The past two years have taught us not to take things for granted. Relationships, trade and privileges were disrupted by the Pandemic.

I've traveled to see some of the greatest sights in the sky as a chaser. Thanks to the convenience of the global travel network, I have been able to check off most of the entries on the bucket list. When it stopped in 2020 I realized how lucky I had been.

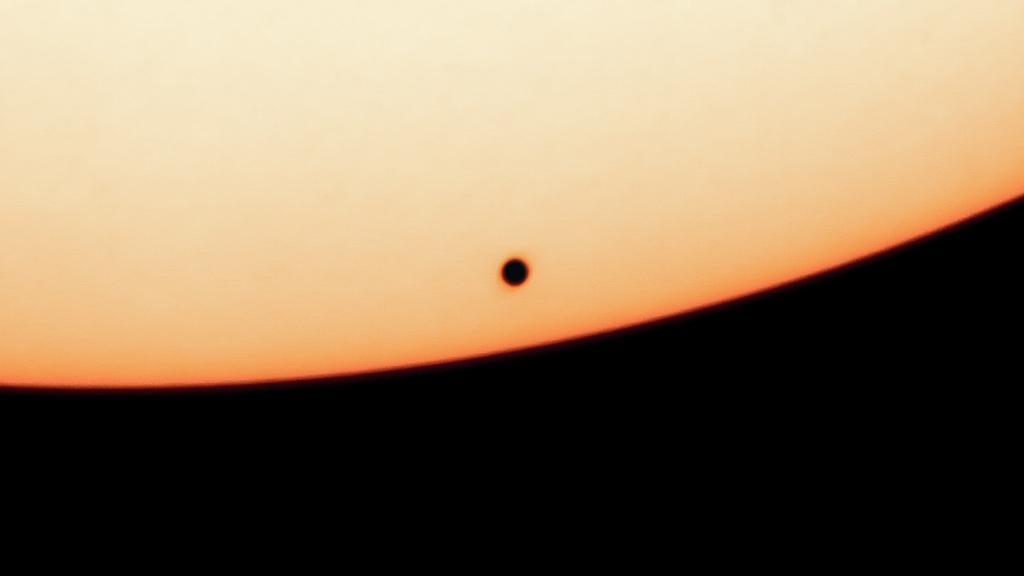

Some events are too rare now that the opportunities are coming back. Ten years ago, I embarked on a 16,000-mile trip to witness a transit of Venus that would never happen again in my life.

Astrophotography and skywatching can be done in a number of places.

The ability to travel and the power of modern astronomy made this possible. It's almost impossible for anyone to be taken by surprise with a comet or supernova. Eclipses won't show up on us again.

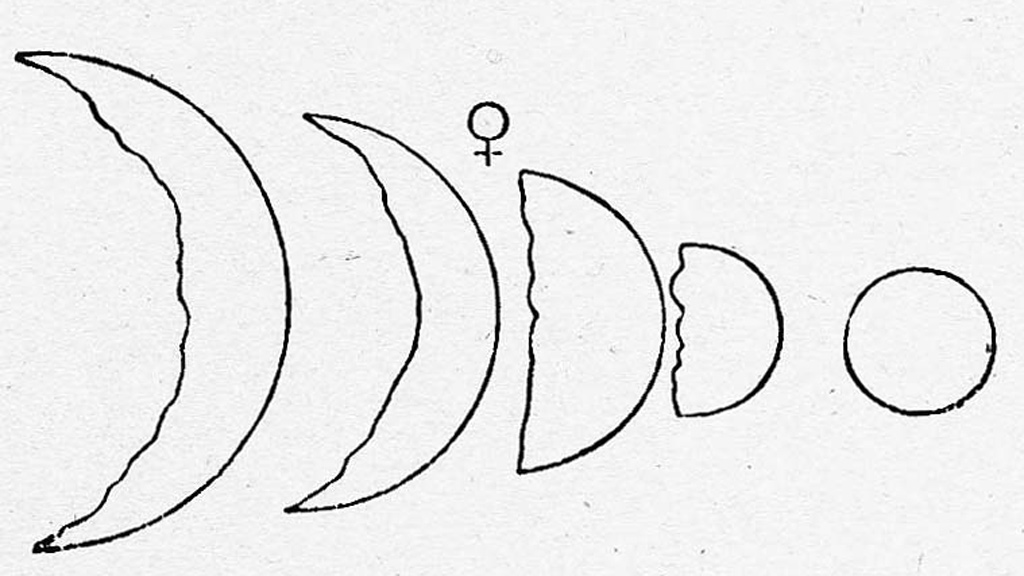

We didn't always have the ability to predict things. Galileo published his drawings in 1623 after observing the phases of Venus. The world's most accurate tables of the solar system were published by Johannes Kepler. The tables were good but not perfect.

Mercury and Venus would transit across the face of the sun in 1631. A near miss of Venus and the sun was predicted by him. The Venus transit of 1631 occurred on schedule in December, but those that wanted to view it were hampered by poor weather and only marginal visibility. It was the only phase of Venus that Galileo didn't see in his lifetime, but he did live long enough to see the next one.

Horrocks used his own observations and math skills to improve on the tables. He predicted a transit of Venus just a few weeks before it happened. Horrocks was the only person in the world to have seen a transit of Venus. Even though he was still alive, Galileo lost most of his sight by 1638.

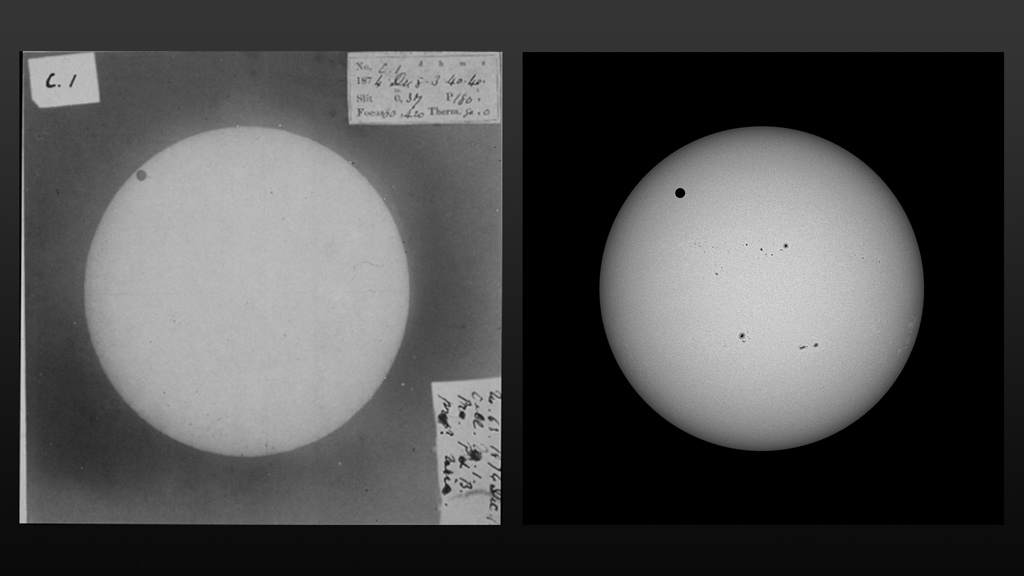

In 1761, the last Venus transit occurred, as predicted by Kepler. The pairs are separated by eight years but have more than 100 years between them. The last transit took place 10 years ago and, with this in mind, I made every effort to see the whole thing.

The transit of 2012 took place over six and a half hours beginning on June 5 and lasting into the next day with visibility centered over the Pacific Ocean. It was widely seen in the U.S., Europe, East Africa, Asia and Australasia, but one particular location promised full visibility at high altitude.

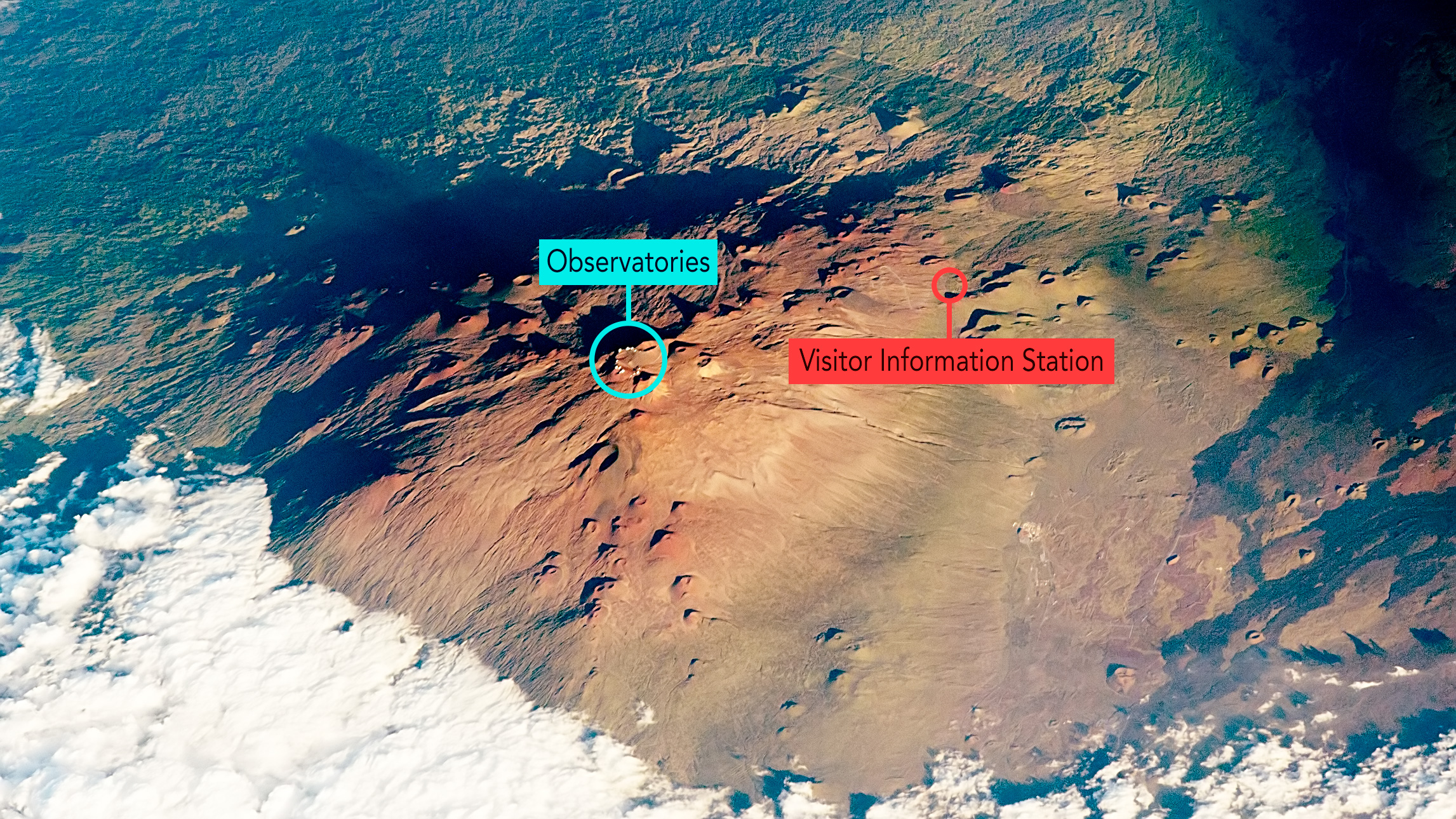

I made a plan with hundreds of other skywatchers to see the transit from the slopes of the tallest volcano on Earth. The summit is home to some of the world's most powerful and prolific telescopes, but a long visit in such thin air can be dangerous.

I was out of breath when I went to the summit. The Visitor Information Station at 9,200 feet above sea level is a great place for travelers to set up their telescopes.

After seeing a partial lunar eclipse on June 3 and 4 when they arrived in Hawaii, spirits were high. The eclipse was a great sight, but just a warm up for what was to come.

Two small telescopes were set up at the Visitor Information Station on the morning of June 5. I spent days in London testing them with my camera equipment to make sure I made good observations.

If you want to observe transits of Venus or Mercury and solar eclipses, you need to use a solar filter.

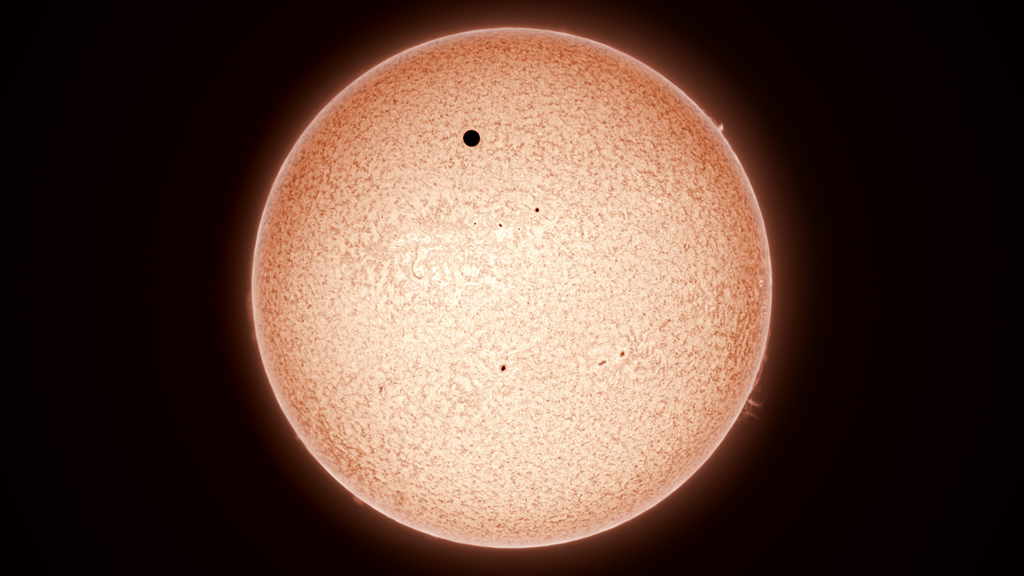

I had the telescopes set up quickly and I was prepared for the main event. The crowd was quiet as they waited for the event to start. The silhouette of Venus was visible on the sun's face after noon.

A chorus of vocal awe erupted across the crowd of skywatchers, climaxing in cheers of excitement as Venus' night-side began its rapid entry onto the disk of the sun.

Through the clear air, every view looked razor sharp, and the hours that followed offered ample opportunities to appreciate the sheer scale and contrast of our neighboring planet. Venus looked amazing through a telescope.

I looked out at the most volcanic planet in the solar system and felt closer to Venus than I actually was.

I was the first person to travel from London to Hawaii to see a Venus transit, thanks to the efforts of previous generations of astronomer.

George Tupman led an expedition from England to Hawaii in 1874 and later published a collection of observations. Like James Cook before him, Tupman knew how important it was to seize the chance.

Edmund Halley suggested that the timing of transits from multiple locations could be used to measure the solar system's size. The contact points, where the edge of a planet and the edge of the sun appear to touch, seem to occur at slightly different times due to the parallax angle.

Mercury transits were also used for these important determinations, but the rarity of Venus transits, combined with the relative size of the planet, engendered a sense of urgency within the astronomy community.

Even though scientists are more confident of the distances, they still need to catch something rare and spectacular to make the most of it.

Only a small group of people will live long enough to see the next transit in 2117. If I live to be 131 years old, I will return with a full report.

Mercury transits are more common than you might think.

We had two Mercury transits in the last two years, but the next one won't be until 10 years from now.

Mercury and Venus are close to the Earth, so transits are rare. The planet has to come between the Earth and the sun in order to hit one of the two points where it crosses that of Earth.

The combination is rare. Being closer to the sun and completing each circle more quickly provides more opportunities for transits. The moon is one of the natural objects in the sky that can produce transits.

Two to five transits per year are created by the moon when it coincides with the sun. We call these events solar eclipses, but they are also transits, as we see one object block our view of another.

There will be lots of solar eclipses in 2032, keeping us entertained. There will be a partial solar eclipse on October 25 in Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia and Africa. There will be a total solar eclipse in the South Pacific on April 20,23. On October 14, a solar eclipse will fall over the United States, Central America and South America.

Most of the world's population will have the chance to see part of the sun's face covered by the new moon between now and the end of the decade. There will be a solar eclipse in the United States in April of 2024.

Most eclipse-chasers will need to travel to see the best views. If you want to catch the next transit of Venus, the best plan is probably a good diet, regular exercise and anything else that will help you live a long time. I wish you good luck.

You can follow Tom Kerss on the social networking site. We encourage you to follow us on social networking sites.