Most of the time, no one has to think about how the mobile networks we all rely on work. It won't surprise many to hear that some pieces are the latest tech and others haven't changed in decades. A startup called Eridan is aiming to replace one of the latter with a fundamentally different hardware approach that could make mobile networks more efficient.

There are cell towers that connect your phone to the internet wherever you look. The modem, the antenna, and the transceiver are the three big pieces of the net.

The modem has changed with the times and increased capacity. The antenna needs to reflect the new slices of spectrum being used for mobile data. The job of the transceiver hasn't changed much since it was first created.

We have begun to investigate the limits of that middle bit, which is a dinosaur in technological terms.

In the last 70 years, how the antenna has powered it hasn't changed.

The more power you put into them, the less efficient they are. As the number and complexity of signals has grown, the power used has only increased, and 5G transceivers are half as efficient as 4G ones, which were half as efficient as 3G. If you plan to cover all populated areas plus highways, the difference between the two will add up very quickly.

If you want to get everywhere, you have to take up 50 percent of the U.S.'s electricity.

Every wireless company has spent billions on something the industry has been looking for for 30 years. If you want everyone to have 5G without melting the planet, we are the only way to do it.

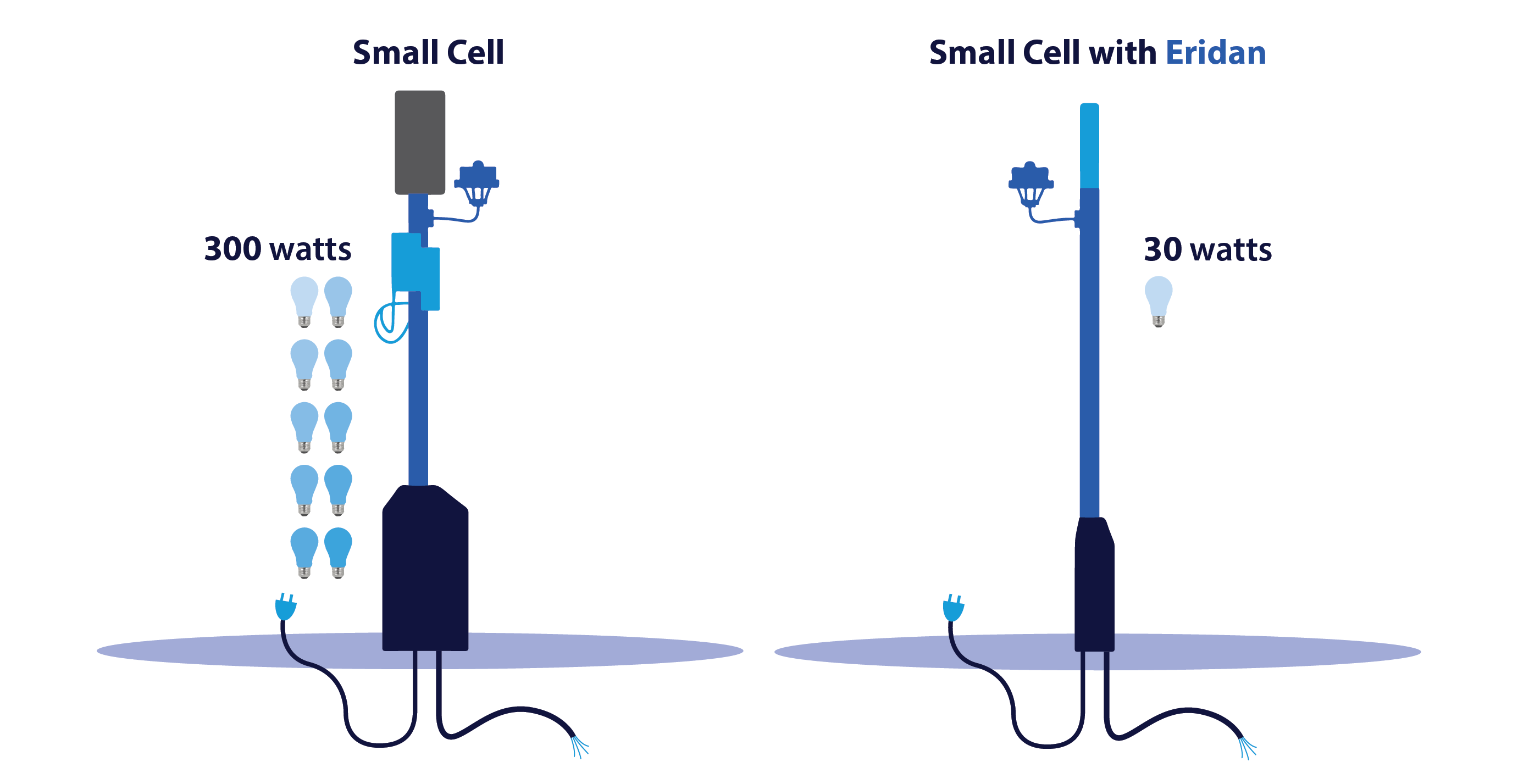

A standard pole-based cell and one using Eridan's tech.

What is it that Eridan has done? I was skeptical that a startup with limited means could leapfrog decades of research by some of the richest companies on the planet.

Kirkpatrick admitted that they cheated. The founder of the company, Earl McCune, who sadly passed away two years ago during the development process, was one of the people doing the research at the big telecoms where his approach never took off. They found a way to make the theory reality outside of the corporate structure.

After meeting during a failed recruitment to do related work for a large company, the founders decided they liked each other enough to pursue the concept on their own.

He recalled that they sat down with a bar napkin and a beer and then filled the think tanks. The first time we turned it on, it was the most perfect signal, because everybody's eyebrows went up. How are we going to explain this to anyone?

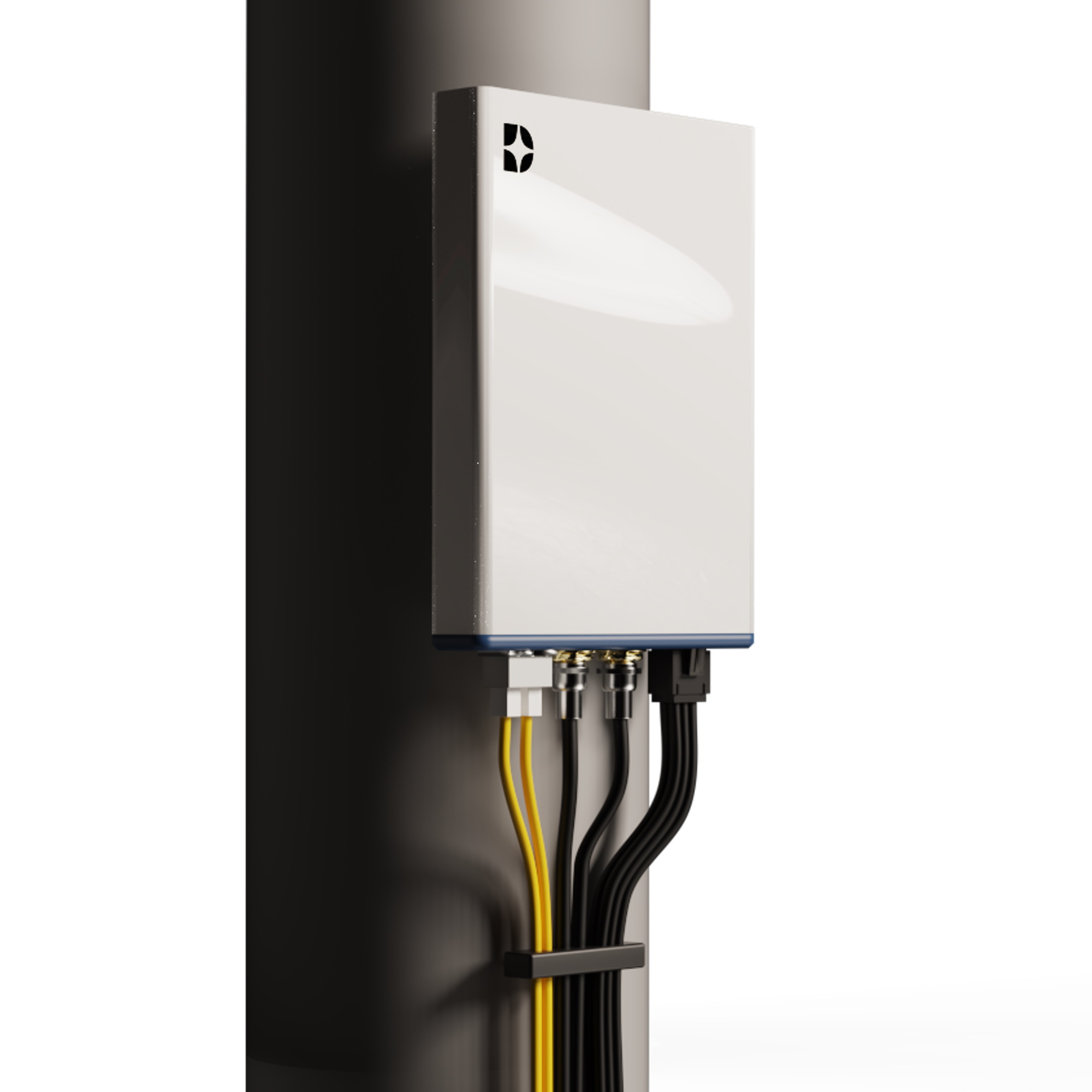

An Eridan unit might look on a featureless pole.

Going from vacuum tubes to transistors is one of the ways the advance is simple.

Since they're worried about cost and efficiency, they've made the best of a bad bargain: how dirty can you make the signal? He explained that this is fundamental to what linear amplifiers do. It is a hundred times smaller and a hundred times cheaper.

Earl was a savant of this kind of approach and wrote books on it. Dubravko Babi is a materials expert who focuses on gallium nitride, which is used in combination with Silicon to create high-efficiency chip architectures. They can make a jump from 10% efficiency to 50% with the GaN-Silicon combo.

They got a $5 million contract from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, thinking it could be used to shrink military radios, but soon realized the tech reached well beyond the defense category, and brought it to telecoms.

They have had trouble getting prospective companies to understand the qualities of the device because it is so different from existing infrastructure. When you light it up on a mast, it's all over.

He admitted that the infrastructure market is conservative. These companies pay huge sums to build millions of installations to serve hundreds of millions of people, and they tend to go with what they know works even if there's a newcomer out there that's better and cheaper. The pilot test at Fort Hood should show Eridan's 5G small cell capabilities, which should lead to commercial deployment around the end of the year.

The owners of the Eridan team. The CEO is wearing a pink shirt.

Beyond the threat of linear Amp reaching the theoretical limits of the amount of data they can handle is the further expandability of Eridan's tech. It would make 5G deployment cheaper and better, but what about the next upgrade?

We won't get into the technical details of the latest signal protocols, but you can think of it as equivalent to home internet bandwidth. The more bits you can fit in a given stretch of signal, the more data you can deliver, though as is always the case with wireless, the more risk there is that this increasingly complex and fragile signal doesn't arrive intact.

Going from analog to digital production of that signal has a huge effect on how effective a transmission is. The use of GaN allows the system to operate at high voltages, removing the need for an amplifier at all, further improving signal because amplifier amplify a dirty signal.

Eridan has shown in a lab setting that they can transmit a 16-bit, 64K QAM signal using an experimental 10-bit, 1024-QAM released by 3GPP. People who like wireless protocols will find that number very impressive.

The promise of being a major part of infrastructure that needs to be built out for a decade and more has clearly activated the check-writing portions of investors. Between today's B round announcement and an $8 million A round, Eridan has raised a total of $46 million. The A round was led by Social Capital.

The money will be used to hire up and make hundreds of millions of dollars of these things. It's not hard to imagine the likes of whom would benefit from this hardware, though he couldn't name the prospective customers. If you've heard them talk about 5G at some point in the last 5 years, you're probably on the list.

After the official demonstrations at Ft Hood next year, commercial deployment should start appearing. You probably won't notice anything, but that's kind of the point.