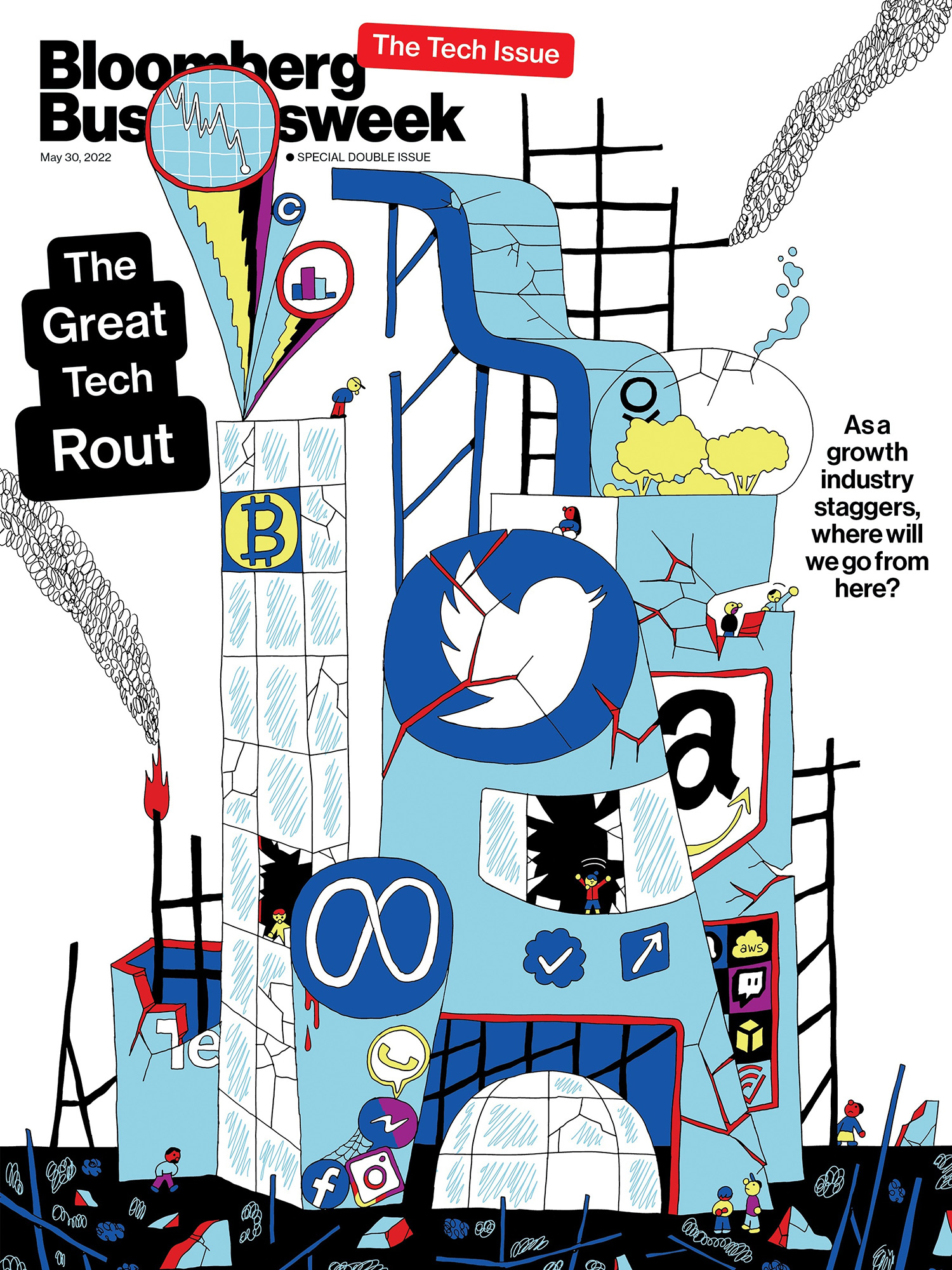

Silicon Valley has been trying to find a balance between wealth creation and moneymaking over the past 50 years. Wealth creation is the act of invention and long-term business building. The rising tide lifts the boats of employees, shareholders, and everyone else. The hunt for a quick buck is the base impulse. When short-term profiteering takes precedence over the development of stable companies that can create cool stuff, the technology industry and its risk-happy patrons have learned. Here we are again. The years of wildly inflated valuations, pyramid schemes, and naked opportunism have led to the bust of 2022.

The tech-laden S&P 500 has lost 20% of its value so far this year. The worst-hit have been Amazon.com, Meta, and Shopify. The boom times of the last decade are over, according to the partners at the venture capital firm Lightspeed Venture Partners.

VC high priests often argue that the downturns are macroeconomic acts of God, like a 100 year storm or a 15-year storm, and that no need for anyone to moderate their selfishness or learn other important lessons. Two decades of low interest rates cast tech companies as attractive investments, sending a flood of capital from public markets their way, according to the argument. Competition to back the most promising startups drove valuations to unsustainable heights until a confluence of bad news brought it all crashing down. It is comforting to blame the world. The industry is facing up to the compounding impact of its bad decisions, which is the truer explanation.

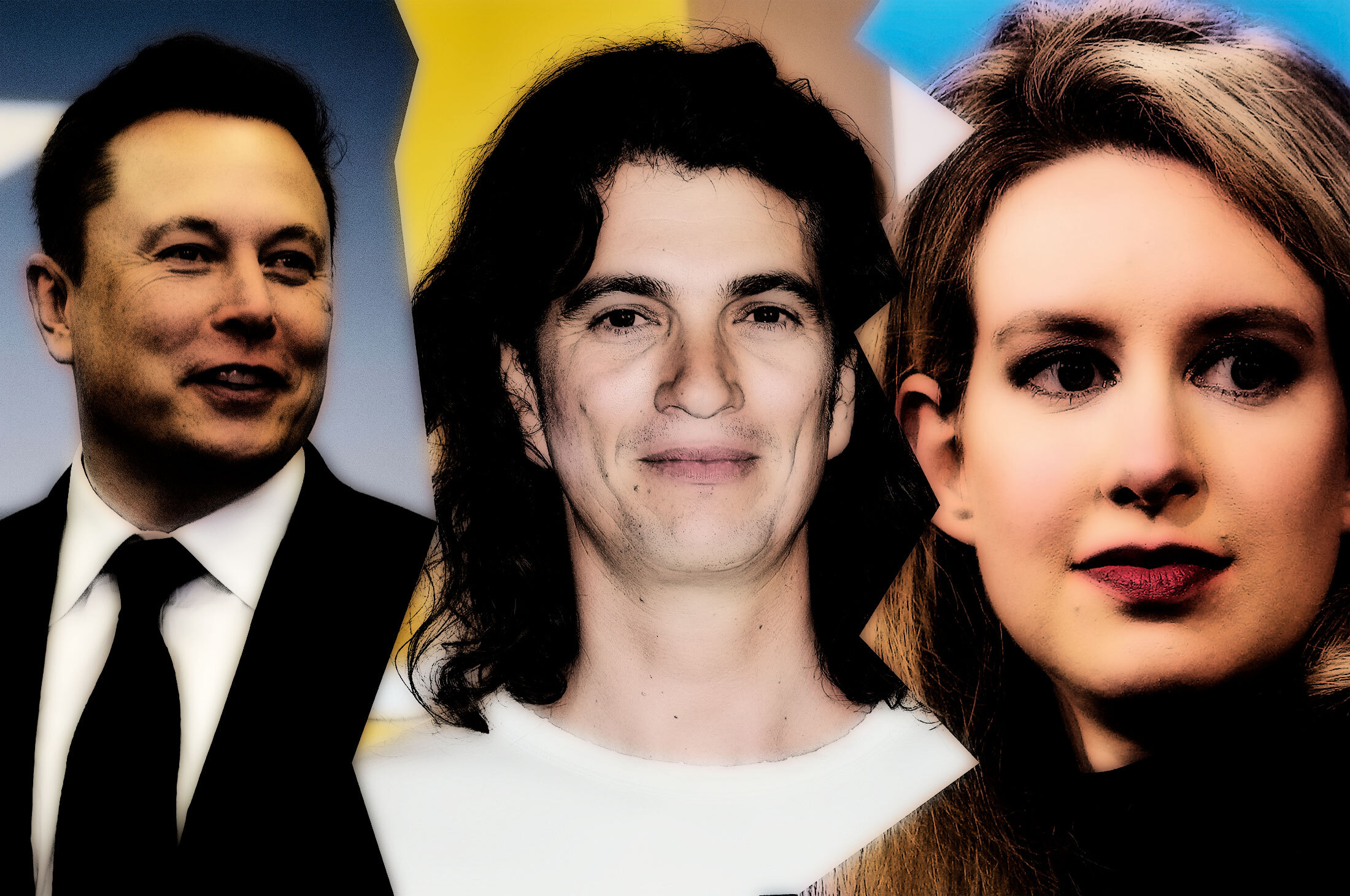

There are two things that motivate venture capitalists: a paralyzing fear of missing the next big thing and greed. A decade ago, new companies began leaving startup schools such as Y Combinator in order to be valued in the millions of dollars before they ever earn a cent. To attract the most promising startups, certain VC firms, notably the one with the best reputation, like the one with the best reputation, like the one with the best reputation, like the one with the best reputation, like the one with the best reputation, like the one with the best reputation The blood-testing disaster Theranos and the office-sharing supernova WeWork led to some bingeworthy TV but didn't prompt a serious retreat from this Monopoly-money mindset. There was so much money available at every stage and everywhere you looked, that VC firms and their new rivals continued jockeying to invest and bid up prices every step of the way.

Many founders took all the money they could get. Some major startups raised multiple rounds of funding per year, with the founders selling portions of their personal shares for early cash, and using risky financing schemes such as convertible notes, where investors could buy stakes even as they were ignorant about future valuations. The investors who resisted these risks had to weigh their options against the fear of missing out.

The oversight built into the initial public offering process was able to protect the wider markets from WeWork's IPO proposal, which collapsed after universal ridicule of its financial disclosures. Private companies were able to find a way to use special purpose acquisition companies. The offerings cleared the way for businesses including lender SoFi, space companies Rocket Lab and Virgin Galactic, pet-product subscription service Bark, and Grab. Yelena Dunaevsky, an attorney who specializes in SPACs at the law firm Woodruff Sawyer, says that too many people have piled in and taken the SPAC brand away from it.

The Valley, its industry counterparts around the world, and a lot of other people to the risks that come with its ferocious gambling have been blinded by this bad behavior. Digital currencies, shady exchanges, and virtual assets were piled into by speculators. The pitch for Web3 sounds like wealth creation, decentralizing the internet, and creating a set of tools that restore power to the people, and free them from dependence on tech giants and traditional banks. The majority of thecryptocurrencies to date involve quick cashouts that leave the other parties with a lot of funny money. TerraUSD, which recently collapsed in value after suffering the equivalent of a bank run, is one of the initial coin offerings. The performance of the major cryptocurrencies has fallen since the start of the year.

During the Super Bowl, NBC broadcast ads starring Larry David, Matt Damon, and LeBron James, and the mania seemed to reach its peak. The Super Bowl ads gave techies a taste of what it was like to be in the dot-com bubble.

The last shock on this level has been so long since the last downturn, the Bust of 2022, feels oddly unfamiliar. The previous boom cycles lasted about eight years. The pressure has been building on this volcano for more than a decade. In the year of 2021, US tech startups raised three times the amount they raised in 2000, and the bust is global in a way that previous industry downturns haven't been. The Communist Party's campaign to curb the power of tech giants in China has caused stock prices and valuations in the UK to fall.

The tech world feels more political and divided than it has in the past, as though some of the same tools that caused political divisions elsewhere have now been trained inward. There is no better example of this than in Musk's acquisition of the social media site. Over the past month, Musk has declared his fealty to the Republican Party and accused people who are less likely to call someone a pedo guy of being victims of a woke mind virus.

This is new. Steve Jobs and Bill Gates got a lot of respect from politicians, but they needed customers from both sides of the aisle. Money has mostly spackled together for a generation, and now the tech monolith is crumbling. Donald Trump forced tech companies to side with him on issues like immigration, free expression, and the proposed ban of the video-sharing site TikTok. Today's startup founders and funders still have to reckon with the politics of Musk, Peter Thiel, and others on issues like college-loan relief, taxation, and who should shut up. The acrimony has led to a wave of high-profile defections from Silicon Valley to Miami and Austin, cities promising an even more laissez-faire home base. The Bay Area is the center of its world and the industry can't agree on whether it is or isn't.

We haven't seen any real carnage yet.

Regular investors and rank-and-file employees are likely to suffer in this downturn. The founders and institutional investors who sold their shares during the good times earned hefty management fees. The investors who are sitting on a record $300 billion in uninvested capital will still earn management fees regardless of the market's performance.

More than 13,000 tech workers have been laid off around the world since the beginning of April, according to a tracking site. Elad Gil, a venture capitalist, says there will be more to come if the downturn drags on. A lot of people are either uncertain or in denial.

In any market downturn denial is a ticket to catastrophe. This edition of the Tech Issue is here to clear that up. We will guide you through the peaks and valleys of the technology landscape that is left standing, including Facebook's failure to beat TikTok at its own game, and the costs of Google's browser supremacy.

There is a new kind of online prediction market and the controversial popularity of polygenic risk scoring, which aims to help parents who are going to have in vitro fertilization lower their offspring's risk of cancer, diabetes, and other diseases. Even in a new downturn, a lot of industry veterans are still optimistic. The ones that don't will be fine.

The mathematician whose hack upended defi won't give back his millions.