The Solar Orbiter made its closest approach to the Sun on March 26th. It was one-third the distance from Earth to the Sun. It was hot but worth it.

New images from the close approach are helping to build an understanding of the Sun and its heliosphere.

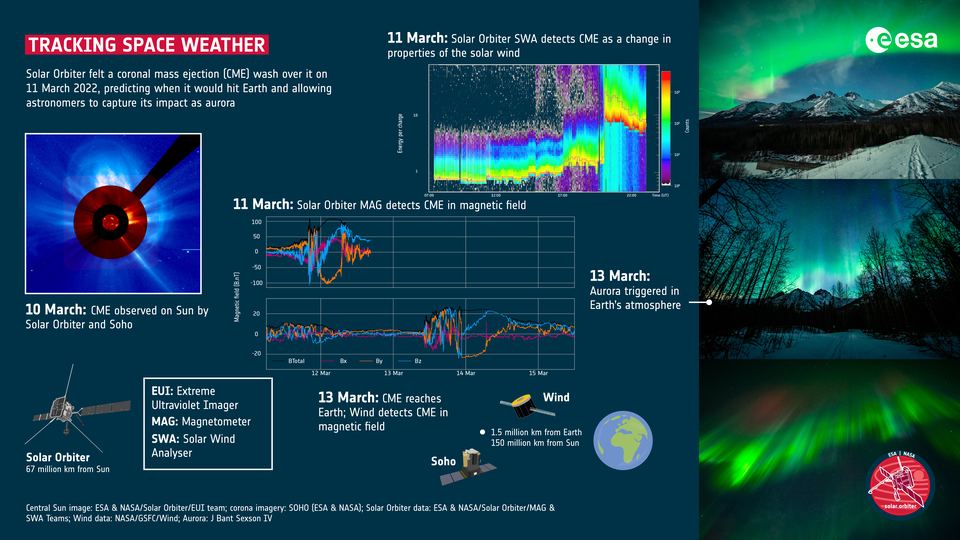

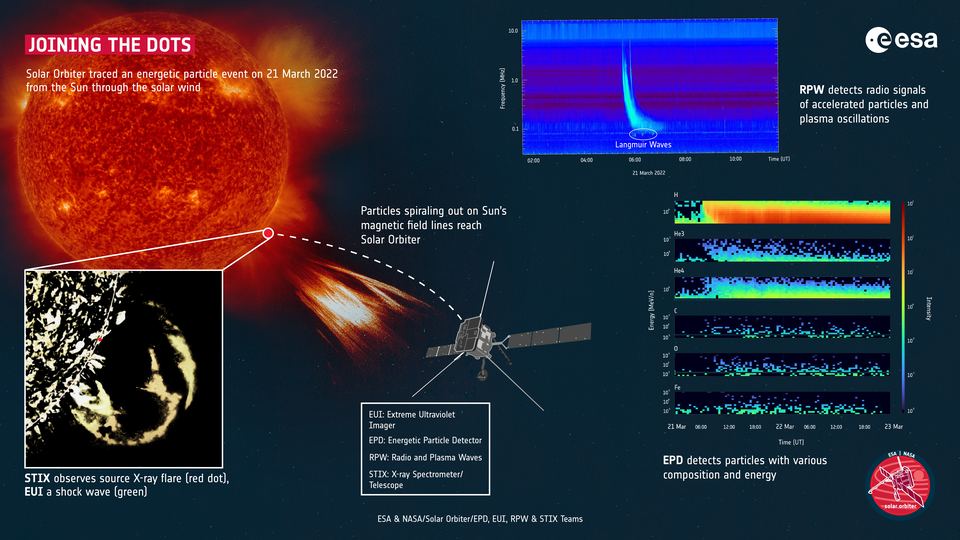

The most complex scientific laboratory ever sent to the Sun is the Solar Orbiter. It has a number of instruments, including a Magnetometer, an Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, and a Solar Wind Plasma Analyzer. It can observe solar events in many ways.

Getting as close to the Sun as possible benefits the craft. The Solar Orbiter is hot when close approaches. The heat shield is the first line of defence. It is a multi-layer titanium device mounted on a honeycomb aluminum support with carbon fibre skins. There are 28 layers of insulation between the spaceship and its body. The heat shield reached 500 Celsius.

The Solar Orbiter was protected from the heat. The images and videos are engaging even though scientists need more time to understand it. One of the Sun's features caught the attention of everyone.

The Sun put on a show during the Solar Orbiter's approach thanks to a bit of luck. There were solar flares and a coronal mass ejection. Scientists used the Solar Orbiter's remote sensors to forecast when the CME would reach Earth. They released their forecast on social media and Earthly observers were ready to view the resulting Aurora. The graphic was released to explain how that happened.

The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, the Metis coronagraph, and the Solar Orbiter Heliospheric Imager are some of the instruments that have images of the flares.

The video is explained in an Infographic created by the ESA.

The highest-resolution image of the Sun's south pole was provided by the Orbiter.

The Sun's magnetic fields are what scientists are interested in. The magnetic fields on the Sun's surface create active regions that are swallowed by the Sun again. Scientists believe that they act as seeds for the next solar activity. The Sun's south pole should help researchers understand how this all works.

The Sun's south pole has a lot of magnetic loops rising from its interior. Particles have difficulty crossing closed magnetic field lines. The particles become trapped and emit extreme ultraviolet radiation, which the Solar Orbiter is poised to capture.

The Sun's magnetic field lines are open in the darker regions of the video. gasses can escape into space from the darker regions, instead of being closed to particles. That causes solar wind.

There was a solar flare on March 2nd. The flare was captured by the EUI and the X-ray Spectrometer/Telescope instruments as solar atmospheric gases reached temperatures of one million degrees C.

The lower-energy X-rays are shown in red and the higher-energy X-rays are shown in blue.

There is more to come from the Solar Orbiter. For the next four years, Venus will be visited by the spacecraft. It will increase its inclination and give it more direct views of the Sun's poles. The start of the mission will be marked by it being orbitally inclined at 24 degrees.

Scientists will be able to see the poles with high-latitude observations. The views are important to disentangling the Sun. The Sun's 11-year cycles are a mystery.

The quality of the data from the first perihelion was very good. We are going to be busy.