The dating application, Facebook Dating, was announced in May. There was a lot of excitement with people expecting a new dating app.

When you consider the size of the company, its technical capabilities, and most importantly the large amount of data that Facebook has collected about its users, it is no wonder. Research shows that Facebook knows us better than our mothers, so why wouldn't it live up to its goal of creating meaningful relationships?

Most people have forgotten about it four years later. Reports claim the dating app doesn't function. About 300,000 people in New York use the service, compared to 3 million in New York.

I was interested in Facebook Dating since its announcement. It took me a long time to look into its market success. I think I know why the app failed.

I was overwhelmed by the number of very attractive profiles that I was exposed to in the first few hours after I activated my Facebook Dating profile. I started pressing and soon received notifications that people liked me.

It is rare for a male heterosexual user to receive a positive signal on a dating app. My phone kept buzzing for hours. I realized this was too good to be true with the matches seemingly out of my league.

I started talking to see what was happening. I made it clear on my profile that I was there just for chatting, because I didn't have ethics clearance from my university.

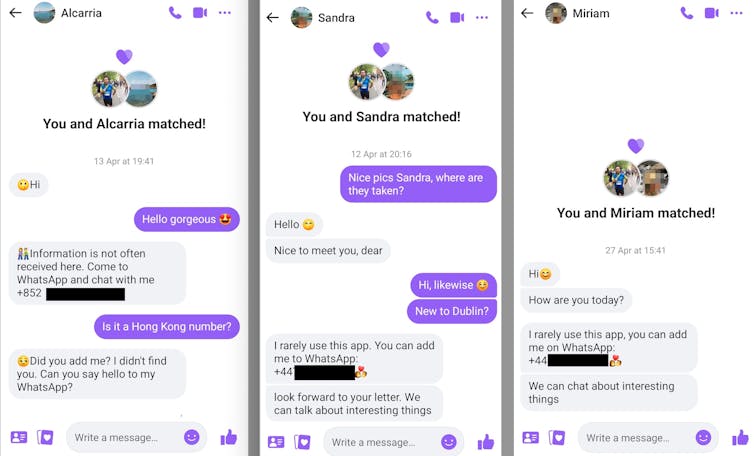

I got a phone number and an invitation to use the messaging service, but I didn't use it. This usually happens after at least 20 messages and within a few days. According to science, this was light-speed-dating.

Within a few hours, I had a long list of attractive matches who all wanted to talk to me. Even though they all lived in Ireland, nobody sent me an Irish number.

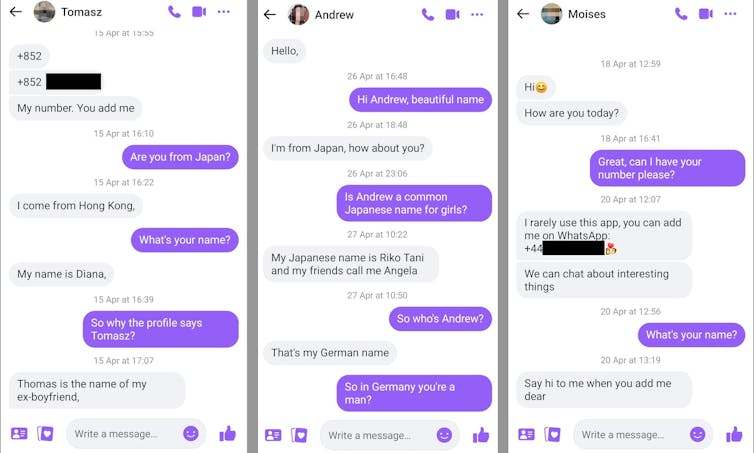

Things got even weirder quickly. As I continued liking and matching on the app, I began to see Tomasz, Moises, and Andrew as my profile names, as they looked very similar to the text messages. She said that her German name is common for girls in Japan. Diana said it was her ex-boyfriend's name and Moises didn't reply.

At this point, I suspected that I was dealing with an organized scam with the goal of getting my phone number via a chat with my name, and heaven knows what will happen next.

If there is a company that could verify the authenticity of its users, it would be Facebook. The wealth of data that we have shared with the app makes it easy for them to verify accounts. We use the Facebook system to log in to other services and apps.

Why didn't Facebook remove all the fake profiles?

There were a lot of scandals, including the Cambridge Analytica one. The use of personal data for matching purposes might have raised more angry voices. The original vision for Facebook Dating may have been dead before it was launched.

The primitive design of the app suggests that there was little attempt to compete with the existing dating apps. Ten years ago, you had a similar experience on a dating app.

Meta allows fake accounts to be used around Facebook Dating. There aren't many real users. If the fake accounts are removed, the app will become empty and Facebook wants us to stay longer.

What can we learn from this? It is important not to share your phone number or other private information before a level of trust is built, as it might be hard for users to detect fake accounts immediately. Generic profile descriptions, inconsistent replies to your messages, andager invitations to take things to the next level are all bad signs.

The number of Facebook users grew for the first time in a decade this past quarter. This may be the reason why the company decided to change its name to separate Meta from Facebook, and focus on other areas, such as the metaverse. The failure of Facebook Dating may be an early sign that the problems with Facebook are deeper than previously thought.

The Conversation tried to get a reply from Meta.

The Conversation has a Creative Commons license for this article by Taha Yasseri, Associate Professor, School of Sociology, University College Dublin. The original article is worth a read.