The Ashaninka Indigenous people of the western Amazon basin were persuaded by a premonition to embark on a great traditional expedition. More than 200 Ashaninka from the Sawawo and Apiwtxa villages in Brazil and the Amnia River in Peru were taken to the pristine deep in the forest to enjoy peace and tranquility. The river waters were clear and safe for children to splash in and the night sky was full of stars for the spirit to soar in. The Ashaninka spent a week camping, hunting, fishing, sharing stories, and imbibing all the joy, beauty, and serenity they could.

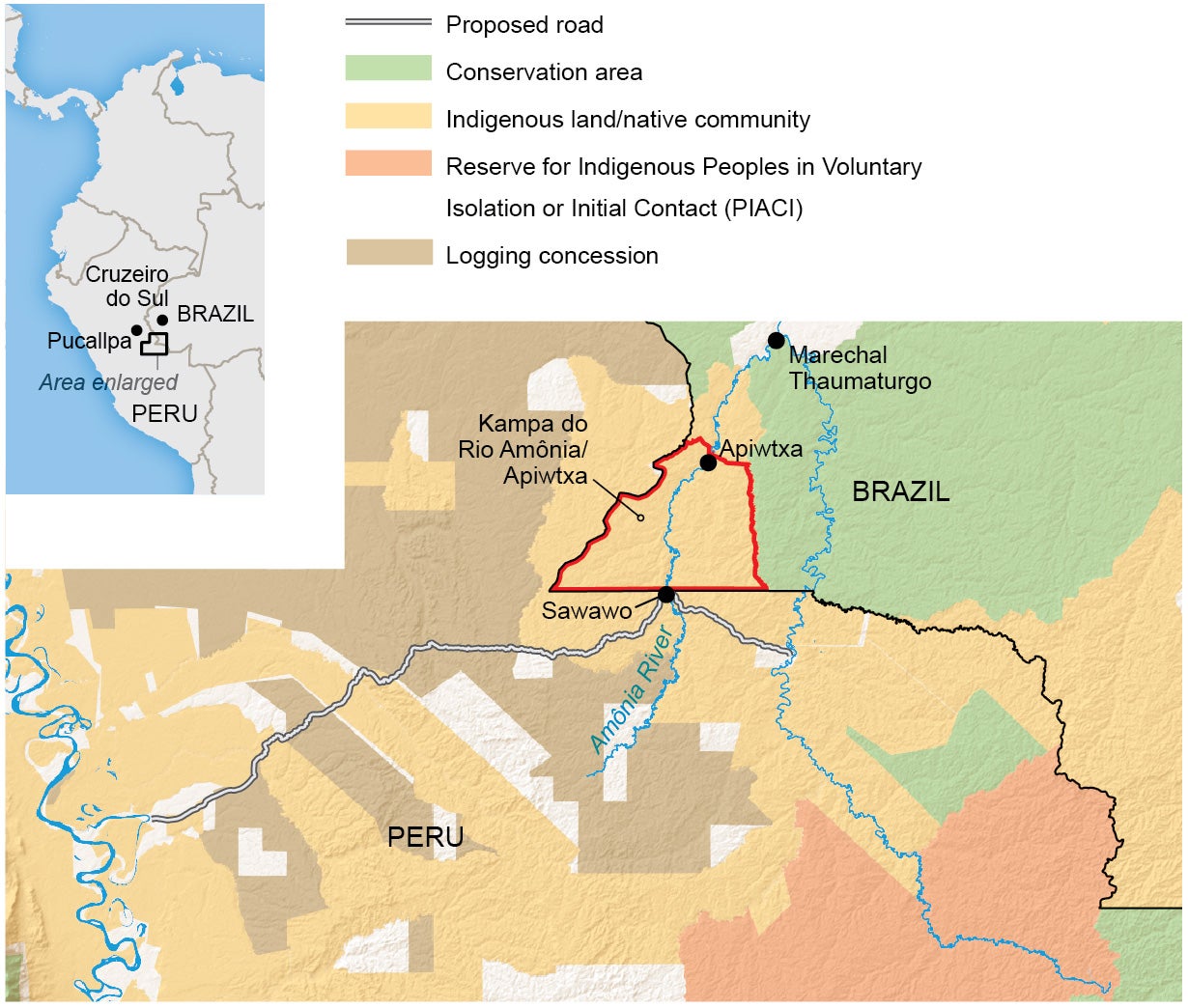

A month later the Ashaninka got the news they had been anticipating, that a road-building project was moving forward. Logging companies moved heavy equipment from mainland Peru to a village at the edge of the Amazon forest to cut an illegal road. Loggers would use the waterway to penetrate the rain forest and cut down trees once the road reached the river. The birds and animals were scared away by the noise of chain saws. Both violent encounters with newcomers as well as casual interactions would spread germs to forest peoples who have little immunity. Drug traffickers would clear the forest and establish coca plantations to sell drugs. The road would bring destruction.

The Amazon rain forest slopes gently toward the Andes foothills, which is rich with biological and cultural diversity. It is also home to the woolly monkey and several Indigenous groups. Two national parks, two reserves for Indigenous people in voluntary isolation, and more than 26 Indigenous territories are protected. The nearest large town, Pucallpa in Peru, is more than 200 kilometers away over dense forest, while the tiny town of Marechal Thaumaturgo in Brazil can be accessed by charter.

The region has been threatened by colonizers for hundreds of years. The Ashaninka joined Indigenous alliances to fight off invaders or flee into deeper forests to escape them. In the 1980s, technological advances made it easier for outsiders to cut through the jungle for logging, ranching, industrial agriculture and drug production.

The Apiwtxa Ashaninka responded to the intensified assaults with increasingly sophisticated andmultidimensional resistance tactics, which included seeking allies from both Indigenous and mainstream society. They came up with a strategy for the long-term survival of the community. The Apiwtxa designed and achieved a sustainable, enjoyable and largely self-sufficient way of life, maintained and protected by cultural empowerment, Indigenous spirituality and resistance to invasions from the outside world. We have the right to look after this land and prevent it from being destroyed by people who don't belong here.

The Sawawo people were first in the line of invasion and had been working with the Apiwtxa to resist the loggers. When the loggers arrived, members of Sawawo's vigilance committee traveled in their boats. Two and a half hours later, they came upon two tractor. Laden with people, food, fuel and equipment, the vehicles had crossed the river into Ashaninka territory. The defenders took pictures of the destruction and went back to their village with internet access. They reported the intrusion to the authorities and asked for an environment official to survey the damage. They shared the evidence with the allies and set up a camp waiting for reinforcements.

Supporters from three regional NGOs arrived on foot nine days later. They saw two more tractor arrive with supplies. More than 20 people, led by a woman carrying her baby, put themselves in front of the tractor to prevent the loggers from crossing the AmF4;nia. The Ashaninka, who have a reputation of being fierce warriors, immediately took the keys from the stunned drivers.

The official arrived the next day. The Ashaninka handed over the tractor keys after he scanned the environmental damage. The people of Sawawo kept a presence in the camp for months to make sure that the tractors were not used for a new assault on the region.

The logging companies left the area. They were temporarily unnerved by the Indigenous resistance and the pressure from the global media. In November of 2021, when a gathering of local Indigenous groups was taking place in Apiwtxa village, the Peruvian government authorized the retrieval of the tractor. One of the companies is trying to get individual Indigenous leaders to sign logging contracts with them, using a tried-and-true tactic. The Ashaninka have been fighting for decades.

The Ashaninka people obtained legal title to some 870 square kilometers of partially degraded forest along the Am F4nia River in 1992. The residents of the village of Apiwtxa in the Indigenous Land of Brazil have become self-sufficient since European missionaries and colonizers arrived in their homeland three centuries ago. They hope that hunting, gathering, and shifting cultivation will ensure the continuation of their community and principles, and that they have regenerated the forest, which had been damaged by logging and cattle ranching. The United Nation's Equator Prize was one of the awards they earned.

The protection and nurturing of all life in their territory is predicated on the designs for living drawn from shamanic visions and interactions with the non-Indigenous world. The Ashaninka hold that their well-being depends on how the Amazon is maintained. Their intimate relationships with the plants, animals, and other elements of their landscape, which they regard as their close relatives, are the main source of this awareness. The Ashaninka call the plant ayahuasca (Banisteriopsis caapi), which they say helps treat their diseases and guide their decisions through visions.

As architects of their future rather than passive victims of circumstance, the Apiwtxa are living a concept outlined by development scholar. Social design is a means by which traditional and Indigenous peoples create innovative solutions to contemporary challenges. When the mode of being in the world is interrupted, it is important for new ways of living to emerge. Securing a territory is important for the design to flourish. The community has fought against social and ecological disintegration to take control of its own fate and that of the creatures they live with and depend on.

I first came to the village in 2015 to do research for a PhD. It took four sets of clearances to get there, from my university, two Brazilian agencies and the Apiwtxa. It was not easy to study the Ashaninka. The history of dispossession and exploitation of non-Indigenous people has made them wary of outsiders. It took some months for them to allow me to stay. My willingness to collaborate with their projects, my empathy with their principles, and my deep respect for their courage and wisdom all influenced their decision. I worked with the Ashaninka for two and a half years. It was a great experience.

I had worked with various Indigenous groups since the early 2000s, as a researcher, consultant on the environmental impact of development projects, and later as an employee with the National Foundation for Indigenous Affairs. I was aware of the destruction that the Global North wreaked on forest peoples. The Ashaninka was remarkable for their penetrating analysis of the assaults they faced and their farsighted responses to them. They did not seek a state of development modeled on a Western ideal of progress and growth that many aspire to but only a few can achieve. They were able to find their own solutions to present-day problems. The most difficult thing to become a contemporary is knowing how to become a contemporary.

The Ashaninka have been massacred by loggers, rubber dealers, and colonizers. We were taken as a workforce to serve patrons who told us to cut down the forest and hunt the animals for them so they could live well, and we were massacred by the missions who told us that we knew nothing.

Benki says that his grandfather, Samuel Piy, was the first student to understand the economic imperatives that drove outsiders to exploit nature and Indigenous peoples. He was a shaman who worked on cotton plantations in conditions of debt peonage, a system in which Indigenous peoples were forced to work for a pittance, purchasing their necessities from their oppressors at extortionate prices, rendering them permanently indebted. Samuel escaped the plantations and trekked down the slopes to the rain forest in Brazil in the 1930s. The colonizers were entering the forest via the great rivers.

Benki said that Samuel thought that he did not have a place to escape. I will look with my spirit to see how I can remain connected to other people and beings. The descendants of Samuel say he used his powers to envision the transformation of his people.

Samuel was seen as a pinkatsari, or leader, whose presence made other Ashaninka families move to the area. When one of his sons wanted to marry a non-Indigenous woman from a family of rubber tappers and cattle ranchers, Samuel agreed that she would become an ally. He was correct. Francisca Oliveira da Silva came to live with her in-laws because her family initially opposed the marriage.

Many of the Ashaninka began working for logging bosses in the 1960s who used their lack of knowledge about the outside world to exploit them. Piti explained the relative values of goods to traders, helping them understand how they were being cheated in every transaction. The community founded a collective controlled trading enterprise in the 1980s to break the cycle of exploitation and instead trade on their own terms.

The Ashaninka had never seen such destruction before when industrial logging arrived in the region. It used to take days to fell a single tree with an axe, but now it takes minutes. The forest fell to chain saws. The game animals fled. The Ashaninka celebrations were invaded by workers from distant towns. Brazil adopted a progressive new constitution in 1988 after similar assaults across the Amazon basin. The rights of Indigenous peoples to use the natural resources of their territories in traditional ways were recognized. With the new constitution in place, the Ashaninka sought the help of FUNai.

They were besieged by death threats. braving ambushes is what it took to ferry the necessary documents between Cruzeiro do Sul and Apiwtxa. Piti and his family pressed Brazilian authorities for the right to control how resources are used in their area. Many Ashaninka families left out of fear after the land title came through. Their sense of security was increased by the fact that Samuel died in old age.

The Ashaninka families, led by Piti and others, realized that unity and cooperation were key to survival and embarked on a process of collective planning to determine their future. What kind of life would they like to have? Benki said that they surveyed their territory and their experiences so that they could reflect on the changes they had to make. It would take three years of exploration and discussion to develop a management plan to ensure adequate, enduring resources.

Roughly 200 people formed the Association to represent their interests to civil society and the Brazilian state. They decided to move the community to the northernmost part of their territory because it was a good location to fending off invaders and to maintain their social integrity and governance system. The Ashaninka built a small village that would be easier to protect, and they named it Apiwtxa.

One of the key governance principles of the community is the placing of collective interests above individual ones. If that is what it takes for everyone to agree before embarking on a course of action, the villagers consistently apply it in their struggles. The meetings help the Apiwtxa plan future projects and overcome threats from outside their territory.

The new village was built on two former cattle pastures around 40 hectares. The area was reforested with indigenous species. The huts were built in the traditional way, with raised platforms to keep out snakes, and without walls to let in the breeze. They planted trees around their homes. They established banana groves and multicropped fields with corn, manioc and cotton, dug ponds to breed fish and turtles, and set up no-go areas to prevent overhunting. They established a school that taught children in the Ashaninka language for the first four years and gave both traditional skills and mainstream knowledge. A few of the young people went away to attend university and study the outside world before coming back with their skills.

The day is spent bathing in the river, washing clothes, tending crops, fishing, cooking, repairing huts and playing. Everyone is tired by the time it ends. After the villagers eat dinner, the children can enjoy a story time before going to bed. Some of the women spin cotton, while the spiritual leaders sit under the stars to chew coca leaves. There is a lot of communication among the Ashaninka, through subtle shifts in expression and posture. We would wake up early to the sounds of the forest and sleep by 7 or 8 P.M.

The Apiwtxa decided on regulations in the 1990s that have evolved into a complex system of governance. The leaders of the community include people with formal education or experience in building social movements, as well as shamans, warriors and hunters who deal with internal issues. The Apiwtxa have become good at raising funds from governmental and nongovernmental agencies for projects.

Francisco said that the principle of independence from systems of oppression and the freedom to determine how to live in their territory is essential. The Apiwtxa have enhanced their food sovereignty and implemented economic and trading practices that minimally impact the environment because of the need for a large measure of self-sufficiency. All transactions within and without the community are guided by the ancient ayõpare system of exchange, which goes beyond material exchanges to the creation and nurturing of relationships of mutual support and respect. It happened to me when I lived there, someone might ask me for batteries, and a few days or months later I would find a bunch of fruit on my doorstep.

One example of this system is the Ayõpare Cooperative, which trades only products that do not deplete nature and only with outsiders who support the objectives of the company. The cooperative allows the Apiwtxa to communicate its principles by selling native seeds for reforesting other parts of the Amazon.

Reducing physical threats from the outside world enhances autonomy. The Apiwtxa have tried to create a buffer zone around their territory to help neighboring Indigenous communities bolster their traditions and protect biodiversity. Several Ashaninka groups, especially those in Peru, have adopted unsustainable modes of living due to the long-term subjugation by mainstream society. The shamans believe that changing this state of affairs requires restoring ancestral ways of interacting with nature. Benki said that ancestral knowledge is a vital resource for all of humankind.

The Ashaninka do not agree with the idea that humankind is separate from nature. According to their creation myth, the original creatures were all human, but their creator turned many of them into birds, animals, plants, rocks, and other objects. These beings are related to the Ashaninka, despite being different in form. Many Indigenous traditions hold that plants, trees, animals, birds, mountains, waterfalls, and rivers can speak, feel, and think, and are tied to other beings.

The Ashaninka say that they were taught about the intimate connections among beings. The ayahuasca vine was found in the place where a wise ancestral woman was buried. The Ashaninka was told how to brew the sacred drink from the ayahuasca vine and a particular leaf.

Kamarpi rituals take place at night under a clear sky. The occasion is solemn and there is no fire. The shaman leads the ceremony chants to the spirits in the sky when the psychoactive brew starts to take effect. The others start to sing, too, creating a rapturous polyphony. There are visions at this point. The shaman watches what participants are feeling and intervenes when necessary.

I felt my body dissolving into the surroundings, my self merging with the environment in a way that defies words, giving me a deep sense of theterconnectedness between other beings and me. The kamarãpi ceremony establishes strong bonds among everyone present and between the forest creatures, allowing communication to happen in silence even after the ritual is over.

The kamarãpi helps people develop their conscience by leading them toward self-knowledge and gradually to a deep knowledge of other people and other kinds of beings. This wisdom will help guide their actions. Claude Lévi-Strauss noted that shamans help people gain insight into themselves and their relationships with others. Psychotropic substances can help trauma patients come to terms with their suffering and thus heal. The kamarãpi ritual goes further, creating deep empathy for other creatures, as well as for rivers and other features of the landscape. All come to be seen as connected, an awareness that has profound implications for how people treat nature.

The shamans attribute their capacity to design their society to visions. The shamans seek guidance from ayahuasca in order to attain, sustain and explore an altered state of consciousness that allows them to envision the future and find solutions to challenges. Dreams enable disparate concepts to link up in ways that are not normally available to the rational mind. The shamans in Ashaninka and other Indigenous cultures aim to attain such states of foresight as a means of seeking and wisdom.

Benki says that dreaming is essential but not enough. It is important to plan and act in the present. The community develops a plan of action after a shaman reports a vision. After Benki dreamed about a center for disseminating forest peoples philosophy, the Apiwtxa acted on it.

They built the building on a cattle pasture across the river from a small town downstream. The creators intended Yorenka Atame to be a demonstration of an alternative way of living and turned the pasture into a forest full of fruit trees. Benki had sought to lead its youth away from drug traffickers by training them in forest and inviting them to kamar. The impact of ayahuasca depends on the brew and the skill and ethics of the person supervising it. Benki wanted the ritual to help the young people feel connected to nature. They helped him establish a settlement called Raio do Sol, where they grow their own food, after helping him plant around Yorenka Atame.

There is a place for exchanging knowledge about the forest and discussing what true development might mean. It has hosted many gatherings of Indigenous peoples and scholars from around the world. The Puyanawa peoples, who had been enslaved and almost killed off by rubber barons, have been helped by exchanges at Yorenka Atame and in the field.

The Apiwtxa community has a large presence in the region despite its small size. The first Indigenous mayor of Marechal Thaumaturgo was the son of Piti. He is one of the leaders of the Apiwtxa, a community whose achievements are widely respected.

Benki and others established a project called Yorenka Tasori with its own center. It helps to spread Indigenous spiritual and Medicial knowledge among forest peoples and beyond. Ashaninka sacred sites, which are often places of great natural beauty but are threatened by roads, dams and industries, are also included in Yorenka Tasori. As much as a political endeavor, Yorenka Tasori wants to reestablish traditional links among the Ashaninka as a way of restoring their historically powerful cohesiveness. The Apiwtxa hope to ensure the continuity of the Ashaninka as a people by protecting their ancestral knowledge, awareness of interconnectedness with all other beings, and passing these gifts on to younger generations.

I was struck by how many people were drawn to the Ashaninka sacred sites I visited. Our group grew inexorably as we traveled because they had an aura of power that attracted many others. The chief of one Indigenous community said that it must have been Pawa who sent them to open their eyes, because the leaders of the Apiwtxa inspired hope wherever they went.

The Apiwtxa hope to reach out to us with their message of unity and interrelatedness. They believe that a spiritual awareness of the underlying unity of creatures shows a way out of our era, marked by ecological and societal crises. The geologic era derives from the relentless expansion of humankind's destructive activities on Earth, impacting the atmosphere, oceans and wildlife to the point that they threaten the integrity of the biosphere. The people who live in the land in traditional ways are suffering the most damage from the Anthropocene.

A social and economic system in which collaboration ranks above competition and where every being has a place and is important to the whole is proposed by the Apiwtxa. They are pointing to a pathway out of the Anthropocene by looking after human and other-than-human beings.

Benki made an appeal to the world in 2017: "This message comes from Earth, as a request for humanity to understand that we are Transient beings here and one cannot just look at one's own well-being." We have to think about our children. We can't leave the land impoverished and poisoned. Disasters are beginning to happen as people emigrate out of their countries in search of water and food. There is a war going on for wealth and soon there will be a war for water and food.

Shall we wait or change history? Join us!