In July of 2003 the physicist and Pulitzer-prize-nominated author Dr Tony Rothman received an email from his editor. The new book was weeks away. The title, Everything's Relative, was a nod to Albert Einstein's theory of relativity. A picture of history's most famous scientist was put on the cover.

An issue just came up in the email. Einstein's estate is extremely aggressive and litigious, according to the editor. The editor explained that the publisher could be sued if they didn't pay a hefty fee to use the image of Einstein. The estate would have no time if they went after everyone who used Einstein's image. Are you sure that they own it? He referred to the heirs as the slavering jackals, who run the literary estate of an American writer.

Albert Einstein died in 1955. He promised in his last will and testament that his literary property would be left to his secretary, Helen Dukas. Einstein did not mention his name or likeness in his will. At the time Einstein was writing his will, there was no legal concept for publicity rights. When the Hebrew University took control of Einstein's estate in 1982, publicity rights were worth millions of dollars a year.

The university began to control who could use Einstein's name and likeness in the 1980's. Potential licensors were told to submit proposals, which would be assessed by an unnamed arbitrator. An Einstein diaper? No. An Einstein calculator? Yes. The university could take legal action against anyone who did not follow the process. The sellers of Einstein-themed T-shirts, Halloween costumes, coffee beans, SUV trucks and cosmetics were in court. Coca-Cola, Apple and the Walt Disney Company were all targets of the university.

Einstein was a well-paid man. His salary was set by the university to exceed that of any American scientist. His earnings in life were insignificant compared to his earnings in death. He was on the Forbes list of the 10 highest-earning historic figures every year for the past decade. Einstein's postmortem earnings for the university have been put at $250m by a conservative estimate.

Critics are unconvinced that Einstein would have wanted the university to take on alleged infringers. He resisted attempts to commercialise his identity. Why would he change his position in death? The institution and others like it were described as the new grave robbers by an American law professor in the New York Times. A lawyer for Time Inc called the agents acting for the university a group of tribal headhunters. The manufacturer of a children's novelty Einstein costume is among the scores of businesses that have protested against the university. It isn't interested in discussing the matter beyond this. The university agreed to reply to email questions after rejecting my request for an interview. Its responses were brief. It answered most of the factual questions. It stated that it is entitled to enforce its legal rights and did not want to give any further details.

The matter is not settled. The law around postmortem publicity rights is a complete mess. Brazil, Canada, France, Germany and Mexico have national laws that specify the definition and duration of postmortem publicity rights, but the law in the US is different. Only 24 states have adopted a formal statute on postmortem publicity rights, which can last anywhere from 20 years after a person's death to 100. A celebrity who dies in California has more rights than a celebrity who dies in New York. New Jersey, where Einstein died, is one of 17 US states that does not limit the heir's right to profit from a dead celebrity.

The Hebrew University continues to profit from Einstein's name and likeness, even though lawyers debate obscurities of law. The British government paid an undisclosed sum to use Einstein to front a nationwide TV and online advertising campaign for smart energy meters. The university is currently in a case in Illinois where a statute protects everything from a celebrity's likeness to their mannerisms for 100 dollars.

The publisher claimed that the university had the power to ban Einstein from the cover of his book. How could an institution dedicated to learning claim ownership of a public figure's image? His publisher was unwilling to take on a costly legal battle. The mock-up was of the cover. Thomas Edison replaced Einstein.

The design sucks and I demand that you go back to the original. They were deterred by the university's reputation. The cover of Everything's Relative showed a cloud that spelled out the world's most famous formula. The author was nowhere to be found.

The power of images was understood by E instein. He conjured simple scenes to show complex ideas, such as a train speeding through a lightning storm and a blind beetle. He would joke that a minute sitting on a hot stove seems like an hour, but an hour sitting with a pretty girl passes like a minute.

Einstein did not have promise as a baby. His maternal grandmother exclaimed that he was too fat when he saw his head for the first time. The family maid said the boy was too fat. Einstein's parents made an appointment with the doctor to find out if there was something wrong with him because Einstein took so long to learn to talk. The schoolmaster said that the most distracted student would never amount to anything.

Einstein was rejected for several junior academic jobs after graduating from the Polytechnic. While working at the Bern patent office, he developed scientific theories and began to publish them in 1905. Einstein's ideas were grasped by other scientists and in 1909 he became professor of theoretical physics. Einstein became world famous in 1919.

During a solar eclipse, the English astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington conducted a photographic experiment to evaluate one of Einstein's theories: that gravity bends light over distance. The position of the planets, stars and moon would have to be adjusted. In Britain, scientists took pleasure in ignoring or denigrating their German counterparts. The great and the good came to the Royal Society of London in 1919 to hear the results of Eddington's experiments. The Times delivered the news to the world the next morning. There is a new theory of the universe. The New York Times declared Einstein's discovery the greatest achievement in the history of human thought. The world was knocked off its axis by the drug.

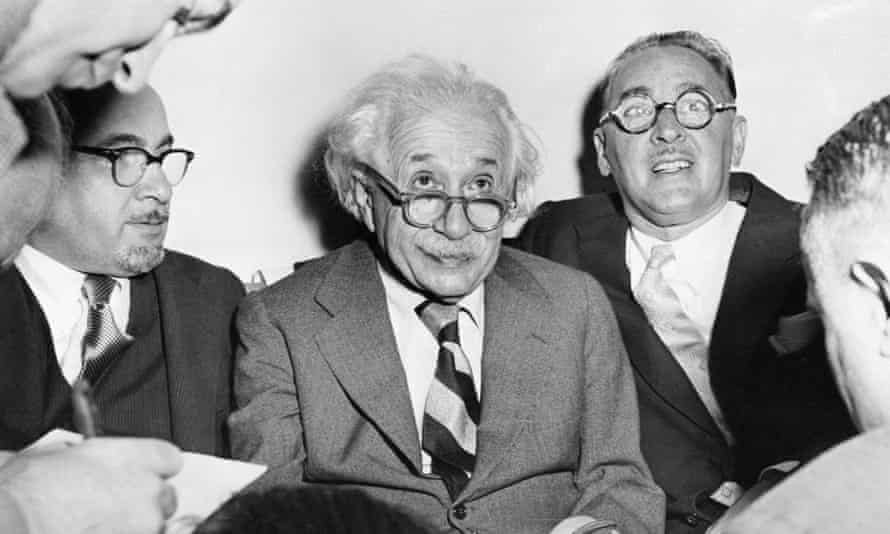

Einstein was reborn as a public figure in this, the first flowering of mass media. Good copy was made of Einstein's easy wit and talent for aphorism. He wrote editorials for national newspapers. Einstein had a charisma that caused a kind of mass hysteria.

It was his appearance that made Einstein an icon. The New York Times wrote that Einstein's image was easy to understand because of the way it was spread through print and television. Robert Schulmann, a former editor of the Collected Papers of Einstein, told me that he was slovenly.

Einstein's work as a humanitarian, philosopher, pacifist and anti-racist continued throughout his life. Einstein never returned to his homeland after Hitler came to power. The Hitler Youth used his summer house in Caputh. After his theories helped build the atomic bomb, he became a vociferous pacifist and worked to help refugees escape Nazi oppression. Einstein's fingerprints can be found on many of the technologies that make the modern world work, from lasers to the semi-conductors that power your phone. It is Einstein's image that has been the most enduring in the public eye.

Einstein was in New Jersey to celebrate his 72nd birthday when he saw a camera held by American photographer Arthur Sasse. Einstein poked his tongue out as he looked down the lens. The image was sent to the editors by Sasse and they debated whether to publish it. The picture provided the most famous and enduring image of the scientist: a loveable joker who also happened to be an era-defining genius. Nine copies were ordered by Einstein.

Einstein died at the age of 76 on April 18, 1955. He left instructions for Otto Nathan, his trusted friend and the executor of his estate, to prevent posthumous idolatry. Einstein wanted his ashes to be scattered over the Delaware river on the Atlantic coast. His work would be his legacy. The brain of Einstein was taken from the hospital where he died. Harvey wanted to study the most impressive organ that had been produced. Harvey picked the wrong relic for future dividends. The world wanted Einstein's brain, but it was his face.

Roger Richman saw a picture of Albert Einstein in the living room of his parents' house. Einstein befriended Richman's father, Paul, in the 1930s, when they worked together to help German Jews resettle in Alaska, Paraguay and Mexico. Most of the US was closed to those fleeing Nazi oppression. The Richman family was close to the keepers of Einstein's legacy after Richman's father died in 1955.

In 1978 Richman founded an agency that specialized in product placement in film and TV. The heirs of a late American comedian contacted his office. They wanted Richman to be his agent because Fields had been dead for 32 years. The heirs of Fields hoped that Richman could ban the sale of the poster that showed the comedian's head superimposed on a body. The celebrity's publicity rights did not extend to heirs.

While researching the law, Richman found a case involving the son of a famous actor. In 1966, the son of Lugosi sued Universal Pictures, claiming that he and his stepmother owned his father's image rights. The high court overturned the ruling because the father had not sold his image for commercial purposes during his lifetime. The heirs of any celebrity who sold his or her image during their lifetime had a claim on their publicity rights, according to Richman.

The US Postal Service planned to issue a stamp in honor of the 100th birthday of WC Fields, which gave Richman an opportunity to test his theory. He mentioned the judgement of the high court in the case. The first licence fee was paid to the estate of a dead celebrity.

Marilyn Monroe and Sigmund Freud were some of the dead clients built by Richman. Richman offered the descendants of late celebrities a way to protect their loved ones from legacy-tainting associations and to make some money along the way. Advertisers were eager to work with the dead who, unlike the living, did not become involved in new scandals, fail to turn up for expensive photo shoots, or demand costly contract renegotiations. The recipients of Richman's legal letters were skeptical. Will Clark, the co-owner of Baby Einstein, told me that companies used to abide by established libel, copyright and trademark law were nowambushed by questionable legal claims. He was pushing a boulder up the hill.

Richman believed he was the only one who could fight the major advertising agencies, broadcasters, film studios, manufacturers and publishers. How could anyone not want to sell a presidential dildo?

Richman should draft a celebrity rights law to add legal heft to his threats. Richman thought the idea was crazy. Richman wrote more than 80 letters to the widows and orphans of celebrity greats and amassed a group of powerful supporters, including Elizabeth Taylor. The California Celebrity Rights Act passed after two rejections. In California, heirs can now inherit the publicity rights of their celebrity ancestors who have died in the state. Richman was in business because of a legal precedent in California. He decided to come to the aid of his father's friend, Albert Einstein.

Einstein fought any attempts to use his name and likeness as a promotional stunt. The proposal that it be renamed Einstein University was barred by him. Nobody seemed to care what Einstein wanted. By the 1980s Einstein's likeness was attached to everything from frisbees to snow globes, lending them a frisson of intellectual glamour. Almost every company in the world was willing and able to profit from Einstein.

Richman started collecting clippings of advertisements that featured Einstein after the Celebrity Rights Act was passed. He sent a folder of material, including ads for cars and hair salons, to Einstein's executor, Otto Nathan, with a letter asking whom he should contact, as he put it. The clippings were forwarded to the Hebrew University. Richman was appointed Einstein's exclusive worldwide agent by the university in July of 1985 after seeing an opportunity to exert some influence over the use of Einstein's likeness. The Hebrew University's designated gorgon-watchdog was described by the newspaper US1 as Richman.

Richman was in favor of the deal with the Hebrew University. He took a cut from every licence deal, or at least half of it, for successful legal actions against infringers. Richman considered his work a moral campaign to protect the legacy of the 20th century's defining icon. Einstein would not be associated with tobacco, alcohol or gambling according to the guidelines drawn up by Richman. There was no fabrication of formulas or quotations. Advertisers couldn't draw a thought bubble on to a picture of Einstein and try to fill his mind with their words or ideas. He claimed his personal connection to Einstein made him stronger in his resolve to only allow affiliations.

The American Friends of the Hebrew University in New York were given the responsibility for dealing with the flood of requests to a volunteer, Ehud Benamy, because Richman was a relentless Einsteinseeker. Richman sent every proposal to Benamy. Benamy and Richman agreed that the famous photograph of Einstein sticking out his tongue was in bad taste. The Hebrew University conceded that it should not veto Einstein's pose. Richman believed that an association with an Italian manufacturer of ovens may upset Jewish holocaust survivors.

Computer manufacturers wanted to associate their products with Einstein. Sony paid $63,000 to use Einstein's image in an advertisement. Richman was told in 1997 that Apple wanted to use Einstein's photograph to promote its Macintosh computers. After Richman had negotiated a fee of $600,000, Steve Jobs called and demanded a reduction. He said that Jobs could license Mae West if the fee was too high.

Despite Richman's best efforts, some products reached the market. When Richman discovered that a chain of stores owned by Universal City Studios sold a sweatshirt with a slogan, he successfully had the sweatshirt banned, and forced Universal to pay $25,000 in damages. The video game series Command and Conquer, launched in 1995 by Electronic Arts, allowed players to click a few keys and kill Albert Einstein. Richman wanted a sticker on the box to warn of antisemitic content. The right of posthumous publicity was replaced by the right of fictional writing about historical characters. The parties agreed to leave the court.

Richman disliked the fact that he was portrayed in court and the press as a marketing ghoul. He wrote that it was a bad portrayal since he had written laws preventing snakes from entering people's lives. Richman was portrayed as an opportunist money-grabber as a Jewish businessman. Richman was committed to securing the Hebrew University and himself the most favorable terms. When Richman learned that the Baby Einstein company was in talks to sell, he demanded that the licence fee be increased. Will Clark, the co-owner of Baby Einstein, believes that the university publicised the final licence figure to establish validity of licensing Einstein's name and pay a premium for it.

Richman began to target companies that used Einstein's name without intending to be associated with the physicist. The Einstein Bros Bagel company relented to the demands of the university. Richman's aggressive stance presented a troubling ethical dilemma for one academic at the Hebrew University.

The assistant curator at the Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University in Israel received as many as 30 faxes a month from Richman's office. Each fax contained a proposal from a different company that wanted to use Einstein's name or likeness in its product or service. It was up to the young academic, who was familiar with Einstein's thoughts and values, to bless or veto each offer. I was told recently that the responsibility was overwhelming. The universe decided that this would be my role.

After Ehud Benamy died, the task was taken over by Rosenkranz. The academic had to balance his speculation as to what Einstein wanted with the pressure he felt from Richman to greenlight anything that did not carry an obviously harmful association.

The companies would say that the people were dead. There was a word processor that was popular. The argument worked and the company never paid.

While Richman fought its profitable battles, the university seemed happy to keep a low profile.

He was uneasy about his role. He believed Einstein was against most marketing associations. Richman put pressure on him to approve more proposals. Richman was unhappy when he rejected the deal with Huggies. I'm in academia. It wasn't an easy topic.

Richman persuaded the Hebrew University to file a number of trademarks for Einstein-related products, which he argued would be easier to defend. There were nearly 200 separate items that the university held trademarks for, including metal detectors, umbrellas, arcade games, Christmas tree decorations, butterfly nets, water-squirting toys and life-size cardboard cutouts.

The first time I saw a trademark symbol, it was deeply uncomfortable. The lawyers told me that international trademarks were important to guarantee the rights, and that the university could now use them in countries where there was no posthumous right of publicity.

There were other people who felt uneasy about the arrangement. Evelyn, Einstein's adoptive granddaughter, announced plans to file a lawsuit against the Hebrew University in early 2011. Evelyn told a journalist from the New York Post that she was offended by some of the stuff that was being OKed. Evelyn's friend, the lawyer Allen Wilkinson, told me that Evelyn could not stand the fact that they were making money off of Einstein bobbleheads and other items that have nothing to do with literary rights. Evelyn claimed that the university ignored her requests for an arrangement that would allow her to profit from the sales to help pay her medical bills.

Evelyn had her day in court. After her death, a case was heard in California that seemed to settle the question of Albert Einstein's ownership for good.

The Hebrew University protested after General GM placed an advertisement in People magazine with a picture of Einstein on a muscled body.

The Hebrew University took GM to court in an attempt to prove that Albert Einstein would have transferred his postmortem right of publicity under New Jersey law if he'd known about it. Even if the university could prove Einstein's intent with respect to the right of publicity and GM's violation of that right, enough time had elapsed between Einstein's death in 1955 to nullify the point.

There were problems with the trial. The case was going to be heard in a California federal court, but the presiding judge decided to apply New Jersey state law to the case. New Jersey does not require any duration of publicity rights for 70 years after a person's death. It took seven months for Matz to make a decision.

Hebrew University loses lawsuit over Einstein image. This seemingly conclusive verdict was far from clear cut. The case was sent back to the lower court for further proceedings after the university appealed the decision. What is the law in the state of New Jersey regarding the existence and duration of postmortem publicity rights? We only have the best guess of an out-of-state federal judge.

There have been repeated calls for the US Congress to pass a uniform statute for the entire country. The law outside of the US is the same as it is in the US. There are living heirs in Brazil who have posthumous rights. The period in Germany is 70 years. There is no clear right of publicity in England and Wales. Lawyers who want to protect an individual's image and personality must resort to a patchwork of legal rights.

After Richman's death, the photo agency that he had sold Einstein's publicity rights to was renamed GreenLight Rights. The business of managing Einstein's image has become more sophisticated since then. GreenLight works with companies that use special software to identify counterfeit and copyrighted goods.

A panel of experts at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have the power to bless or veto a licence request. Commercial requests are considered by the panel. The university has agreements with photo libraries that allow media outlets to use photographs of Einstein to illustrate stories. Yishai Fraenkel, vice president and CEO, said that speech bubbles are always turned down because of Richman's original guidelines. It does not seem appropriate or lawful to include the names of individuals on the panel, according to the university.

Einstein's earnings have not slowed since his death six decades ago. Einstein's brilliance and unforgettable appearance are not the only things that make him so in demand. It has always been easy for diverse groups to embrace Einstein as their own. He opposed the creation of a Jewish state and deplored the victimisation of Palestinian Arabs, while raising funds for Zionism, but he believed in God.

What would Einstein think of his presence on the screens, billboards, posters and T-shirts of the 21st century? Would he have been happy with the Hebrew University's stewardship of his legacy? He was seen but not heard in life. The man who spent 12 years trying to determine what Einstein thought about Einstein- branded pencils and Einstein- branded Christmas tree decorations was happy when I spoke to him. I am not sure if he would have been happy.

The question of who owns Albert Einstein remains unresolved even after the death of the man. The New Jersey legislature was working with a colleague in Washington on a posthumous publicity statute. The state legislature will hear testimony from Schechter. The statute was put on hold after the Pandemic struck. The duration of postmortem publicity rights was aligned with that of copyright law. We could be fighting a battle if New Jersey were to resurrect the statute and adopt this generous postmortem right.

The university's reputation continues to have a powerful deterrent effect as Einstein's money continues to roll in. A former curator at one of London's most famous museums told me that he had removed Einstein's image from publicity materials on the advice of a colleague. A spokeswoman for the university warned that the article could interfere with the university's commercial agreements, good name, or that of Dr Albert Einstein. The Einstein panel at the Hebrew University makes the ultimate decision after applications are passed on. The name of the site is straightforward.