The term "mete shower" is not a correct one. It creates a mental picture of shooting stars in the sky, but that is not the case.

Under a clear, dark sky, you can count three or four meteors per hour. On certain nights, that count can go as high as 15, 25, 50 per hour. The mainstream media usually tells the general public to expect something spectacular, but often they are left disappointed.

A meteorite storm is something else. In such cases, there will be meteors that will appear at rates of a thousand or more per hour and in a few rare cases, rates have been ten or even a hundred times greater than this!

How often do they occur? Here we provide a list of some of the best meteor displays from the late 18th century.

Dates and viewing advice are included in the guide.

If it wasn't for a throbbing head, this display of meteorites might have been missed. Alexander von Humboldt was a writer-scientist-explorer who chronicled what happened in the 18th and 19th centuries.

He and his colleague were located in Cuman, Venezuela. They had an encounter with a native who gave Bonpland a concussion.

Bonpland stepped outside at 2:30 a.m. on November 12 to enjoy the fresh air. He saw the most extraordinary, glowing meteors from the east and northeast. There was not a space in the heavens equal to three full moons which was not filled with bolides and falling stars.

Many of the shooting stars had a large nucleus, like Jupiter. Some falling stars could still be seen fifteen minutes after sunrise.

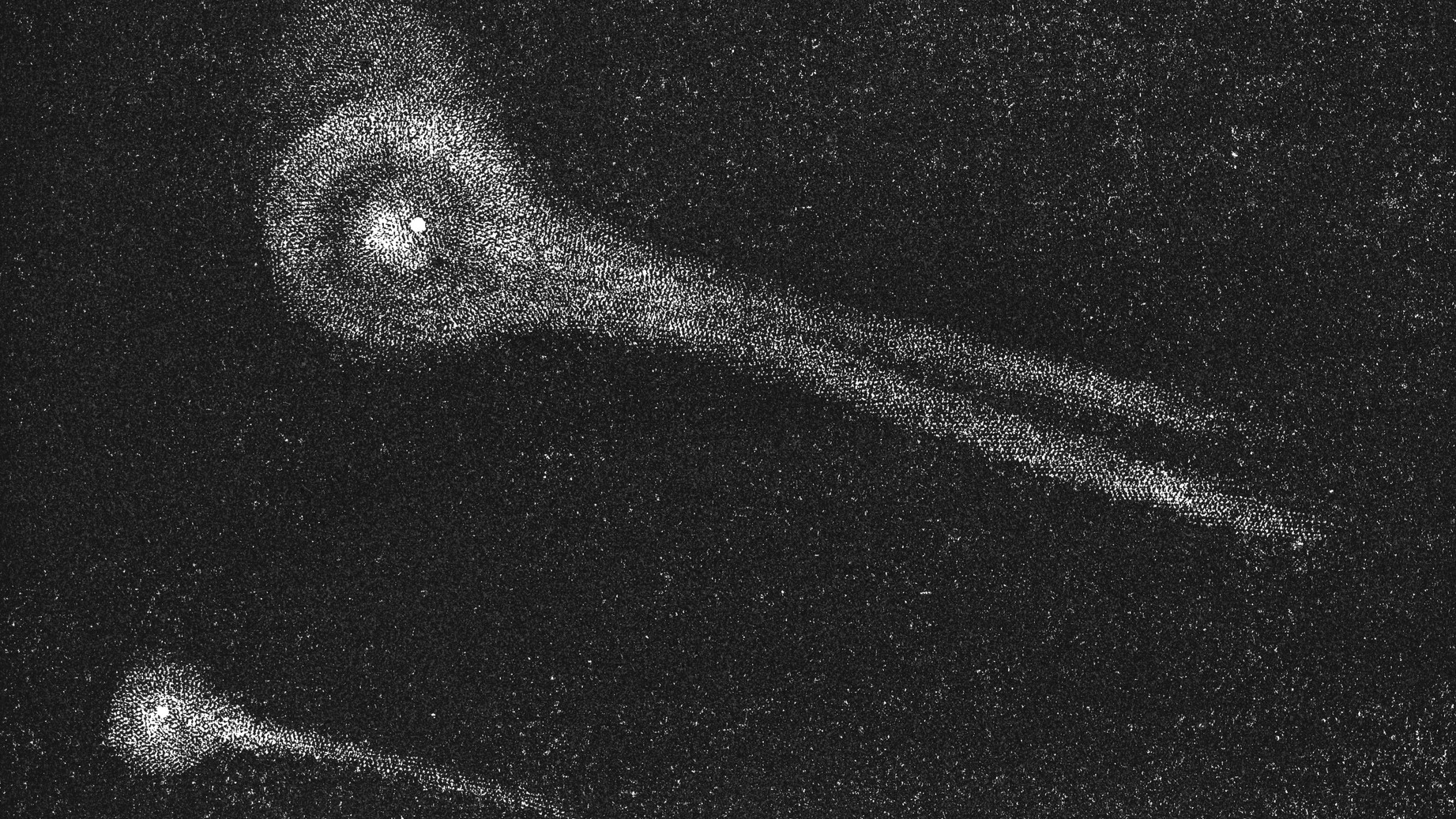

A fire alarm might have saved another spectacular storm of meteorites. The shower is barely a rich display, but it resembles a comet.

There are a number of records of meteor displays in China, Korea, and 687 B.C. The meteors were so bright that they looked like a shower of sky rockets.

You must see the impact craters.

One of the best showers on record. Estimates as high as 20 per second were made for stars falling in a snow storm. Many people fell on their knees to pray. The church bells were rung. People were afraid to stay at home.

The flashes faded away with the dawn. The sky in that direction was made to look like an umbrella by several observers who noticed a definite pattern to their motion. One of the most notable discoveries of the 19th century was the recognition of this point. Astronomers used to view shooting stars as too trivial a phenomenon to be studied, but now they can no longer ignore it. The beginning of meteor astronomy was marked by this amazing display.

Astronomers discovered that comets and meteor showers were connected, that comet particles released by comets along their orbits were encountered by the Earth, and that a display of meteors.

The comet responsible for the Leonid meteors was discovered in 1865 and is on the sun every 33 years. 33 years after their last great performance, another spectacular Leonid show would occur. It did happen, but not for America. Europe saw the fire.

It would be impossible to say how many thousands of meteors were seen, each one of which was bright enough to have elicited a note of admiration on any ordinary night.

The shower appeared over the United States. The rate was 1,500 per hour. It was the most brilliant seen in this country since the great shower of 1833, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory.

Since its last appearance six and a half years before, the comet has split in two. The comets traveled close together. One of the comets was very dim when it came back in 1852.

In 1858 and 1865 the comets were not seen again. As the Earth passed close to the comet, its dusty remnants began striking Earth's atmosphere. Four people in Moncalieri, Italy, described the meteors as resembling a real rain of fire, with them appearing at a rate of four per second. Some people said the meteors were falling at a high rate. The Leonids were described as being very faint. They became known as the "Andromedids" because they appeared near a spot on the sky where the constellations of Cassiopeia, Perseus and Andromeda converge.

The Andromedids made a return appearance 13 years after the storm of 1872, and Europe was once again favorably placed to view them. One well-known British meteor observer commented that as the night advanced, it became almost impossible to enumerate them, because they were falling so thickly.

The single observer rate in Italy and France was over 200 per minute. There was a report that a large number of meteors had brilliant phosphorescent trains, which continued to glow for several seconds after the meteors themselves had vanished.

The Earth passed through the wake of comet Giacobini-Zinner, causing a meteorite storm over Europe. Astronomers were completely off guard by this amazing display.

The New York Times reported that a veritable rain of falling stars was visible over the whole of France and Belgium between 7 and 9 o'clock. A peak rate of 480 per minute was recorded by an observer.

The meteors appeared to dart from the head of the constellation of Draco the Dragon and were referred to as "Draconid", though others called them "Giacobinids" after their parent comet. They were described as slow and yellow.

Astronomers were ready for the Draconids in 1946. The Earth seemed to be in a good position for a replay after the comet Giacobini-Zinner came back. Skywatchers were not disappointed despite a full moon.

Three of us tried to keep count, but after 500 we stopped. There was no quarter of the sky that wasn't lit up by the fireworks, and one observer from Chicago said that the bright meteors outshone Venus at her best, and showed colors of red, orange, and green.

The hourly rates ranged from as low as 3,000 to as high as 10,000.

They said that the Leonids were dead. Since 1867, they had not produced a storm like that. The comet and its trail of meteorites were thrown off course by Jupiter in 1898.

In 1899 and 1932, the expected rich displays didn't show up. When the Leonids put on a display in 1966, we were ready to give up. Some fireballs left trains that lasted up to 20 minutes, according to one observer from Kitt Peak Observatory. At the Table Mountain Observatory in California, observers saw a rain of meteorites turn into a hail of meteorites.

The sky over Europe and the Middle East was covered in a fusillade of Leonids. At a rate of one or two meteors per second, the roughly hour-long outburst peaked. It was not as big as the great storm of 1966, but it was still a spectacle. There was a high proportion of faint meteors in this display.

The setup was most unusual as two peaks were forecast. The first material shed by a comet favored North and Central America. The sky was bright with hourly rates as high as 1,300.

Concentrations of material released by the comet in 1699 and 1866 favored Australia and the Far East. The numbers peaked at around 4,200 per hour. Everyone was impressed by the many fireballs that left long-enduring trains lasting up to several minutes.

Again, a year with two peaks. Observers likened each outburst to a switch being turned on and off, and suddenly there were lots of meteors.

The first peak favored Europe; corrected single observer counts showed a rate of 2,300 per hour. The second peak favored North America with an hourly rate of about 2,700. A bright full moon and a lack of bright meteors is a disappointment.

New York's Hayden Planetarium has an instructor and guest lecturer named Joe Rao. He writes about astronomy for a number of publications. You can follow us on social media.