Pallab Ghosh is a science correspondent.

Image source, JIC

Image source, JICA bill will be introduced to Parliament on Wednesday that will allow genetically edited plants and animals to be grown and raised in England.

The new legislation would only apply to plants and would not apply to other products.

The technology is not being used because of European Union rules. The UK can now set its own rules.

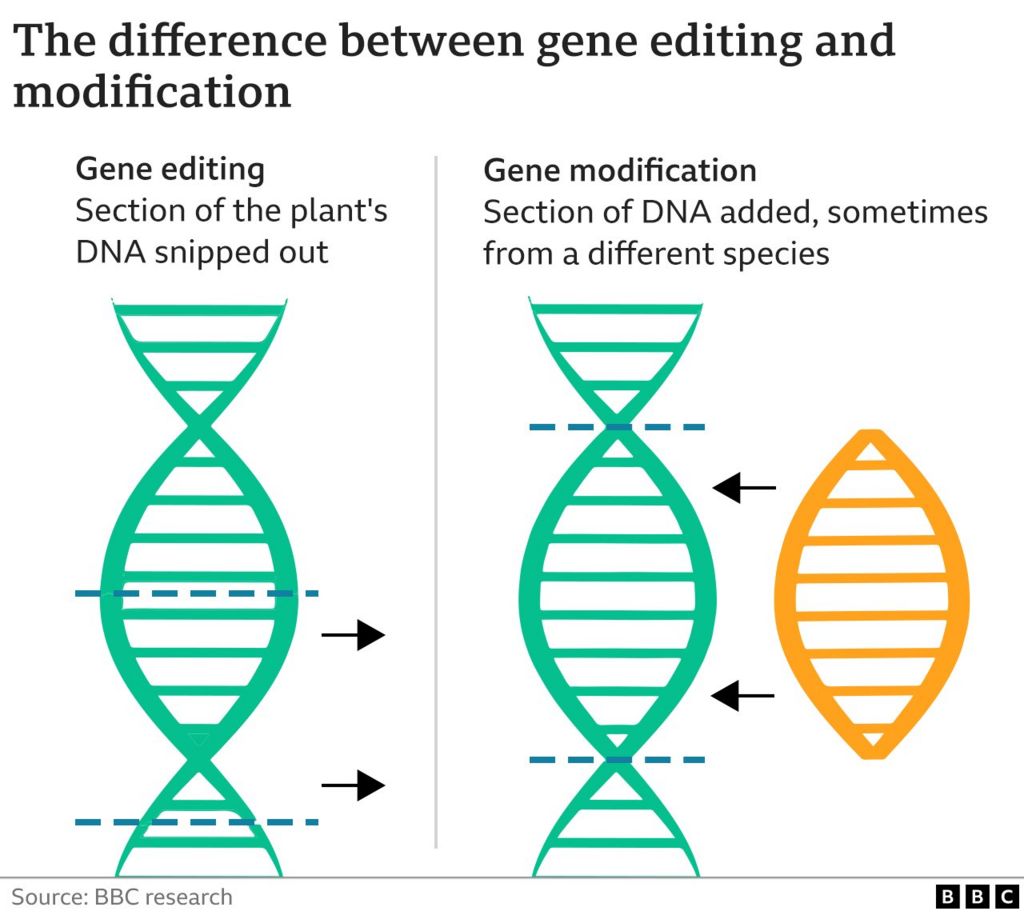

Gene editing uses a small piece of DNA to switch genes on and off.

It can lead to the production of varieties that could be produced using traditional cross-breeding methods.

The new regulations take away much needed scrutiny according to critics such as Liz O'Neill, who is director of GM Freeze.

She said that the need for transparency and an independent risk assessment have been removed.

Many researchers wanted the government to legislate for the commercial use of GM crops, but ministers decided to be more cautious.

Adding genes is a part of the older process of GM. Both technologies have been shown to be safe in scientific studies, and GM crops have been grown outside of the EU for 25 years.

Gene editing will lead to crops that are resistant to pests and diseases and more resistant to climate change, according to the government. The aim is to increase productivity.

The government hopes that relaxing the law will lead to the creation of new foods and businesses in the UK.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs held a public consultation after the UK left the EU. George Eustice, the Environment Secretary, believes that there was enough support for the introduction ofprecision breeding.

According to Defra polling, 57 per cent of people think the use of GE crops is acceptable, while 32 per cent think it is unacceptable. Support went up to 70 per cent for some applications, such as reduced use of pesticides.

There was less support for the use of gene editing on animals. Gene editing can be used to make livestock resistant to disease, which will benefit both the animals and the farmers. The technology could be used to boost farm productivity at the expense of animal welfare.

The bill wouldn't allow gene-edited animals immediately, but it would give ministers the power to introduce it when they were satisfied that the regulation was sufficient to ensure that livestock wouldn't suffer.

Image source, Acceligen

Image source, AcceligenLast month, the rules governing research into gene-edited plants were relaxed because they didn't require new laws to be passed.

The first seeds approved by the new process were planted last week by Prof. Napier.

He said that society will benefit from new discoveries of better crops and more nutrition.

Image source, ROTHAMSTED RESEARCH

Image source, ROTHAMSTED RESEARCHJo Lewis, policy director of the organic food body the Soil Association, was critical of the bill, saying that it avoided dealing with the transformation needed in our food and farming system for true security and resilience.

The government prioritised unpopular technologies over the real issues of healthy diet, a lack of crop diversity, and the decline in beneficial insects who can eat pests.

He said that history had shown that the predecessor of GM, gene editing, only benefits a small group of businesses with a rise in crop patents and profitable weeds.

David Exwood is the vice president of the National Farmers Union.

This science-based legislative change has the potential to offer a number of benefits to UK food production and to the environment and will provide farmers and growers with another tool in the toolbox as we look to overcome the challenges of feeding an ever-growing population while tackling the climate crisis.