Janek is a technology of business reporter.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesThe war in Ukraine has changed Germany's energy policy.

The nation buys 25% of its oil and 40% of its gas from Russia.

Germany is moving as fast as possible to end that relationship, but it will take time, the country's finance minister recently said.

Veronika Grimm is an economics professor at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, and one of Germany's three special advisors to the federal government.

She says that we need to decarbonise our energy sources faster than initially planned. Ms Grimm wants the nation to use hydrogen more.

Hydrogen can replace natural gas in industrial processes and power fuel cells in trucks, trains, ships or planes that emit nothing but water.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesDozens of countries have published national hydrogen strategies or are about to, according to the International Energy Agency.

It is not clear yet if large-scale use of hydrogen can be made viable.

In the 1970s and 1990s, there was similar excitement after two oil crises. Both ended up petering out. Is today's hype any different?

The answer is dependent on who you ask. Environmental groups caution that hydrogen can't be used as a primary fuel. It has to be made in two ways, each marked by a colour code.

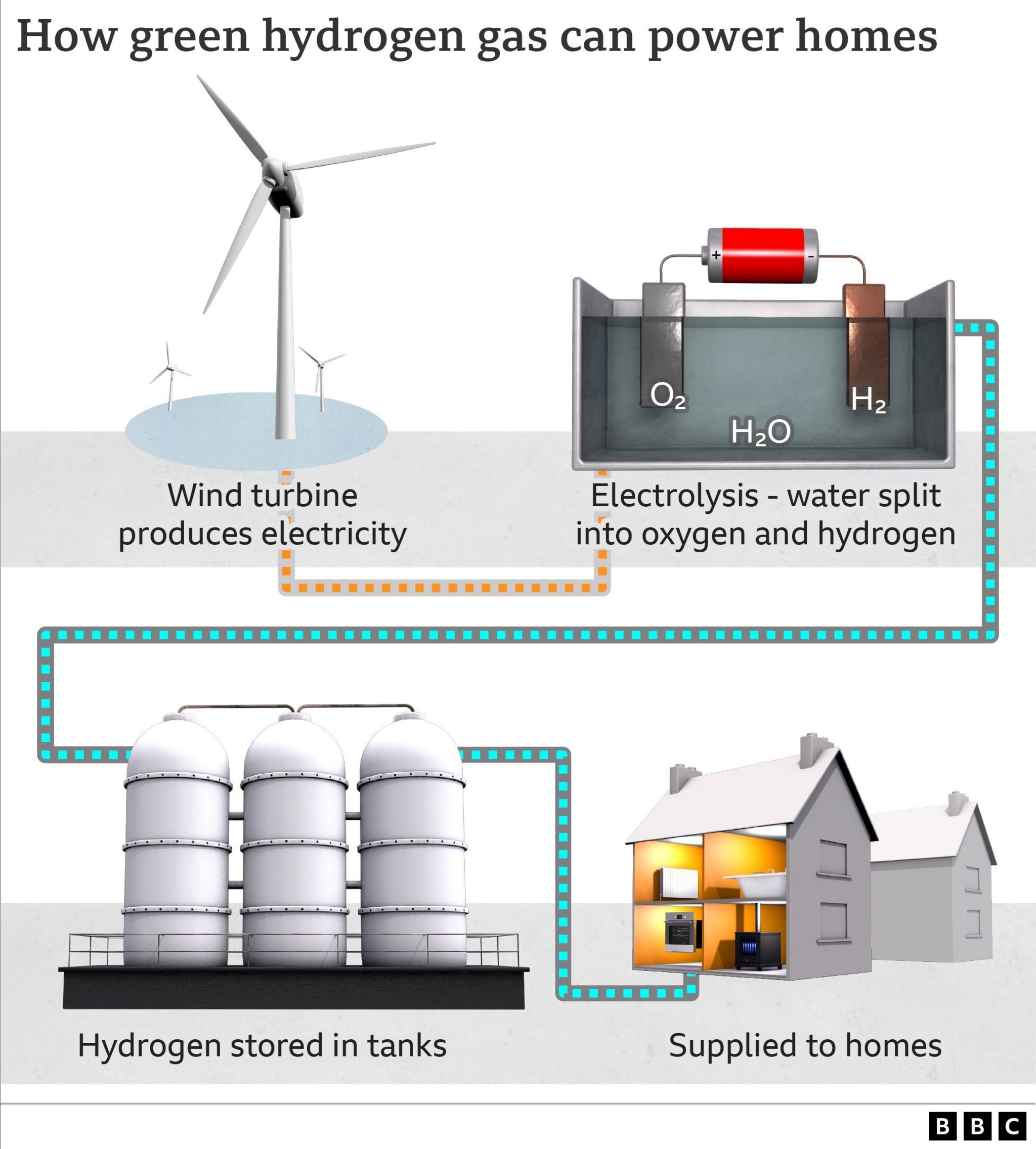

Electricity from renewable power is used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. The machines and electricity are expensive.

According to the IEA, emission-free hydrogen makes up only 0.03% of global hydrogen production.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesGrey hydrogen is derived from natural gas or oil and can be up to five times cheaper. If natural gas were directly burned, about 50% more CO2 would be emitted.

Blue hydrogen is a related technique. The same process is used, but it captures less of the carbon emissions in production for re-use or storage. The method triples the cost. Only 0.7% of the hydrogen produced in the world is blue.

The global production of hydrogen emits more CO2 than the entire country of France.

How countries decide to produce hydrogen will be the most important factor.

Most sun-baked nations bet on solar power, while France uses nuclear energy.

China invests in green alternatives and cherishes cheap grey hydrogen from coal and gas.

The US, Canada, UK, Netherlands, and Norway are leading the push for blue hydrogen, by injecting captured carbon into oil and gas fields for long-term storage.

The picture is not as clear in Germany.

The hydrogen strategy of Germany was used as a red herring by the government to hide its own failures in the energy transition.

He thinks solar and wind power should have been expanded more quickly.

The three parties in government, the three responsible ministries and the hydrogen council all argue about whether to focus on green hydrogen or the blue alternative to temporarily bridge the gap in limited supply.

Ms Grimm is a member of the hydrogen council that favors a multi-colour mix.

She argues that accepting blue hydrogen will help create the supply that we need for a budding industry.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesIn January, Economy Minister Robert Habeck announced an ambitious push for renewables and a doubling of the two-year old target for domestic production of green hydrogen to rise by a factor of 150.

That target is larger than France's goal of 6.5GW, and represents a quarter of the EU's goal.

Germany is looking to source hydrogen from abroad.

The head of the German Energy Agency says Germany has sped up international negotiations to buy hydrogen.

There are plans to make hydrogen using solar power in Spain and Portugal.

Mr Habeck is in a hurry. He traveled to Norway to agree on a feasibility study for the construction of a hydrogen line, went to Qatar to sign an energy partnership agreement, and then went to the United Arab Emirates to sign five cooperation agreements.

The first deliveries are expected later this year.

Mr Habeck has a hydrogen radar that has countries on it.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesMr Quaschning does not agree with Mr Habeck about the need to import hydrogen.

Some of the original energy used in the supply chain is desalinating sea water to get fresh water as raw material, liquification for shipping, and re-conversion of hydrogen into electricity.

Mr Quaschning says that these steps would eat up 70% of the electricity produced in the desert.

Even though a solar panel in the desert produces 80% more electricity than one in Germany, the losses on the way are so big that it would be twice as effective to directly produce solar power in Germany.

Hydrogen is referred to as the champagne of the energy transition due to its high cost. Who will get the first sip?

Felix Matthes, an energy expert at the ko-Institut, a think tank, and member of Germany, says that it is crucial that we allocate hydrogen only to those industries where direct electrification is not possible.

He argues that it should be used in the production of steel, chemicals and glass.

Shipping, long distance truck transport, as well as planes for medium or long distances could be the next sectors. He says that other uses in cars and heating are impractical.

Mr Matthe said that Mr Habeck's new push for renewables will create a greater need to balance our electricity supply, which hydrogen could do with the production of hydrogen on sunny, windy days as large-scale storage for cloudy winter days.

Germany is under pressure to stop spending so much on Russian energy.

Many will be hoping that hydrogen will help ease the transition.