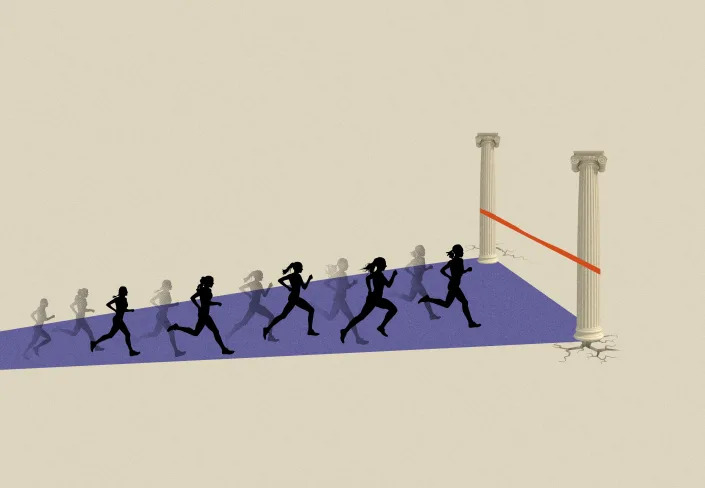

The landmark law banning sex discrimination in education, colleges and universities is being circumvented by manipulating athletic rosters to appear more balanced than they are.

By packing their women's teams with extra players who never compete, double- and triple-counting women while undercounting men, and even classifying male practice players as women, schools across the nation conjured the illusion of thousands more female athletic opportunities.

More than half of the women on the Florida State University indoor track and field team never competed indoors. The school counted its track athletes twice.

Title IX: Falling short at 50 exposes how top U.S. colleges and universities still fail to live up to the landmark law that bans sexual discrimination in education. Title IX requires equity across a broad range of areas in academics and athletics. Women are struggling for equal footing at many colleges and universities despite tremendous gains over the past five decades.

More than a third of the 165 athletes on the University of Wisconsin's women's rowing roster never raced for the school. Some women quit before the season started.

At the University of Michigan, 29 athletes on the 43-player women's basketball roster were actually men who signed up to practice.

It's a far cry from what Carol Moseley Braun envisioned when she co-sponsored a law requiring schools to report their athletic numbers to the federal government.

Braun told USA TODAY that they are sleazy. People know they shouldn't do it, but they do it anyway.

Title IX was supposed to close the gender gap in college athletics by requiring schools to provide men and women equitable opportunities to play sports.

The reporting found that schools have abused accepted rules in ways that allow them to comply with the letter of the law while violating its spirit.

USA TODAY found widespread use of roster manipulation in many of the nation's largest and best-known colleges and universities.

USA TODAY's reporting shows that the problem is pervasive throughout the highest level of college sports.

USA TODAY compared the athletic participation numbers schools report to the U.S. Department of Education against four different data sources. 51 Title IX experts and attorneys were interviewed by reporters.

The highest level of public schools in the Football Bowl Subdivision were analyzed by the news organization. USA TODAY filed hundreds of public records requests for the schools and wrote computer programs to collect online rosters and statistics.

The majority of those schools counted athletes in a way that inflated the number of female participants. Sixty-six did so by at least 20 athletes. More than 3,600 additional opportunities for female athletes were added by the schools.

The investigation's findings.

2,252 women's roster spots were created by double- and triple-counting existing athletes, according to the analysis. They double-counted women more often than men. The University of Hawaii netted 78 women's roster spots through duplicate counting, which was more than the men's teams combined.

Twenty-seven schools stuffed their women's rowing rosters with more athletes than needed, including some that added dozens of novice rowers with no experience. The teams averaged more than 90 women. More than one-third of all female rowers filled unnecessary roster spots, based on roster caps set in federal lawsuits at two Division I rowing programs.

At least 1 of every 4 women's basketball players the schools reported to the federal government were actually men. Fifty-two schools counted as female participants at least 601 men who scrimmage with women's basketball teams. The Department of Education has not addressed the problem of counting male practice players toward women's teams.

A total of 170 male athletes were undercounted by 10 schools because they claimed to sponsor no men's indoor track and field team. The schools did not count these athletes because they did not compete. Meet records show that Miami University of Ohio sent 48 male athletes to participate in indoor meets, but did not include any gender equity reports.

Title IX compliance is overseen by the U.S. Department of Education. Athletes must receive genuine participation opportunities in order to count. The department allows inflated numbers to be reported.

The EADA requires the department to publish the schools' reported numbers online. The purpose of the law was to give the public the tools to search and assess if a school gives men and women equal opportunities.

The schools don't think those numbers should be used to assess their Title IX compliance. They keep the real numbers in-house, making it harder for the public to notice and take action.

Braun said that the Department of Education should be vigilant. When female athletes file a federal complaint or a lawsuit, schools are usually held accountable.

Arthur Bryant is an attorney who has litigated Title IX cases for decades. The rules need to be fixed.

USA TODAY reached out to the schools about their use of counting techniques that boosted their female-athletes totals. The athletic department followed federal guidelines and did not intend to deceive.

The Department of Education refused to make officials available for an interview. It was not possible to draw legal conclusions about an institution's compliance with Title IX from EADA data.

Catherine Lhamon is the assistant secretary for its Office for Civil Rights.

Lhamon said that every school has a Title IX Federal obligation to ensure equal opportunity among men and women.

Lhamon said in her statement that the data reported by schools to the federal government can be used to evaluate whether a school offers equitable athletic opportunities, but that the agency looks at other factors when determining compliance with the law.

The first step to increase compliance with Title IX was to require schools to report numbers. Collins spoke about the need for stronger enforcement from the department and how the NCAA would not do the right thing unless forced.

In the 1990s, Trahan was a volleyball player at Georgetown University.

Trahan told USA TODAY that the NCAA and its members have long undervaluing and mistreating women athletes.

College men outnumbered women in both the classrooms and locker rooms when Title IX was passed. Women outnumber men in the classroom but not on the courts or fields.

Colleges and universities have failed to maintain ratios in athletics despite the fact that female college enrollee rates have increased. The percentage of women in NCAA athletes nationwide was just 44% in 2019.

Title IX compliance can be shown by three ways. The gender breakdown of colleges' athletic programs reflect their student bodies.

The other two are showing a history and continuing practice of increasing the athletic opportunities for the underrepresented sex, usually women, or demonstrating that the athletic interests and abilities of their female students are met.

The safest route is proportionality.

Adding new women's sports, each of which could carry a hefty price tag, is what balancing triple-digit football rosters with gender equity requirements means for many schools.

The school will spend $12.5 million on new facilities and an estimated $1.7 million annually to field a women's lacrosse team as part of an agreement to boost its female athletic participation rates.

It is easier for schools to manipulate their rosters than it is to pay bills.

One of the most efficient ways to increase the number of female athletes is by double- and triple-counting.

It is allowed. If athletes compete on more than one team, they can be counted more than once. Rather than counting heads, schools tally the number of participation opportunities they fill each year.

The EADA reporting guide shows an example of a person who plays football and lacrosse and also competes in cross country, indoor track and field and outdoor track and field. The department and NCAA tell schools to count those as three separate teams.

Track and field and cross country athletes are the only athletes who compete on more than one team. They accounted for 98.1% of all duplicated roster spots in the year, according to USA TODAY's analysis of the 95 schools that indicated double- or triple-counting on their gender equity reports to the NCAA. The NCAA reports break down duplicated counts by sport.

These athletes are worth more than their peers for Title IX purposes. Schools take advantage.

While men's track and field and cross country rosters are generally lean, schools often fill women's teams with athletes they don't need. Some women's teams were two or three times the size of their men's teams.

Take Florida State. Florida State packed its women's cross country team with 43 people, while the men's team had 13. USA TODAY's analysis of the squad lists and meet results found that 38 of the women were triple-counted.

In track and field that year, Florida State only counted 38 of its 45 male athletes toward its indoor and outdoor teams, but it did so for 66 of its female athletes. More than half of the women did not compete in any indoor meets that year.

Kelly Aponte said she was surprised to learn she had been triple-counted. She did not run in any indoor or cross country meets that year because of injuries.

Aponte, a 2020 graduate, said that he never actually raced.

I wasn't a top 10 runner. She said that it would have been foolish for the coaches to put her in the competition.

By double- and triple-counting athletes like Aponte, the school claimed to have offered 175 track and field and cross country opportunities to women. Half of the gender participation gap was erased that year.

Florida State has supported women's programs at a championship level and last added a beach volleyball team in 2011.

We report our participation data in accordance with the policies and guidelines provided by the U.S. Department of Education.

A 120-man football roster with a 45 person women's track and field team is not the same as providing equitable opportunities.

He said that Title IX compliance depends on roster spots and not distinct athletes.

I think it does a disservice to women.

Even with the roster manipulation, USA TODAY's analysis found, Florida State would have still needed to add more than 100 female athletes to reach proportionality, which is roughly the equivalent of its entire football team.

levating women's lacrosse would have made it part of the way there.

The lacrosse club at the school has asked the school to be an official NCAA sport multiple times.

There is growing interest in the sport in the state. Women's lacrosse is sponsored by nine of the other 14 schools.

The school turned down their request.

Villalonga and Simkins didn't know that Florida State manipulated its roster count. The lacrosse players might have pushed harder at the last meeting.

Simkins said that the girls on the team were not aware of it. Many of the girls want to play in college.

The problem in many schools comes down to who is doing the counting and reporting, according to a retired Oregon State University athletics administrator. Vydra was supposed to review the numbers before the business office submitted them, but once it didn't show her until after.

She couldn't believe what she saw.

At one point, female hammer throwers were counted as indoor track athletes. She said that nobody is throwing a hammer indoors.

Every fall, the University of Wisconsin women's rowing team hosts an open house at its three-story boathouse on the edge of campus.

If a woman is interested, she can learn about the team and join.

If you were a competitive athlete in high school and ever dreamed of becoming a D-I college athlete, this is your chance to represent the Wisconsin Badgers, read a post on the athletic department website ahead of last year's event.

Dozens of walk-ons started working out with the team along with returners and women recruited out of high school. The competitive season begins in the spring. Some rowers who may get to race in a novice boat and serve as a reserve but do not have their photos and bios on the athletic department website, stayed as novices.

A total of 57 women raced in Wisconsin's lightweight and openweight boats. The school reported its gender equity numbers to the federal government and the NCAA and claimed 165 female rowers, more than its football, men's basketball and men's hockey teams combined.

Several former rowers contacted by USA TODAY said that the experience they had was not close to what they had been told. As D-I athletes, they expected cool gear, exciting road trips and high-level competition, but most of them didn't leave the boathouse.

Teyha Crego said she spent her freshman semester with the team as a member of the land crew. She ran up Bascom Hill. She didn't get on the lake.

At freshman orientation, she was approached about an open tryout. She was shocked when she heard how many rowers Wisconsin had. There are only about 40 rowing machines in the boathouse.

I can't believe that there are 170 girls.

A USA TODAY analysis of Wisconsin's squad list and regatta records found that at least 64 women did not compete in any races that year. Only 44 of them competed in novice boats.

Athletes on many of the Wisconsin teams do not compete outside of practice, but that doesn't necessarily mean their experience as a student athlete is diminished in some way.

Some remain in the program and others decide not to.

Football teams have long been offset by women's rowing teams. Jim Dietz, the former University of Massachusetts women's rowing coach, said that the capacity for large rosters has been a selling point for the sport.

It was cheaper to hire a couple of coaches to coach somewhere from 65 to 80 women than it was to hire three coaches of three different sports to coach 20 women each, according to Dietz, who retired from the University of Massachusetts in 2019. It was attractive to these guys. It was easy to do.

The NCAA adopted a scaled-down, team-based model for the sport that accommodates a maximum of 23 women per school.

Conferences provide for additional boats. More than any other conference, the Big Ten championship accommodates up to 51 women. Most others allow less than 30.

The limits have not stopped schools from overloading their rowing rosters.

The University of Alabama, the University of Tennessee, and the University of Michigan all reported triple-digit women's rowing teams. The conference championship allowed for 28 rowers, but Alabama reported 122.

The University of Washington, Oregon State University, and the University of California, Berkeley sponsored men's rowing. Based on their reported numbers to the federal government, their average roster size was 60.

Despite the fact that women's rowing teams have been capped at much lower numbers, the roster stuffing happens.

In October, the University of Iowa agreed to reduce the size of its squad to no more than 75 athletes. The school relented after members of Iowa's women's swim team sued the school, saying that its rowing count was inflated to skew its overall number of female athletes.

A group of female rowers sued the University of Connecticut in December after the school tried to cut the team. The head coach testified that she was told to keep at least 60 women on her roster even though she said she needed no more than 42.

Iowa and Connecticut have caps on the number of rowers and the number of women who can act as reserves. The analysis found that 27 of the 30 schools with women's rowing teams rostered more women than needed.

Most Division I schools that have football have roster stuffing happening, according to Sanford.

Unless there is a lawsuit, they are not getting looked into.

Cruz was a practice player for the women's basketball team at the University of Oregon. He guarded two-time national player of the year.

I was fighting for my life every day.

Schools often invite male students to scrimmage with women's teams as a way of preparing them for bigger-bodied opponents while keeping their own players rested. Practice players are common in basketball and other sports.

He was surprised and annoyed to learn that Oregon counted him in a gender equity in the upcoming season.

In its EADA report to the Department of Education, the state of Oregon counted a dozen such men and women, including 11 in women's basketball and one on the beach volleyball team.

Vasquez said that it definitely bothered him. Female athletes have been disrespected for too long. How are women not being given the same opportunities yet?

The Department of Education tells schools to count male practice players as women in their annual Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act reports.

Half the schools in USA TODAY's analysis didn't report male practice players on their women's basketball teams. Those that counted counted men on their women's basketball teams as women.

The guidelines for reporting on the EADA form are issued by the Oregon athletic department.

The current year's data shows how many of the participants were male practice players, but not for the previous year. The online database doesn't show that information in the past.

The department pointed to the EADA reporting guide and regulations, which do not provide an explanation, when USA TODAY asked why it instructs schools to report numbers this way.

The picture makes schools look better than they are, because they don't give equal playing opportunities to women.

The NCAA instructs schools not to count male practice players toward women's teams. There were differences of three or more athletes.

Each team's squad list was reviewed to make sure that players who weren't on it were on the athletic department websites. Dozens of women's squad were filled with many of the same people.

The counting method inflated female athlete counts more than any other method.

The highest count of any school was Michigan, which reported 36 practice players across three women's sports. The number of actual female basketball players on the team was less than the number of actual women on the basketball team.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Michigan women's basketball coach Kim Barnes Arico said the high number ensured her team wouldn't be short practice players because of scheduling conflicts. Barnes Arico was asked if she knew the athletic department counted the men toward the women's teams. Sarah VanMetre interrupted the interview and ended it.

Arizona State had 34 practice players on its women's teams, including 24 in basketball, eight in volleyball, and two in water polo.

Neither Arizona State nor Michigan reported any players on their teams.

The school reports the numbers the way the Department of Education instructs, according to the Arizona State athletic department's corporate public relations specialist. She said that if the federal government launched a Title IX compliance review, it would not count male practice players as women.

The universities that accurately report the use of male practice players in connection with their women's sports do not have an advantage in terms of their Title IX compliance obligations.

Arizona State officials do not believe there is tension between the EADA and Title IX compliance.

Neena Chaudhry, general counsel for the National Women's Law Center, said that the Department of Education should stop allowing schools to count male practice players as roster spots for women. It is the easiest method to fix.

Chaudhry said the law was to give the data to students who might be thinking about what schools they want to attend.

During a required review of EADA reporting procedures, Chaudhry and the National Women's Law Center complained to the Department of Education about the issue. The letter said that counting male practice players as women's team participants can make the analysis of participation opportunities more skewed.

The Women's Basketball Coaches Association urged the department to revise EADA reporting instructions so that no athletes of one gender are listed in counts of the other.

The department did not respond to the complaints. The public comment period for the law was announced on May 6.

Trahan, a former Georgetown University volleyball player, called the use of roster padding "indefensible".

Shame on the athletic directors and college presidents who turned a blind eye to this injustice, and the NCAA should be embarrassed for their role in it as well.

The Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism is at Indiana University.

Reporting and analysis are done by Nancy Armour, Rachel Axon, Steve Berkowitz, and others.

There are data and public records.

Peter Barzilai, Chris Davis, and Emily Le Coz were involved.

Digital design and illustration byAndrea Brunty.

Jim Sergent has graphics.

Jasper Colt, Hank Farr, and Chris Pietsch are pictured.

Social media, engagement and promotion: Nicole Gill Council.

The article originally appeared on USA TODAY.