Most of what we know about human history is wrong according to a book. The established story that has been repeated by brand writers such as Steven Pinker and Yuval Noah Harari is that we lived in small groups of people. They say that all of that is based on outdated information.

None of the authors of the bestselling books are archaeologists or anthropologists. Two years after his death, Graeber was thought to be one of the leading anthropologists of his generation. The co-author is an expert in archaeology.

Both disciplines have been dismissed as easy options with one foot in the humanities and the other in the sciences. Critics say that the problem of getting empirical evidence that is common to both fields is the reason for too much imaginative interpretation.

According to The Dawn of Everything, if there is creative myth-making, it has been most often carried out by outsiders, such as economists, psychologists and historians. The picture comes in two different forms. Pinker argues that modern civilisation is a story of progress away from our brutish origins. The loss of freedom is associated with the loss of civilisational progress. The idea of historical determinism is endorsed by both camps.

The emphasis for change in human choice is what the teleological approach ignores. They argue that our prehistory was made up of many different social arrangements, some involving large cities, some monarchical, and some with slave labor. They say that after the arrival of agriculture, there was no fixed model of community organisation but rather a rich diversity of societies, using agriculture but not succumbing to its social demands.

The slogan "We are the 99%" is often attributed to Graeber, who was involved in the first days of the movement. The professor of comparative archeology at University College London is sympathetic to the political ideas of Graeber.

The book wants to do more than simply rewrite the past. It wants to use the past to inspire today's politicians. They say that if a genuine sense of freedom in how we organised ourselves was fundamental to our prehistory, then maybe it's the key to our liberation in the future. "It's time to change the course of history, starting with the past" is the ad campaign's slogan.

The book has captured the imagination of the public and has been translated into 30 different languages. In the year 2021, it made most of the books of the year lists, and this year it has been nominated for a political writing prize. The Dawn of Everything has attracted some pointed criticism, with a number of suggestions that the authors either misinterpreted or misrepresented their extensive research material, and specifically that they made claims that were not supported by the evidence.

Have any of the criticisms made you rethink?

When it addresses what we wrote, he is open to criticism. I haven't seen anything yet that makes me stop and think.

He doesn't have time to keep up with all the reviews and reactions of the book. He wrote a response to a review in the New York Review of Books. It accuses the authors of making ideological arguments that are not in line with the studies they cite.

The political underpinning of the book is something Appiah is most interested in. The authors argue that the "standard historical meta-narrative" about the progress of human civilisation was invented to exclude the "indigenous critique" by native peoples who took exception to the culture and practice of colonialism. Appiah suggests that the main thrust of social evolutionism was ignored to arrive at this conclusion.

He writes that the intellectual history of the two men could be wrong. They use a few rhetorical strategies in their mode of argument. The bifurcation fallacy is when we are presented with a false choice.

There are discrepancies between the sources they cite and the conclusions they reach, according to him. In the NYRB, Appiah responded to the reply with claims of misrepresentation. The philosopher concluded by celebrating the work of two remarkable scholars that their intelligence, imagination, and surly sense of humor make up almost every page.

Despite those warm words, the criticism hasn't been completely forgotten. It doesn't sound bitter at all. He says that Anthony Appiah was a fan of it. That is hard to comprehend. It seems like it's as unutopian as possible.

The word utopian is not the right word. The authors made a point of rejecting Rousseau's romanticising of thenoble savage. It is fair to say that many of their characterisations of earlier forms of social organisation tend towards the most progressive.

The Enlightenment was inspired by the indigenous critique encountered by early colonialists according to David A Bell. Bell felt that he wasappalled by the understanding of the French Enlightenment that was given to him by the two men. He accused the authors of coming dangerously close to scholarly malpractice.

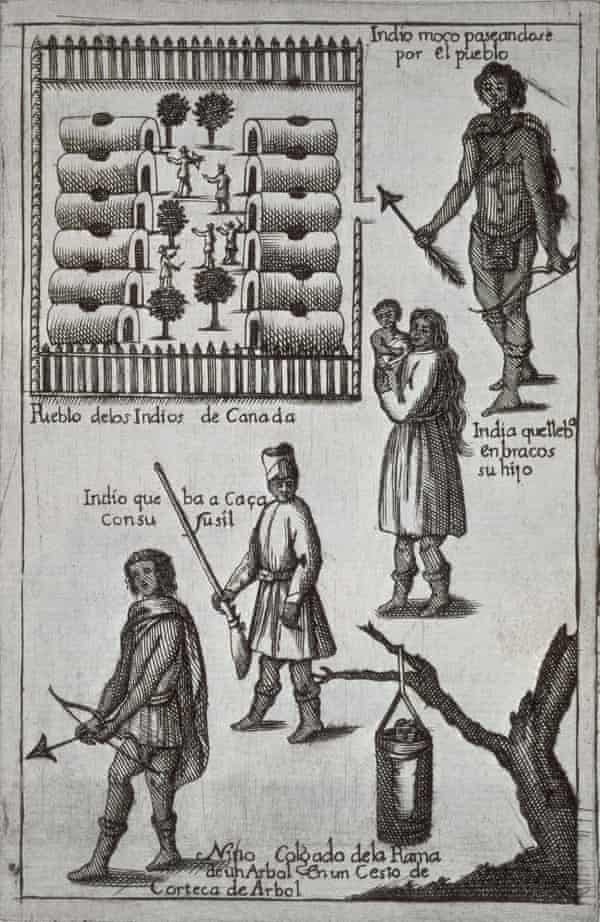

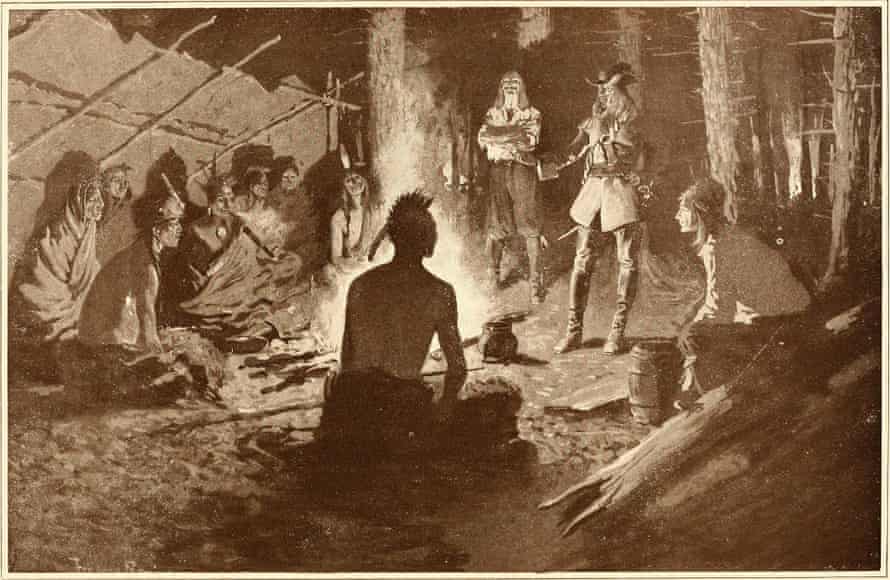

The Baron de Lahontan is a French nobleman who wrote a book based on his travels. Adario, who makes an astute critique of the European outlook and offers progressive views on religion, is really just a nickname for a real-life Native American diplomat and warrior, according to the authors.

They claim that the arguments made by Adario/Kandiaronk helped shape the French Enlightenment. Bell believes that this is an egregious error that stems from a false understanding of 18th century literature, which used Indigenous people to ventriloquise the progressive opinions of the day.

He believes that the Dialogues are not part of the tradition. He thinks Prof Bell has taken a step off the precipice by comparing Lahontan to Gulliver's Travels.

He doesn't show that he's troubled by the attacks. He admits that he sympathizes with the likes of Pinker and Diamond because he understands that they get "condescended to" for being bestsellers even though they put in a lot of effort. He admonished them for their "terribly outdated ideas about human pre history".

The academic reactions to The Dawn of Everything are starting to come through. The early signs are intriguing. The book is being cited as the reason why students apply to do archaeology courses because of the response from his fellow archaeologists. Since Indiana Jones escaped from the snake pit, this is the biggest boost to the field.

On the day before I met him, he was in Berlin promoting the book and a few days later he was going to Canada to meet Indigenous people.

He must engage without the co-author with whom he spent 10 years writing the book. Some of his family believe that he may have been related to Covid.

He says he misses his input every day. It is very odd to be confronted with David every day, not having had the chance to grieve fully. He would want me to do it and expect me to be out there doing it. I continue to do it. I am aware that grief is not normal. When I slow down and have time to reflect, it will hit me that he has left.

He wants the book to start a conversation about change. The question of how or why human society came to be stuck in the paradigm he and Graeber describe is likely to come up in the debate.

There is no one answer according to him. He believes that the lessons to be learned are not about the effects of the agricultural revolution or urban revolution. The freedom to rethink the social order is the most important thing.

It seems like it's uncontentious. Can a world of 7 billion people who want an improved material life expect to enjoy the same liberties our ancestors did tens of thousands of years ago? Is it possible when all is done?

The answer would be to point out that what we have now is not feasible. We will probably not be here if we keep doing this.