The article was originally published at The Conversation.

Professor Jonti Horner, Senior Curator of Astronomy, Museums Victoria, is an astronomer.

Dust and debris left behind by comets and asteroids can be seen as Earth circles the sun. One of nature's most amazing spectacles is when debris gives birth to meteor showers.

Every year, the Earth travels a particular trail of debris and most meteor showers are recurring.

RECOMMENDED VIDEOS FOR YOU...

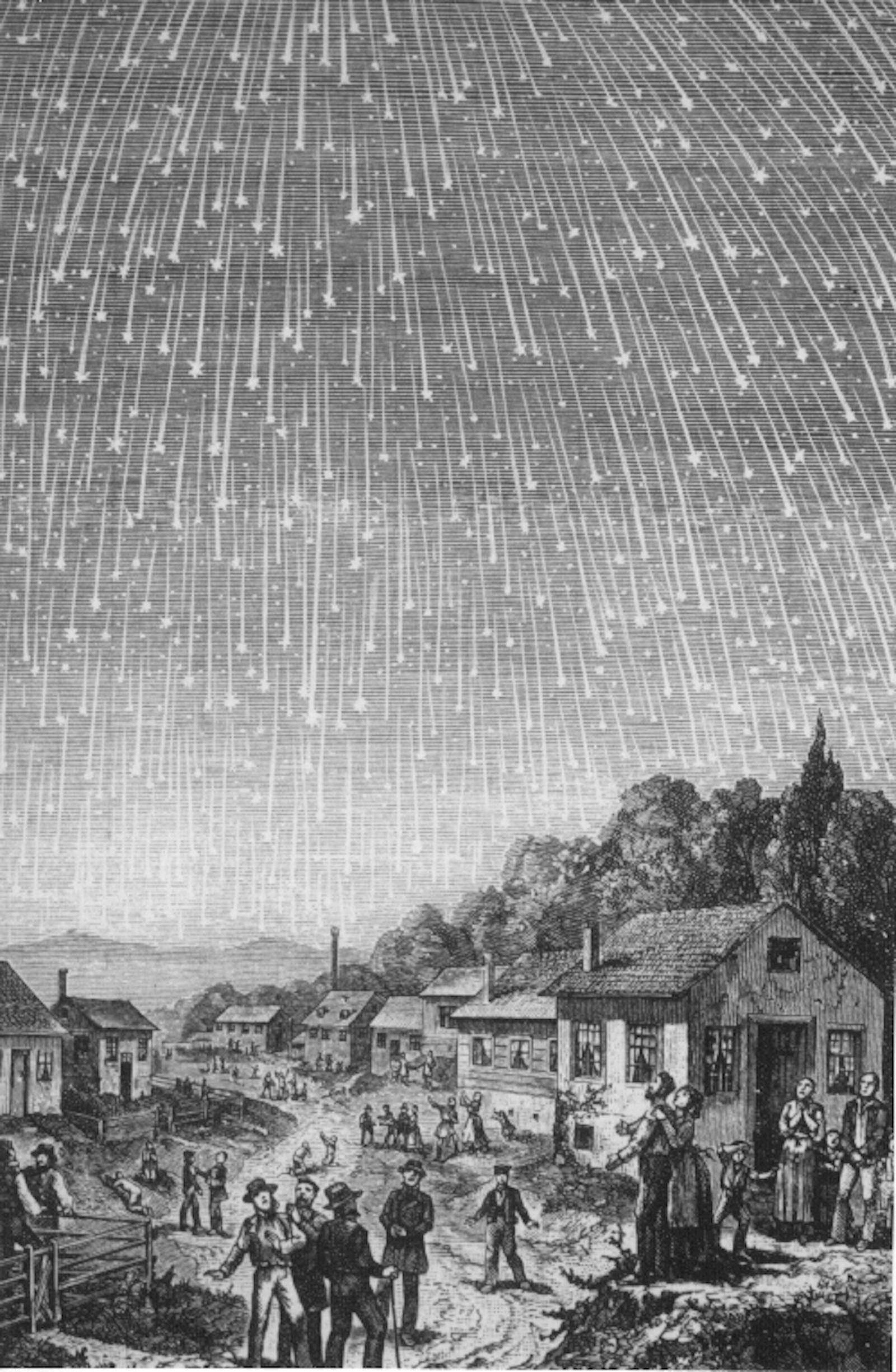

Occasionally, Earth runs through a dense clump of debris. Thousands of shooting stars streaking across the sky each hour are caused by this.

There is a chance that there will be a meteor storm this weekend. Astronomers are a little more cautious when it comes to websites that promise the most powerful storm in generations.

The story begins with a comet called 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 3. It was first spotted in 1930 and is responsible for a weak shower called the tau Herculids.

In 1995 comet SW 3 suddenly and unexpectedly brightened. There were a number of incidents over the course of a few months. Huge amounts of dust, gas, and debris were released by the comet.

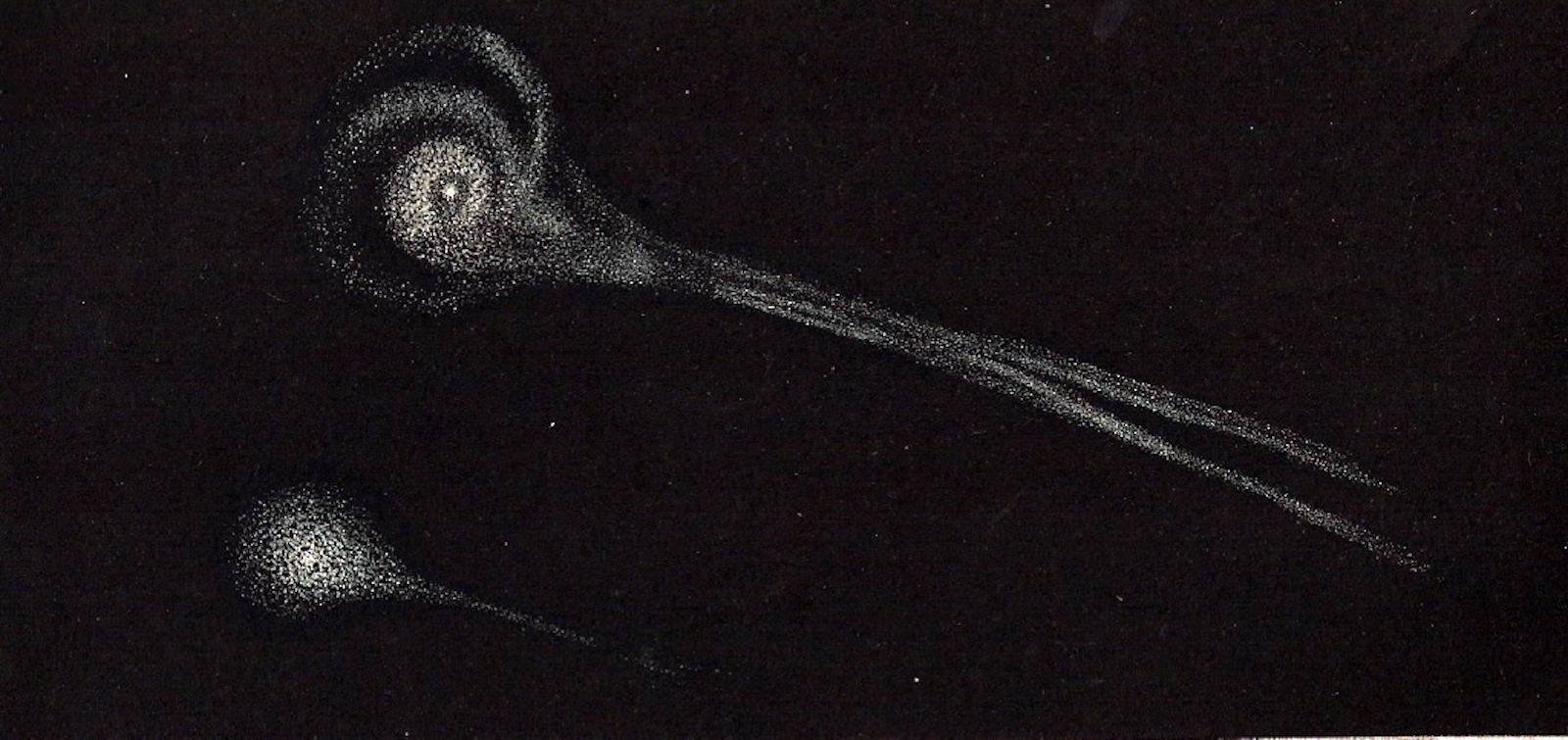

By 2006 comet SW 3 had disintegrated further, with several bright fragments accompanied by many smaller chunks.

At the end of May, Earth will cross comet SW 3.

The computer modelling shows that debris has been spreading out along the comet.

Is the debris long enough to reach Earth? It depends on how much debris was thrown as the comet fell apart. We can't see the small pieces of dust and debris until we run into them. How can we know what will happen next week?

Our understanding of meteor showers began 150 years ago with an event similar to SW 3.

In 1772, a comet called 3D/ Biela was discovered. It was a comet that came back every 6.6 years.

The comet began to act strange in 1846. Observers saw its head split in two, and some described a path of cometary matter between the pieces.

At the comet's next return in 1852, the two fragments were not predictable in their brightness.

The comet was not seen again.

In late November of 1872, a storm of meteorites hit the northern skies, with rates of more than 3,000 per hour.

The comet should have been two months earlier than when the Earth crossed 3D/ Biela. The first storm was weaker than the second, and the Earth once more encountered the comet's remains.

The two great meteor storms it produced served as a fitting wake, as 3D/ Biela had disintegrated into rubble.

A dying comet, falling apart before our eyes, and an associated shower, usually barely imperceptible against the background noise. Is history going to repeat itself with comet SW 3?

The main difference between the events of 1872 and this year is the timing of Earth crossing the cometary orbits. The comet was due after several months, but material was lagging behind where the comet would have been.

The comet is due to reach the crossing point before the encounter between Earth and SW 3. There needs to be a comet for a storm to occur.

The debris stream from SW 3 will fall just short, according to others, because it happens several months after the shower.

Observations of the comet shower next week will greatly improve our understanding of comet events.

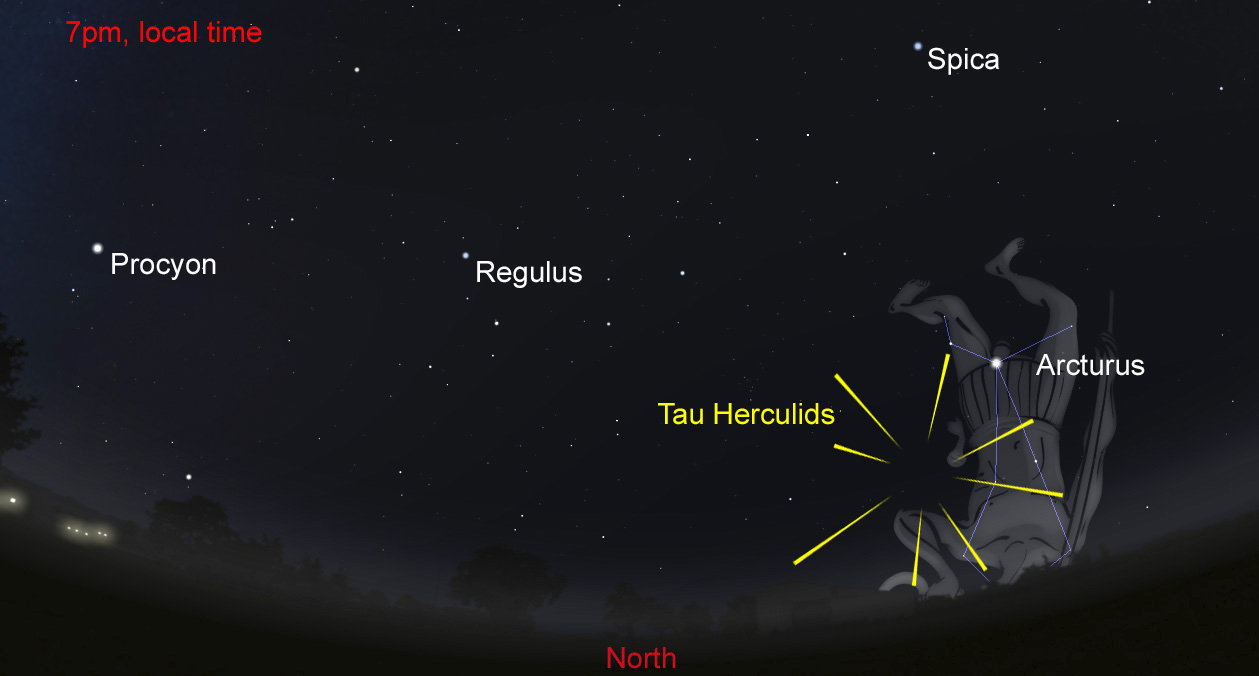

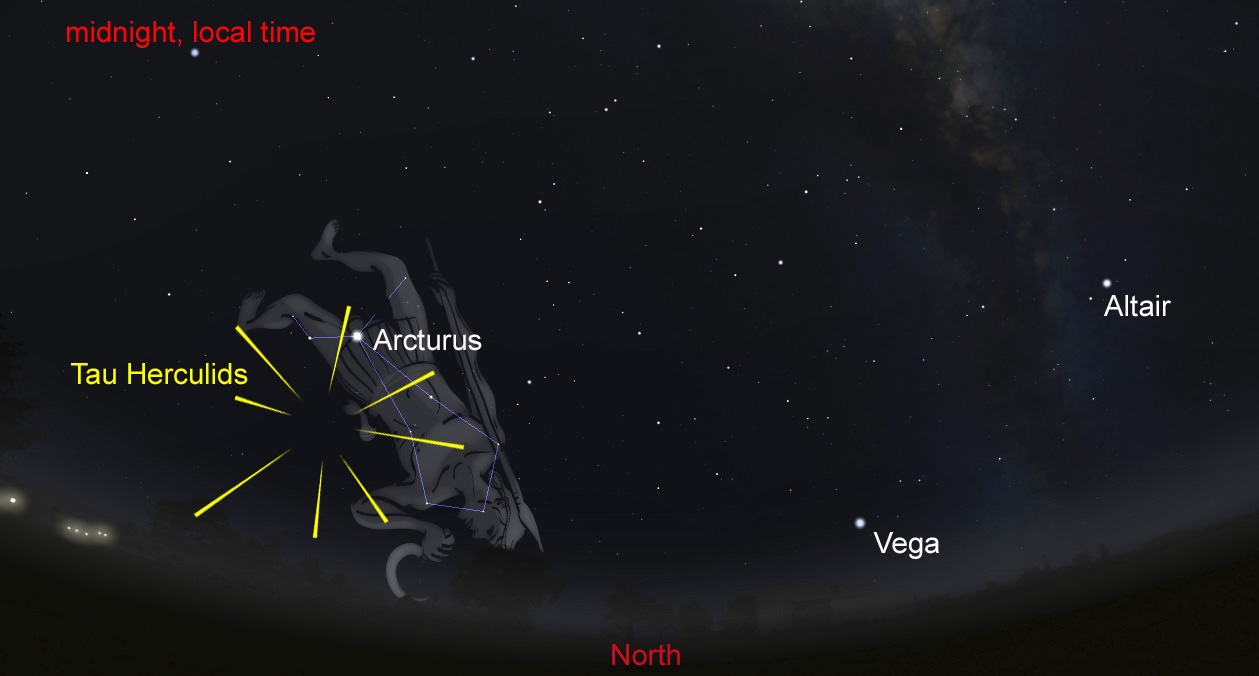

The Earth will cross SW 3 at about 2 a.m. May 31 is the opening day of the new tab. If the debris reaches far enough forward for Earth to see it, there is a chance of an eruption from the Herculids.

If there is one in Australia, the show will end before it is dark enough to see what is happening.

Observers in north and south America will have a seat.

They're more likely to see a moderate display of meteors than a big storm. This would be a great result, but it might be a little disappointing.

There is a chance that the shower will put on a spectacular display. Astronomers are on the move in case.

There is a small chance that any activity will last longer than expected. If you are in Australia, it is worth looking up on the evening of May 31 in order to see a fragment from a dying comet.

The comet has laid down many debris streams in the past.

During the early morning of May 31, Earth will cross debris from the comet. Earth will cross debris from the comet in 1897 at 8pm on May 31st.

The debris from those visits will spread out over time, and we expect only a few meteorites to grace our skies from those streams. The only way to know if we're wrong is to go out and see.

This article is free under a Creative Commons license. The original article can be found in the new tab.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates and become a part of the discussion on social media. The author's views are not necessarily those of the publisher.