show how new hunting modes appeared earlier than had been thought have been studied by Dr.Wu. Modern-style sharks and the long fish Saurichthys were found by him. The fish was a meter long and it was able to snatch all kinds of prey in its teeth.

Other Triassic fishes from China were able to crush shells. Several major groups of fishes, and even some reptile, became shell crushing. The world's oldest flying fish may have been for escape from the new predatory fish.

There were significant changes on land. Modern lizards have limbs that are stuck out at the side, but the latest Permian reptiles have limbs that are mostly slow moving. They could either run or breathe at the same time, but not both at the same time. This reduced their strength.

The origin of warm-bloodedness in birds and mammals has been a topic of debate for a long time. They can be traced back to the Carboniferous over 300 million years ago. According to others, they became endothermic in the middle of the last Ice Age. The study of the cells in their bones and the chemistry of their bones suggest that both groups became warm-blooded in the aftermath of the mass extinction.

The origins of endothermy in birds and mammals in the Early to Middle Triassic are suggested by two other changes. They could make strides if they stood high on their limbs. The level of endothermy probably goes hand-in-hand with this to allow them to move fast and for a long time.

The Early and Middle Triassic bird and mammal ancestors had feathers in the bird line. As the world rebuilds itself after the end-Permian mass extinction, all the evidence points to major changes in these reptiles.

Animals on land and in the ocean were using more energy and moving faster. Biologists refer to these kinds of processes as "arms races". The other side has to as well if one side speeds up and becomes more warm-blooded. Competition between plant-eaters or predator is affected by this. If the predator gets faster, the prey does the same to escape.

It was the same under the water. The animals had to develop defenses as the predator got smarter. They became faster in order to help them escape.

The ideas are not new. The new thing is that they were all happening at the same time. Positive aspects of mass extinctions are emphasized by this. It was terrible news when mass extinctions happened. The mass clear-out of ecosystems gave a lot of opportunities for the biosphere to rebuild itself.

More information: Michael J. Benton et al, Triassic Revolution, Frontiers in Earth Science (2022). DOI: 10.3389/feart.2022.899541 Journal information: Frontiers in Earth Science