A small silver coin with the name of a famous viking king was found in southern Hungary.

It's possible that the coin arrived with the court of a medieval Hungarian king, which has puzzled archaeologists.

Even though it's made from silver, the early Norwegian coin was worth less than $20 in today's money.

The denar used in Hungary at the time was equivalent to this penning, according to Mté Varga, an archaeologist at the Rippl-Rnai Museum. It might be enough to feed a family for a day.

RECOMMENDED VIDEOS FOR YOU...

There is a rare gold coin in Hungary.

The silver coin was found by metal detectorist Zoltn Csiks at an archaeological site on the outskirts of the village of Vrdomb.

The remains of the medieval settlement of Kesztlc can be found at the Vrdomb site. Archaeologists have made hundreds of finds there.

Varga said there is a lot of evidence of contact between Hungary and Sweden.

This is the first time a coin from the Nordic countries has been found.

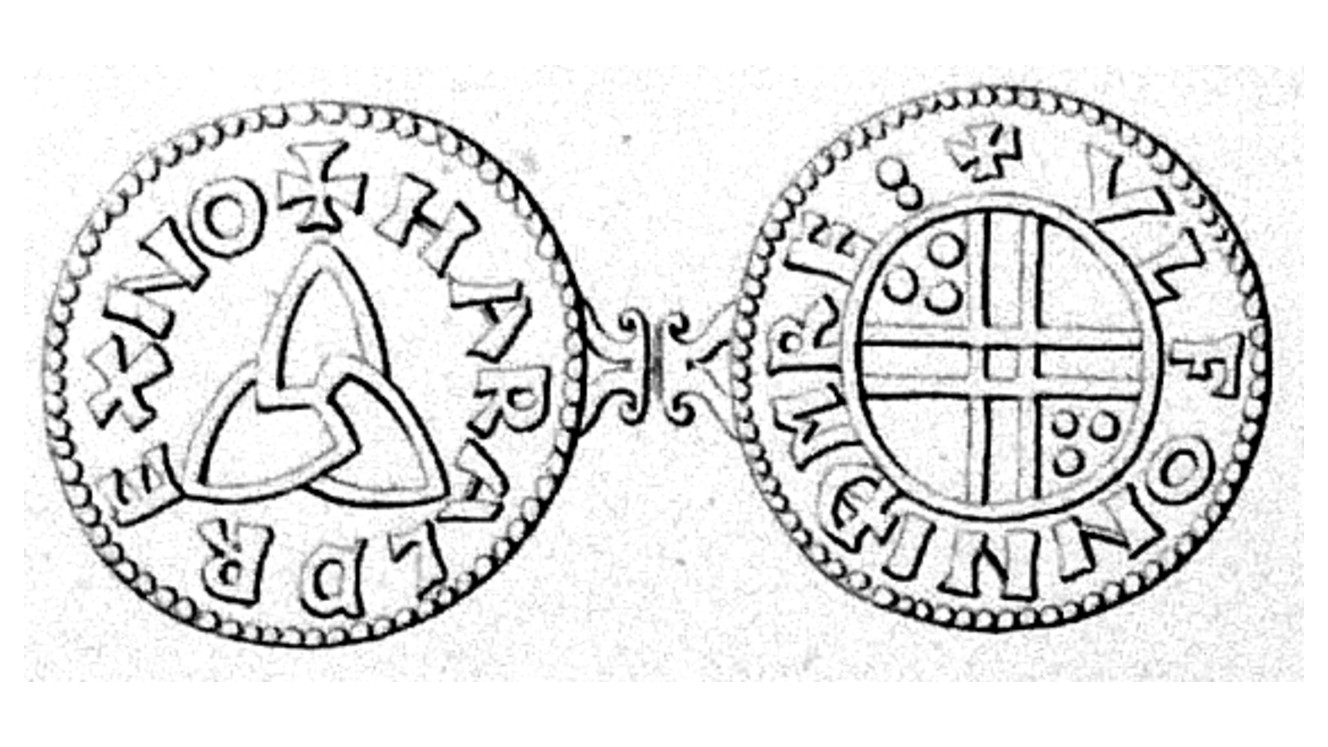

The coin found at the Vrdomb site is in poor condition, but it is recognizable as a Norwegian coin from 1046 to 1066.

The front of the coin has the name of the king of Norway on it and is decorated with a three-sided symbol.

There is a Christian cross on the other side and two sets of dots.

The son of a Norwegian chief and half-brother to the Norwegian king was called Hardrada. The last of the great Viking warrior-kings, he lived at the end of the viking age.

After his half-brother was killed at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030, Harald fled to Russia and then to the Byzantine Empire, according to traditional tales.

He became the sole king of Norway in 1047 after his nephew Magnus died in a battle against the Danes.

In 1066, he tried to take the kingdom from his brother, King Harold Godwinson, by allying with the rebels of Tostig Godwinson.

There is a large amount of gold 'rainbow cups' found in Germany.

The victor and his armies had to cross the country in just a few weeks before the Battle of Hastings against William of Normandy, which Harold Godwinson lost.

It is more likely that the penning was in circulation for between 10 and 20 years, Varga and Németh said.

There is a possibility of a connection with Solomon, who ruled from 1063 to 1077.

Solomon and his retinue were encamped in 1074 above the place called Kesztlc according to a medieval Hungarian illuminated manuscript.

Varga and Nmeth said that the king's court could have included people from all over the world.

Another possibility is that the silver coin was brought to medieval Kesztlc by a common traveler: the trading town was crossed by a major road with international traffic and the previous road was built in Roman times.

They wrote that the road was used by kings, as well as merchants, pilgrims, and soldiers from far away.

Varga said field surveys and further metal detection will be carried out at the site in the future, but no excavations are planned.

It was originally published on Live Science