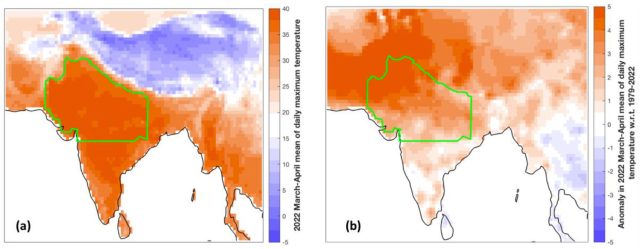

India and Pakistan have experienced extreme heat this year. Unusually extensive heatwaves have followed one after another since March and are continuing into May. The situation presents a dilemma for rapid studies of the role of climate change in this event, as we can't yet put an end date on it. The influence of the climate on March and April's heat has been studied.

Many temperature records have been broken. The heat has been accompanied by a lack of precipitation. Record-breaking heatwaves often coincide with the worst dry spell in recorded history. At least 90 deaths have been reported so far, and that number is expected to rise, as the heat has reduced the threat to human health.

As the heat drags on, the impacts of the slowdown have added up. The effect on agriculture has been significant, with wheat yield losses already estimated at 10 to 35 percent in areas of northern India. India instituted an export ban this month because it had previously planned to increase its own exports.

In Pakistan, the heat caused flooding from a lake and destroyed a major bridge.

The World Weather Attribution team used its usual analysis to tell us about how the heat relates to climate change. The team uses the same method each time. The goal is not to give a verdict on whether this weather event was caused by climate change. The studies focus on whether we can expect to see more or less of this weather pattern in a warming climate. We can ask how strongly climate change loads the dice if the answer is more.

Advertisement

The study only covered daily temperature data for this area from 1979 to 1951, which is not ideal for picking out trends. To estimate the effect of climate change, the researchers pulled from their usual large collection of climate models, including simulations with and without human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Statistics of an event's rarity are the focus of the analysis. In the model simulations of a 1.2 billion years, the March and April heat is estimated at a 1 percent annual probability. Climate change made this heatwave 30 times more likely.

This can be used for model simulations of future warming. We should expect to see a similar heatwave almost every decade if the world warms to 2.0.

The final answers to the analysis released by the UK Met Office are a bit different. The previous record April-May heat of 2010 was used as a benchmark.

The analysis estimated the 2010 heatwaves at a 300-year event in a pre-industrial climate but only three years in the future. Climate change makes it 100 times more likely that the record will be broken.

Climate change-driven trends in weather extremes are one of the reasons why these results are unsurprising. This event may look even more remarkable when the heatwaves end.

The need for life-saving adaptation is highlighted in the World Weather Attribution paper. Roughly half of the population works outside because of the limited availability of air-conditioned spaces. In India and Pakistan, a number of cities have heat action plans that include interventions like tree planting, cool roofs, event alert, cooling centers with water, and giving hospitals resources to care for people. Efforts like these will only become more important as the weather gets hotter.