The Blood Moon is back! The total lunar eclipse will take place in May 2022.

May 11: Final Hubble Servicing Mission launches.

0:57

The total eclipse of the moon is the most colorful of all astronomy phenomena.

Each lunar eclipse is unique, with its brightness and color determined by a range of factors, such as the geometry of the eclipse and the large-scale meteorological conditions on Earth. Secondary phenomena may be overlooked when the moon is entering and leaving Earth.

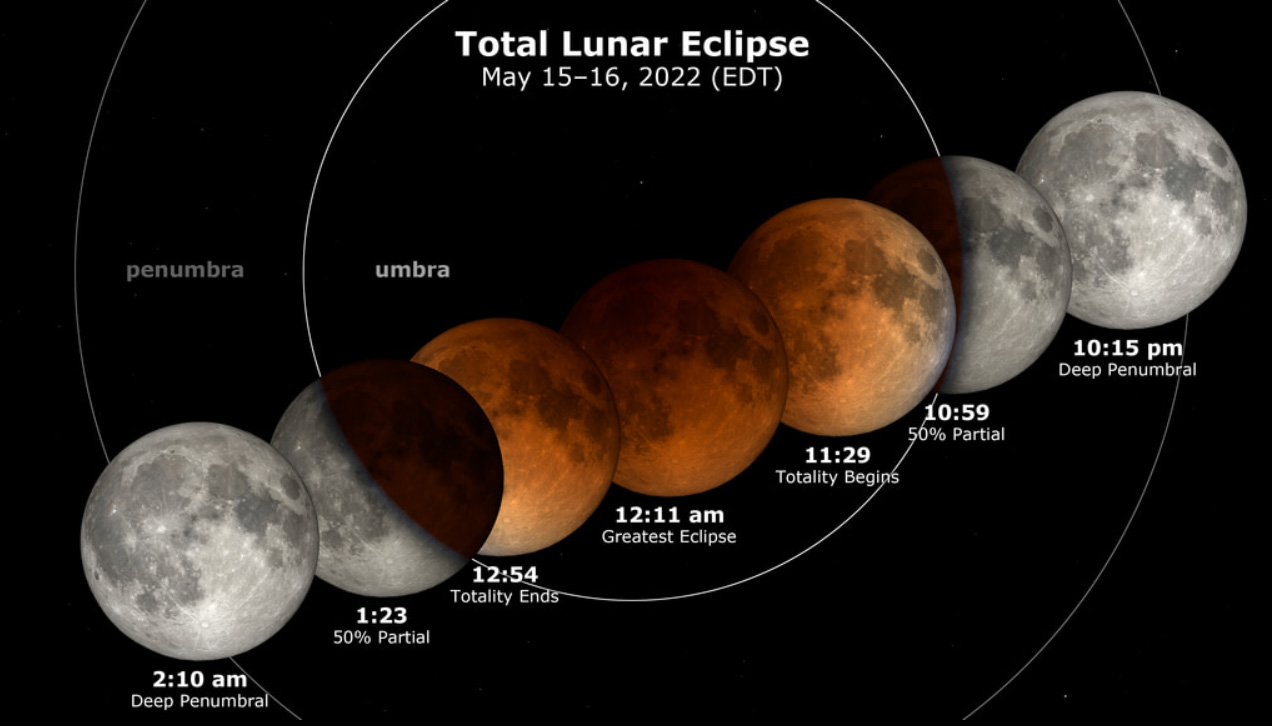

The upcoming total lunar eclipse will take place on May 15-16, and Space.com's Joe Rao has prepared a chronology to help you prepare. No two eclipses are exactly the same.

Observers who know what to look for will have a better chance of seeing the various stages. If the moon is below the horizon in your location, or if bright lights or cloudy skies prevent you from seeing the event, you can watch it on the internet. The Blood Moon total lunar eclipse can be watched online.

The May full moon is known as the Flower Full Moon and is occurring when the moon is near perigee, its closest point to the Earth for the month.

There is a Super Flower Blood Moon lunar eclipse.

| Stage | GMT | ADT | EDT | CDT | MDT | PDT | AKDT | HST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Moon enters penumbra | 01:31 a.m. | 10:31 p.m. | 9:31 p.m. | 8:31 p.m. | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 2) Penumbral shadow appears | 02:10 a.m. | 11:10 p.m. | 10:10 p.m. | 9:10 p.m. | 8:10 p.m. | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 3) Moon enters umbra | 02:28 a.m. | 11:28 p.m. | 10:28 p.m. | 9:28 p.m. | 8:28 p.m. | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 4) 75% coverage | 03:13 a.m. | 12:13 a.m. | 11:13 p.m. | 10:13 p.m. | 9:13 p.m. | 8:13 p.m. | ---- | ---- |

| 5) Five minutes to totality | 03:25 a.m. | 12:25 a.m. | 11:25 p.m. | 10:25 p.m. | 9:25 p.m. | 8:25 p.m. | ---- | ---- |

| 6) Total eclipse begins | 03:29 a.m. | 12:29 a.m. | 11:29 p.m. | 10:29 p.m. | 9:49 p.m. | 8:49 p.m. | ---- | ---- |

| 7) Middle of totality | 04:12 a.m. | 1:12 a.m. | 12:12 a.m. | 11:12 p.m. | 10:12 p.m. | 9:12 p.m. | ---- | ---- |

| 8) Total eclipse ends | 04:54 a.m. | 1:54 a.m. | 12:54 a.m. | 11:54 p.m. | 10:54 p.m. | 9:54 p.m. | ---- | 6:54 p.m. |

| 9) 75% coverage | 05:12 a.m. | 2:12 a.m. | 1:12 a.m. | 12:12 a.m. | 11:12 p.m. | 10:12 p.m. | 9:12 p.m. | 7:12 p.m. |

| 10) Moon leaves umbra | 05:56 a.m. | 2:56 a.m. | 1:56 a.m. | 12:56 a.m. | 11:56 p.m. | 10:56 p.m. | 9:56 p.m. | 7:56 p.m. |

| 11) Penumbral shadow fades | 06:12 a.m. | 3:12 a.m. | 2:12 a.m. | 1:12 a.m. | 12:12 a.m. | 11:12 p.m. | 10:12 p.m. | 8:12 p.m. |

| 12) Moon leaves penumbra | 06:52 a.m. | 3:52 a.m. | 2:52 a.m. | 1:52 a.m. | 12:52 a.m. | 11:52 p.m. | 10:52 p.m. | 8:52 p.m. |

Local circumstances are provided for eight time zones. The moon has not yet risen above the horizon.

There is a breakdown of the stages of the blood moon total lunar eclipse.

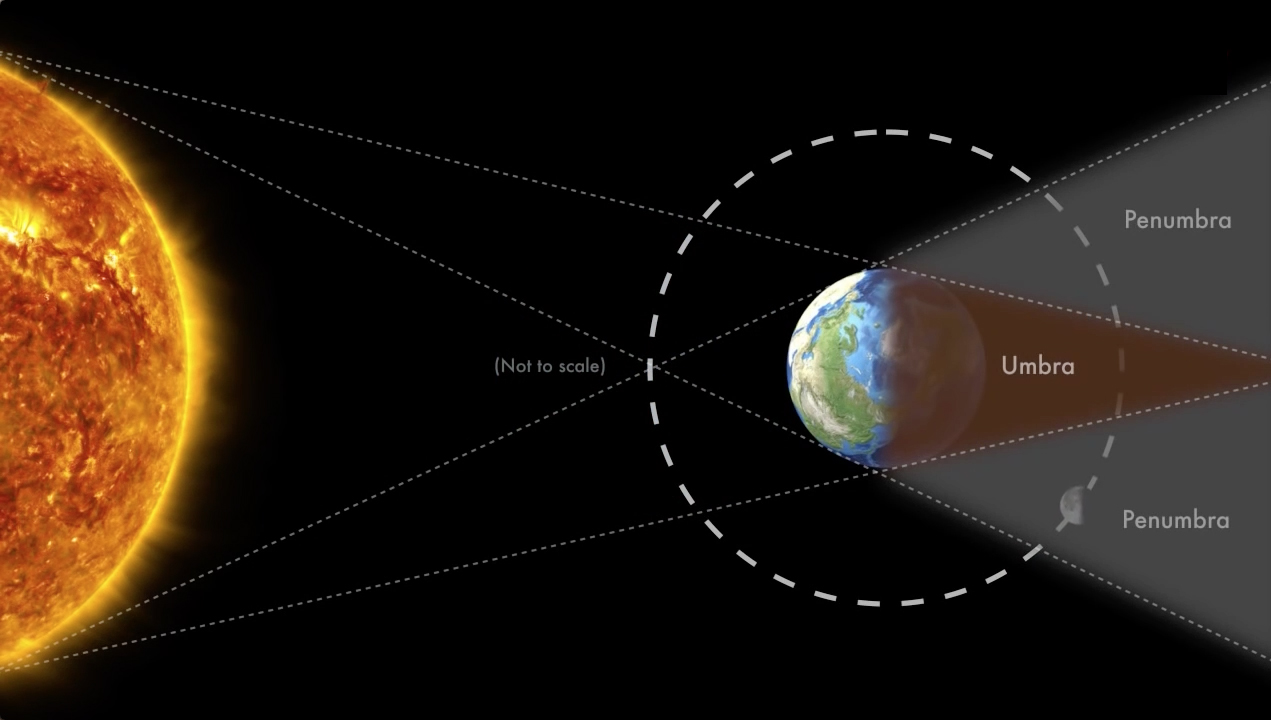

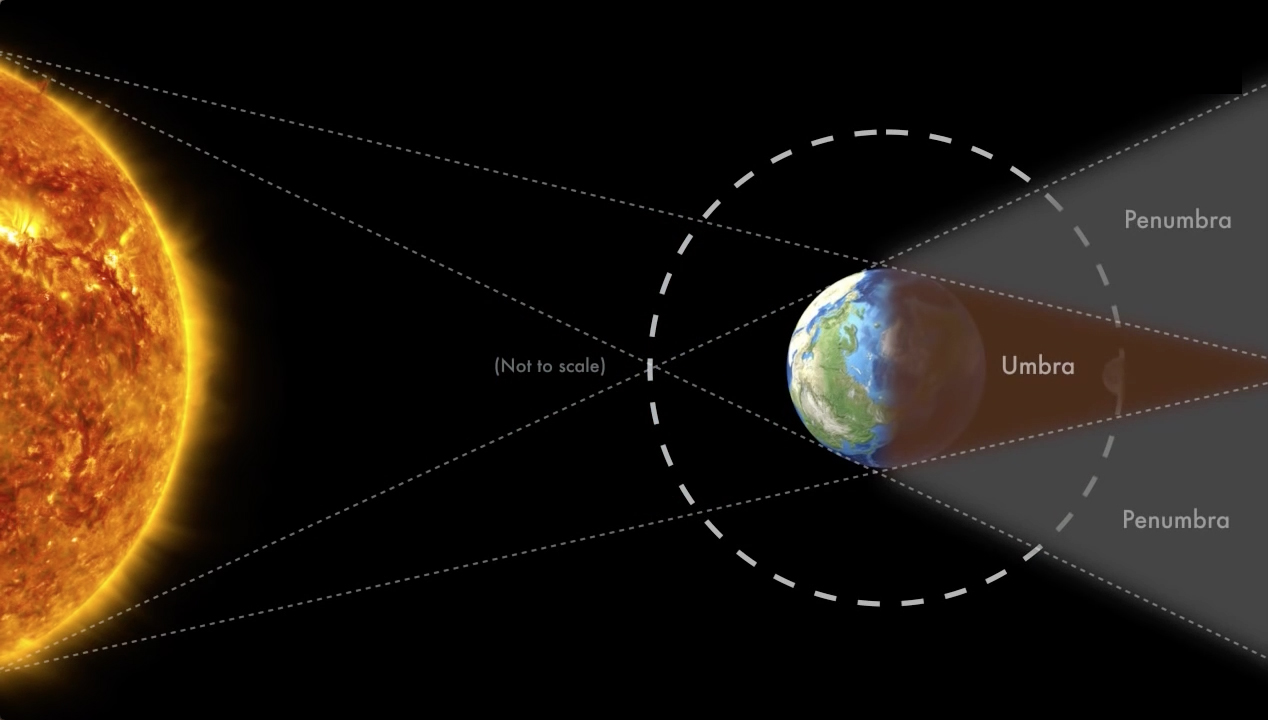

The shadow cone of the Earth has a dark inner umbra and a lighter penumbra. The penumbra is the outer part of the shadow. You won't see anything unusual happening to the moon until the eclipse is over. When the penumbra has reached 70% across the moon's disk, the Earth's penumbral shadow becomes invisible. For about the next 40 minutes, the full moon will appear to shine normally, but with each passing minute, it is progressing deeper into Earth's outer shadow.

The moon should be visible on the moon's disk now that it has progressed into the penumbra. Start looking for light shading to appear on the left portion of the moon. As the minutes pass, the shading will spread and deepen. The penumbra should appear as a smudge or tarnishing of the moon's left portion just before the moon enters Earth's dark umbral shadow.

There is a Super Flower Blood Moon Eclipse.

Let us know if you take a photo of the eclipse. You can send pictures and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

The moon now begins to cross into Earth's dark central shadow, called the umbra. A small, dark scallop begins to appear on the moon's lower-left (southeastern) limb. The partial phases of the eclipse begin; the pace quickens, and the change is dramatic. The umbra is much darker than the penumbra and fairly sharp-edged. As the minutes pass, the dark shadow appears to slowly creep across the moon's face. At first, the moon's limb may seem to vanish completely inside the umbra. But much later, as it moves in deeper, you'll probably notice the moon glowing dimly orange, red or brown. Also notice that the edge of Earth's shadow projected on the moon is curved — visible evidence that Earth is a sphere (or, more precisely, an oblate spheroid), as deduced by Aristotle from lunar eclipses he observed in the fourth century B.C. It's almost as if a dimmer switch were slowly being turned down on the surrounding landscape and deep shadows of a brilliant moonlit night were beginning to fade away.

Across the western U.S. and Canada, the moon will already be partially immersed in the umbra. The low, partially eclipsed moon in deep blue twilight should offer a wide variety of interesting scenic possibilities for both artists and astrophotographers.

How to photograph a lunar eclipse.

The part of the moon that is immersed in shadow should begin to glow faintly, like a piece of iron heated to the point where it just begins to glow. The umbral shadow is not complete darkness.

The outer portion of a telescope or binoculars can reveal lunar seas and craters. The central part is darker and sometimes no surface features are recognizable. Reds and grays are usually the main colors in the umbra, but sometimes there are shades of brown and other colors.

The Japanese lantern effect is a phenomenon that can be seen several minutes before and after the total lunar eclipse.

The total eclipse begins when the last moon enters the umbra. It is not known how the moon will look during totality. The moon appears to be dark gray or black in some eclipses. It can glow bright orange during other eclipses. When the moon is completely obscured by the Earth, it is not possible to see it. The sun would be hidden behind a dark Earth and a red ring of sunrises and sunsets if a person stood on the moon during totality. Global weather conditions and the amount of dust suspended in the air can affect the ring's brightness. There is a bright lunar eclipse when the atmosphere is clear. The eclipse is very dark if a major volcanic eruption has injected particles into the stratosphere.

There was an eruption of a submarine volcano in the southern Pacific Ocean on January 15. Whether this eruption injected enough ash into the atmosphere to cause the upcoming eclipse to appear dark is a question that we won't be able to answer until eclipse night.

The moon will rise in a total eclipse for northwestern Oregon, the western half of Washington state, much of British Columbia and the Hawaiian Islands. Observers in these areas will have to wait until the moon has climbed above the east-southeastern horizon for their first view of the lunar disk. Observers in Hawaii probably won't see the moon until after it emerges from the umbral shadow.

The moon turns red during a lunar eclipse.

The moon is now shining between 10,000 and 100,000 times fainter than it was just a few hours ago. Because the moon is moving to the south of the center of Earth's umbra, the color and brightness of the moon's disk should be darker, with shades of deep copper or chocolate brown. The part of the moon closest to the umbra should appear bright with reds, oranges and even a soft bluish-white. Observers away from bright city lights will see more stars.

The entire constellation of bright summer stars and constellations can be seen to the north and east of the moon. In 1982, retired NASA astronomer Fred Espenak watched a total lunar eclipse with the moon in the same part of the sky.

The sky is dark during totality. The landscape has become somber. The moon looked flat before the eclipse. It looks like a ball suspended in space during totality.

The temperature on the sunlit surface of the moon was at a cool 261 degrees Fahrenheit. Because the moon lacks an atmosphere, there is no way that this heat could be retained from escaping into space as the shadow sweeps by. In just over an hour, the temperature on the moon has dropped to minus 146 F ( minus 99 C), which is 888-492-0 888-492-0.

The moon emerges from the shadows. The Japanese lantern effect occurs when the first small segment of the moon reappears.

Only those in the southeast part of the state will be able to see the eclipse. The moon will be below the horizon for the rest of the Great Land State.

The umbra should be devoid of any color now. As the dark shadow slowly creeps off the moon's disk, it should appear black and featureless.

The dark central shadow clears the moon's right-hand limb.

The show comes to an end when the last faint shading disappears from the moon's right portion.

The eclipse ends as the moon is completely free of the penumbral shadow.

If you snap an amazing lunar eclipse photo and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo, comments, and your name and location to us.

The instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium is Joe Rao. He writes about astronomy for a number of publications. Follow us on social media.