Scientists warn that monarch butterflies are dying off because of diminishing winter colonies. The summer population of monarchs has remained relatively stable over the past 25 years, according to research from the University of Georgia.

According to a study published in Global Change Biology, population growth during the summer compensates for butterfly losses due to migration.

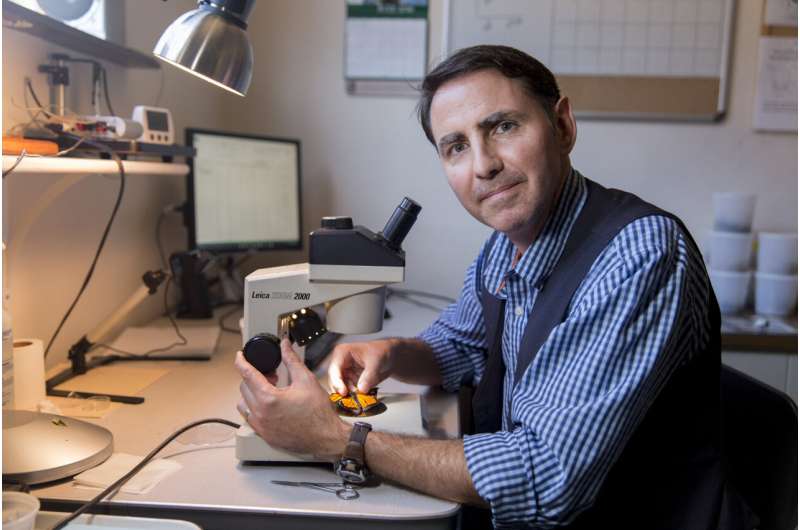

Andy Davis is an assistant research scientist in the UGA's Odum School of Ecology and is the corresponding author of the study. They're doing well despite what everyone thinks. One of the most common butterflies in North America is the monarch.

The study authors caution against being lulled into a false sense of security due to the fact that rising global temperatures may bring new and growing threats to all insects.

The co-author of the paper said that there are some butterfly species that are in trouble. A lot of attention is being paid to monarchs, and they seem to be in good shape. It seems like it could have been better. We don't want people to think insect conservativism is unimportant. Maybe this insect isn't in as bad of a situation as we thought.

The largest and most comprehensive assessment of the monarch butterfly population has been done.

The researchers used 135,000 monarch observations from the North American Butterfly Association to look at population patterns and possible drivers of population changes.

Every summer, the North American Butterfly Association uses citizen-scientists to document butterfly species and counts. Each group of observers has a defined circle that spans 15 miles and they count all the butterflies they see.

By carefully examining the monarch observations, the team found an annual increase in monarch relative abundance of 1.31%, suggesting that the breeding population of monarchs in North America is not declining on average. The butterflies' summer breeding in North America makes up for the decline in winter populations in Mexico, according to the findings.

The race to Mexico or California may become more difficult for the butterflies as they face traffic, bad weather and more obstacles along the way. Fewer butterflies are crossing the finish line.

When they return north in the spring, they can make up for the losses. The right resources allow a single female to lay 500 eggs. The colony decline is almost like a red herring. They're not representative of the whole population. The recent increase in winter colony sizes in Mexico isn't important to some people.

Monarch migration patterns are changing.

The national decline in milkweed, the only food source for monarch caterpillar, is a concern for the environmentalist. According to Davis, the study shows that monarchs have all the habitat they need. The researchers would have seen that if they did not.

It is thought that monarch habitat is being lost but not for monarchs. Monarch habitat is a people's habitat. Monarchs use the landscapes we have created for ourselves. All of that is monarch habitat.

Some researchers believe that monarchs may be moving away from Mexico due to the fact that they have a year-round presence in some parts of the U.S. People plant non-native milkweed in San Francisco in order to host monarchs. Florida's climate is an alternative for monarchs due to fewer freezes each year.

The idea of an insect apocalypse is out there. It is not that easy. Some insects will be hurt and some insects will benefit. To get the true picture of what's happening, you have to take that big pig picture at a continental scale.

The paper was co-authored by a number of people. The University of Delaware's Michael Crossley is the first author of the paper.

More information: Opposing global change drivers counterbalance trends in breeding North American monarch butterflies, Global Change Biology (2022). Journal information: Global Change Biology