Some male wolf spiders seem to get lucky more often than others. The secret to their relationship? A new study led by the University of Nebraska says it is complicated.

Men across the animal kingdom have evolved many different ways to win over females.

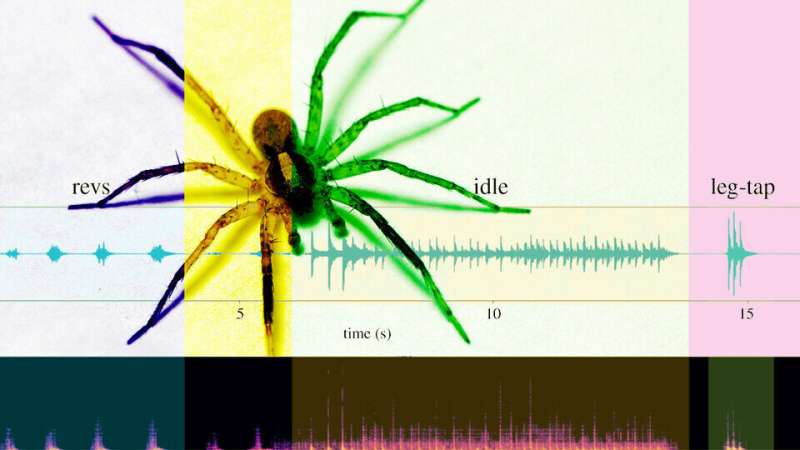

A male Schizocosa stridulans spider that encounters a receptive female will unleash an appendage-scraping, abdomen-quivering, leg-tapping performance that might last five minutes or 45. The sound of fingernails scratching wood, the sound of a mechanical ticker tape rattling, and the sound of flashes of percussion are all part of it.

The Nebraska-led team discovered that the nine S. stridulans males who were rewarded with sex also conjured more complex courtship signals. It was the first time that three different measures of complexity were used to describe whale vocalizations.

The lead author of the study said that females prefer to mate with males that can produce more complex signals.

In the lab, a female S. stridulans will deposit silk to let males know that she is ready for love. A male usually opens by tasting her silk and moving his pedipalps, a pair of sensory appendages near the mouth that can hold and expel sperm. Then come one or two leg-taps, the male drumming his forelegs prestissimo, with blinding speed, followed by a continual bassline of tremors in his abdomen that transmit through his eight legs to the ground and ultimately the female, which feels them rather.

Such a showy performance can take its toll.

He said that they wanted to understand why the males use complex signals instead of simple ones, because they take a lot of energy and time to produce.

In pursuit of answers, Choi decided to review an experiment that his adviser, Eileen Hebets, had actually led years earlier. Hebets team would deposit a female S. stridulans into a soundproof chamber before introducing a male. The team used a camera and a laser vibrometer to record the courting. By shining the laser down at a piece of reflective tape stuck to the filter paper, the team captured every last signal that a male sent a female. The camera caught any visual flourishes.

The previous studies mostly looked at parts of the whole. He was interested in the complexity itself. No arachnologist had thought to use any of the methods developed by computer scientists. The number and recurrence of distinct patterns within a sequence of signals is measured by one, which has served as a basis for data-compression algorithms. The average amount of information conveyed by a given signal is quantified.

Hebets, Charles Bessey Professor of biological sciences at Nebraska, has been studying complex signaling for 25 years. We would look at each mode independently. We started to look at inter-signal interactions but still treated each sensory component as a separate entity.

We are at the point, with some really talented people who have quantitative skills, of coming up with computational ways to look at how all of these things might interact, and how the entire package might be important in ways that we would never understand.

Regardless of which of the three statistical analyses he applied, Choi found that the nine successful males produced more complicated vibratory signals than the 35 males that were turned down.

The findings suggested that males may have been rewarded for paying attention as well. The signal complexity of the males was increased even further with heavier females, which are more likely to birth and rear a large, healthy cluster of spiderlings. The successful males tended to up the complexity of their signaling as their courting went on, indicating that they may have been responding to signs of interest from the females.

Hebets said that people don't appreciate that signalers are paying attention to the receiver.

People who work on other animal groups are often surprised when they see stories of spiders engaging in sophisticated behaviors. We have found this in several studies, and it shows that spiders are just as smart as any other animal when it comes to communication.

Why would a female prefer a male that can, or is at least willing to, court her with a more complex signal?

The complexity points to a quality in a male that a female would like to see passed along to her offspring. The team did not find a connection between the physical prowess of a male and the complexity of his signaling. The findings are in line with an earlier study that suggested females might be looking for two skills needed to coordinate a complicated courting.

Hebets said that females aren't necessarily looking for the biggest male or the strongest male.

She said that it is possible that female S. stridulans prefer males that process complex signals. Another familiar explanation? Like humans, the wolf spiders can grow bored with the status quo.

There are a lot of studies that show that animals prefer novelty.

The findings were detailed in the journal.

More information: Noori Choi et al, Increased signal complexity is associated with increased mating success, Biology Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2022.0052 Citation: Male wolf spiders get luckier following complex courtships (2022, May 27) retrieved 27 May 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-05-male-wolf-spiders-luckier-complex.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.