There are oil slicks in the water. Where are they coming from? Keeping an eye on the slippery streaks on the sea surface is no easy task. The first global map of oil slicks is said to have been created using the unique capabilities of satellites. The vast majority of oil came from human-linked sources, according to the results published in Science.

There are sheets of oil. Light can pass through them in satellite images, so they don't appear to be different colors from the ocean. The slicks change the way the water reflects sunlight, just as gasoline leaking from a car can cause a rainbow sheen in a street puddle. Oil-covered patches of the ocean's surface look calmer and smoother when it is windy. The researchers used a computer program to look for the fingerprints of oil in more than half a million radar images collected by the European Space Agency. The scientists spotted slicks as small as a few city blocks and as large as 80 percent of the ocean surface.

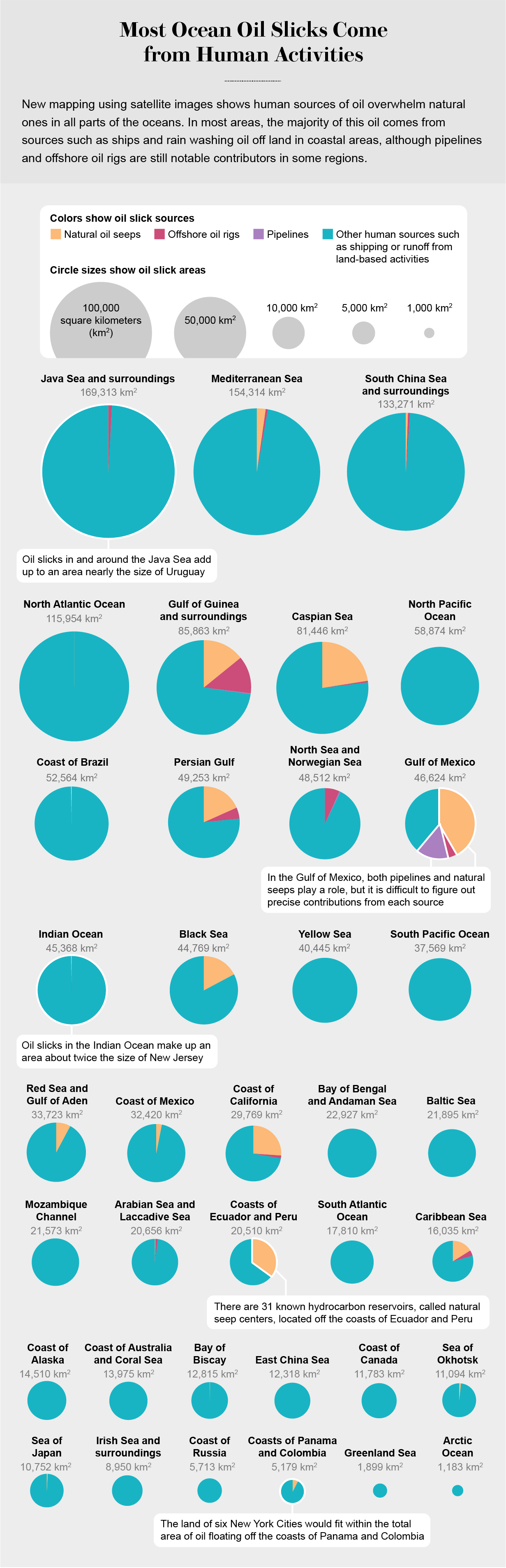

The largest oil slicks were found in the Java Sea between several islands of Indonesia. The researchers spotted a third of the oil in the slicks. The Caspian Sea had the highest concentration of oil in it, with 20 percent of the water covered in oil slicks.

The authors of the study wanted to identify sources as well as locate oil slicks. Their original goal was to find areas where oil naturally occurs. Natural slicks tend to be long-lived in one place and can be seen again and again in the five years of satellite images used in the study. There are oil slicks in the Gulf of Mexico, the coast of California, and the coastal region of South America.

The new findings doubled the number of natural slicks, and the researchers also noticed many more of them. Satellite images can show ships and platforms. It was thought that natural seep and oil from human activities were the same. Over 90 percent of all oil leaks in the oceans come from humans, according to new findings.

Most of the human oil footprint was concentrated in a small area. The population of the planet has gone up by two billion. How many people are there? Ian MacDonald is a Florida State University oceanographer. You have industrial and road networks with that growth. The oil comes from the water.

The study found that the greatest contributions came from areas with oil infrastructure such as the North Sea. It is difficult to single out oil leaking from a source in the Gulf of Mexico because it is also home to one of the largest natural seeps. A tiny fraction of oil coverage was accounted for by leaking drilling platforms and punctures. Most of the 550,000 square miles of human-related slicks came from oil left behind by ships and washed off the land by rain. MacDonald says that they have a global supply chain. The amount of international shipping ocean has tripled since 2000.

In major port regions such as the South China Sea, there were signals that pointed to shipping. There were 21 oil slicks spotted near ships and in shipping lanes in the open ocean. Small-scale spills are dominating, rather than the big ones that capture the media attention and the public imagination, according to Ira Leifer, an oil seep scientist and CEO of a green-tech company. He wrote an article in Science about the impact of oil on the marine environment. I didn't think about it, so I didn't expect that. It is one of those instances where you can give Homer Simpson a shout out.

A method for assessing the effectiveness of efforts to prevent oil spills is suggested by Leifer. He cautions that spotting oil at sea doesn't mean that it will cause immediate damage. Although high concentrations of oil in the water are harmful to marine life, some organisms can break down the slicks to use as food. It's important to study how much oil is too much.

According to Deborah French McCay, an oceanographer and director of research and modeling at the RPS Group, the oil slicks discovered in the study could point to where other industrial pollutants that can't be seen remotely or broken down by organisms are likely to be found. She was not part of the study.

It is hoped that exposing the vast amount of human-related oil slicks will inspire international cooperation to better protect marine environments. She says that the footprint of oil slicks can be seen as a sign of human activity. The results will alert humans to the ways in which the ocean is being stressed.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.