Australian researchers have located a plant that is at least 4,500 years old and is believed to be the largest plant on Earth.

Researchers from The University of Western Australia and Flinders University found the ancient and incredibly resilient seagrass.

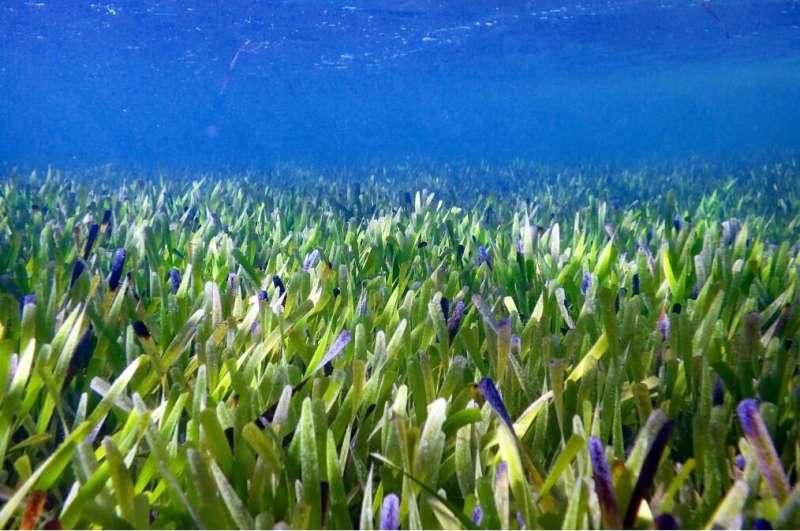

The Posidonia australis was discovered in the shallow, sun-drenched waters of the World Heritage Area of Shark Bay in Western Australia.

The project began when researchers wanted to understand how diverse the seagrass meadow in Shark Bay were, and which plants should be collected for restoration.

We often get asked how many different plants are growing in the same area, and this time we used genetic tools to answer it.

Jane Edgeloe, lead author of the study, says the team used 18,000 genetic markers to create afingerprint from samples of seagrass shoots.

The answer blew us away, and it was the largest known plant on Earth.

The existing 200 km 2 of ribbon weed meadow appear to have expanded from a single, colonizing seedling.

Dr. Martin Breed was part of the research group. The study presents an ecological dilemma.

This plant may be sterile because it doesn't have sex. It is really puzzling how it has survived for so long. Plants that don't have sex tend to have reduced genetic diversity, which they normally need when dealing with environmental change.

Our seagrass has seen a fair amount of environmental change. It has a range of average temperatures from 17 to 30 degrees C. From darkness to high light conditions. Plants would be very stressed out by these conditions. It seems to keep on going.

How does it do that? Dr. Breed says that its genes are well-suited to its local environment and that it has subtle genetic differences across its range that help it deal with the local conditions.

Dr. Sinclair said that this seagrass plant is a polyploid, meaning it has twice the number of chromosomes as its oceanic relatives.

When diploid plants hybridize, whole genome duplication through polyploidy occurs. The new seedling has 100 percent of the genome from each parent, rather than 50 percent.

Polyploid plants are often sterile, but can grow if left undisturbed, and this giant seagrass has done just that.

Even without successful flowering and seed production, it appears to be really resilient, experiencing a wide range of temperatures and salinities plus extreme high light conditions, which together would typically be highly stress for most plants.

The researchers have set up a series of experiments in Shark Bay to understand how this plant thrives in variable conditions.

More information: Jane M. Edgeloe et al, Extensive polyploid clonality was a successful strategy for seagrass to expand into a newly submerged environment, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2022.0538 Journal information: Proceedings of the Royal Society B