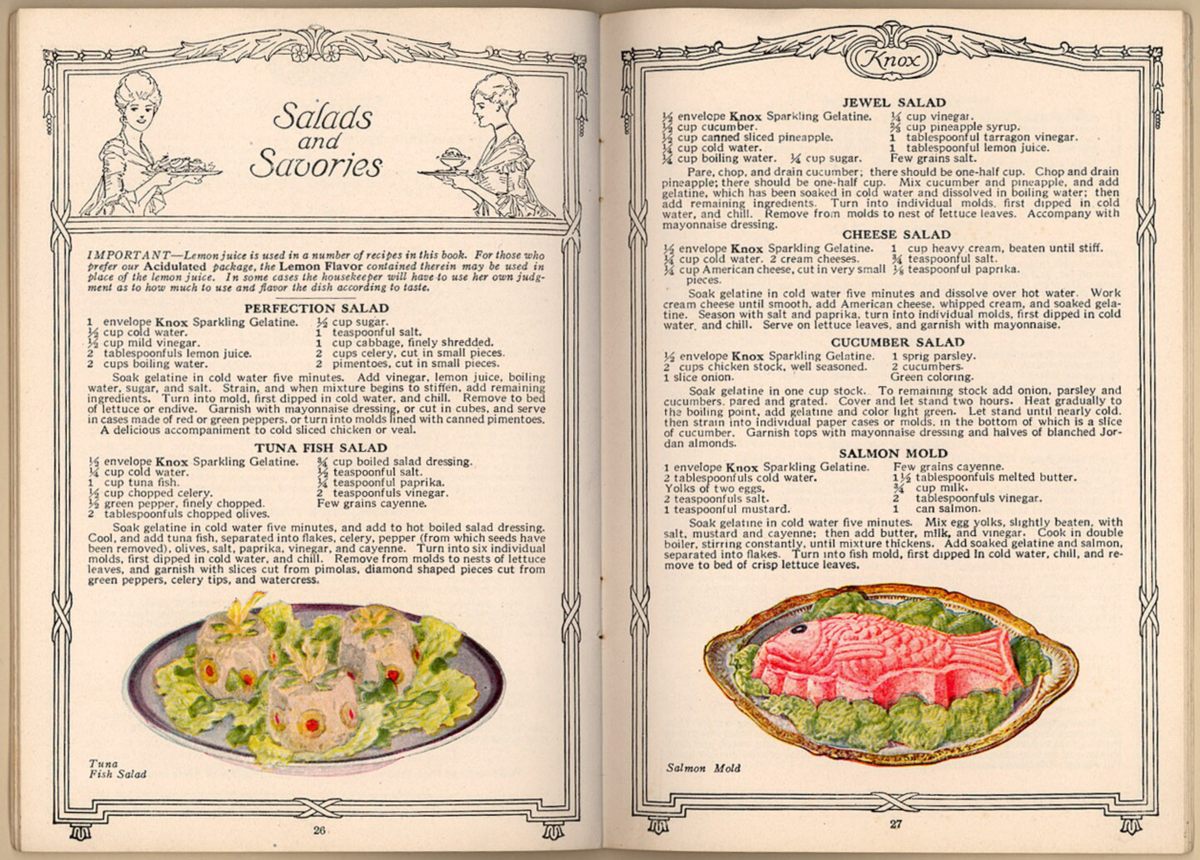

The lamb ribs are surrounded by nubs of green beans, hard-boiled eggs, and capers, all entombed in a flavorless, wobbling mass. A two-tiered tower harbors mayonnaise and asparagus. An acid-green, lime-flavored mound holds a can of tuna. The gelatin salad is a catch-all term for dishes sweet, savory, and everything in between.

The former food of the future is now a subject of ridicule and morbid fascination as it was once considered cutting-edge. Facebook groups like "Crimes against jello and vegetables and other mid-century transgressions" and "Aspics with threatening auras" collectively have tens of thousands of members.

The appeal lies in juxtapositions that feel wrong, whether it's a whole turkey in aspic from the 1920s or a portrait of Queen Elizabeth. It is what Freud would have called it, but it is also known as the cursed aesthetic.

pics were not always cursed. Despite their association with American food that went awry, the dishes are not originally American or particularly processed. Aspics held a place of honor on tables and banquets around the world for nearly a thousand years. The 10th-century Arabic cookbook Kitab al-Tabikh has a recipe for a saffron-stained fish that caught the light like a cut garnet.

THE GASTRO OBSCURA BOOKThe world needs to be tasted!

An eye-opening journey through the history, culture, and places of the culinary world. Order Now

Ken Albala, a history professor at the University of the Pacific, says that Gelatin is one of the few foods that goes so radical in and out of fashion. Albala is the author of more than two dozen books on food history and culture, and he chronicles the story of his current obsession in his upcoming book, The Great Gelatin Revival: Savory Aspics, Jiggly Shots, and Outrageous Desserts.

Albala says that it is out of fashion because it was democratized with the brand.

Albala has earned the nickname "Jiggle Daddy" over the last three years for his willingness to attempt all sorts of feats. He created a mask with interwoven strips of meat and two inverted octopuses in sake- infused Jelly, which had their curled and open maws exposed.

Albala has earned the nickname “Jiggle Daddy” for his willingness to attempt all sorts of gelatinous feats.

Albala discovered his Jiggle family in groups such as Facebook's Show Me Your Aspics, which has more than 45,000 members. He was horrified when he found the page, but immediately fell in love with it. I made another one.

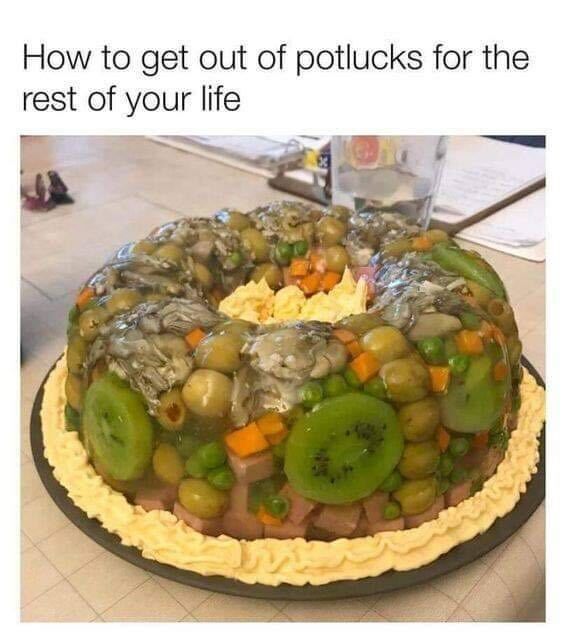

Most people in this particular internet subculture enjoy unpalatable flavor combinations. The aspic set in a Bundt pan mold, swimming with canned oysters, olives, frozen peas, carrots, and spray cheese is one of the more popular meme that has been circulating as of late. It was called "How to get out of potlucks for the rest of your life."

Albala says that the demographic that is not looking into this for kitsch value is the deranged. If there is a really sick combination, they love it.

Gelatin's descent into the meat-laden molds that evoke disgust and delight is a fundamentally American one. There was nothing accidental about them. The rise of the nation's industrial food complex and its obsession with class, gender, and the constant pursuit of more are reflected in midcentury gelatin salads.

Meat and seafood in an air-tight dome was an effective method of keeping harmfulbacteria at bay. The concept was quickly adopted by cooks in Europe. The bones and heads of river fish were popular options for binding agents, but they were not the only options. The dried isinglass from the swim bladder of a sturgeon is used to makerated hartshorn.

Bonnie Morales, co-owner of Kachka, says that cooking bones and joints and things that have a lot of natural gelatin is more of a linear path than the bastardized version of that. People think that meat aspic is crazy, but in reality it is an animal product.

kholodets has a special place on Christmas and New Years tables in Ukraine. For Olesia Lew, head chef of Veselka, a Ukrainian restaurant in New York, kholodets has always been an expression of love, as well as a visual medium for the cook to show off.

Aspics were once the food of kings and emperors because of the opportunity for showmanship. One of King Henry VIII's favorite dishes was a jar of red wine. The glory of the 18th-century French and Russian courts were the elaborate aspics of Marie-Antoine Car. Tafelspitz-Sulz, an aspic with boiled beef, was a favorite dish of the Austrian Imperial family at the grand Hotel Sacher in Vienna in the 1800s. You either had time on your hands or the capital for domestic servants or professional cooks if you had an aspic. In other words, aspics were exclusive.

Many wealthy Europeans brought their cooks with them when they moved to the Atlantic. At the end of the 19th century in the United States, there was a certain air of Continental elitism. In an 1874 portrait, Jules Harder, the chef at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, holds an aspic crowned with a whole lobster that has been impaled with a miniature sword. Harder's were labor intensive, requiring either soaking whole gelatin sheets or making a stock from scratch.

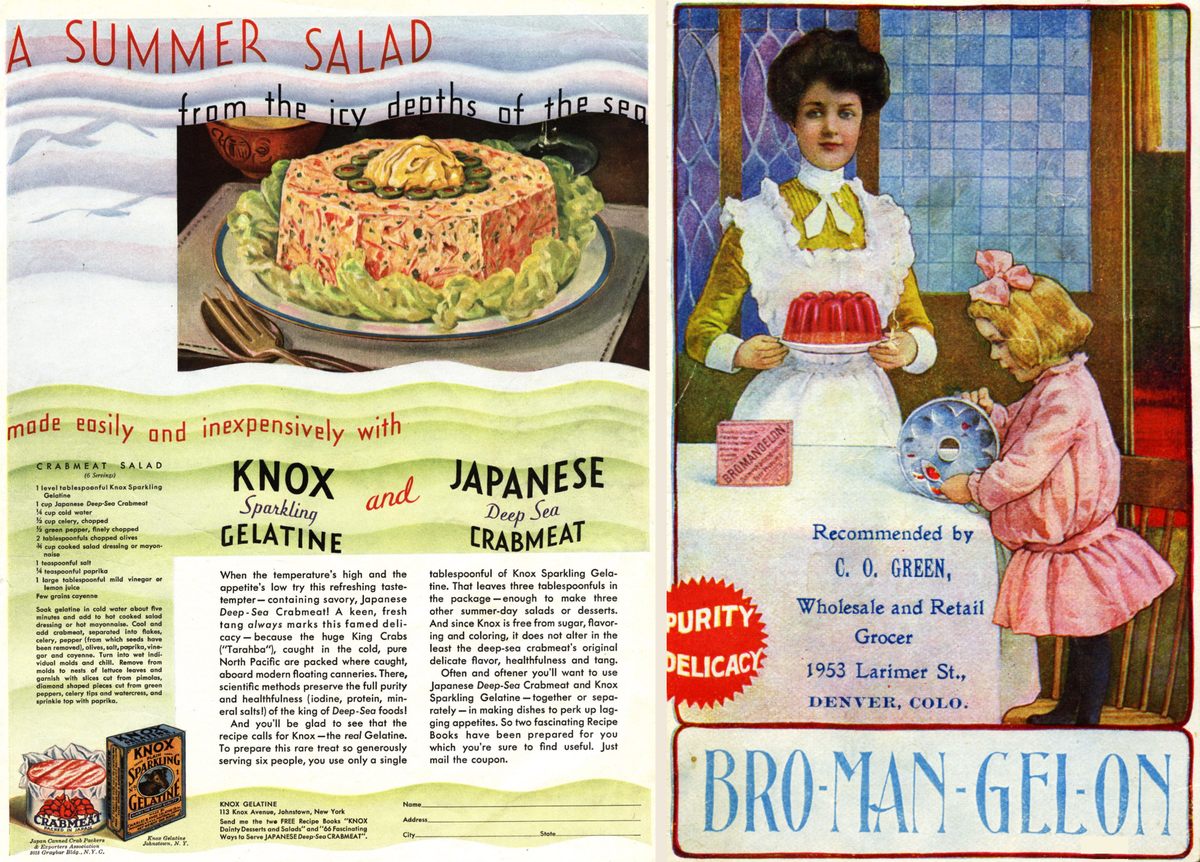

Sarah Tyson Rorer, an American food writer and early member of the domestic science movement, wrote a letter to the company in 1893. Women were already compacting their salads into aspic form, but soaking the sheets was a pain. What if the company came up with a powdered option? A powder that dissolved instantly was on the market. The public recipe contest in 1905 for creatively molded gelatin dishes capitalized on the product's malleability. The inspiration for American housewives to feature their own centerpieces at their next dinner party came from the recipes Fannie Farmer served as a judge.

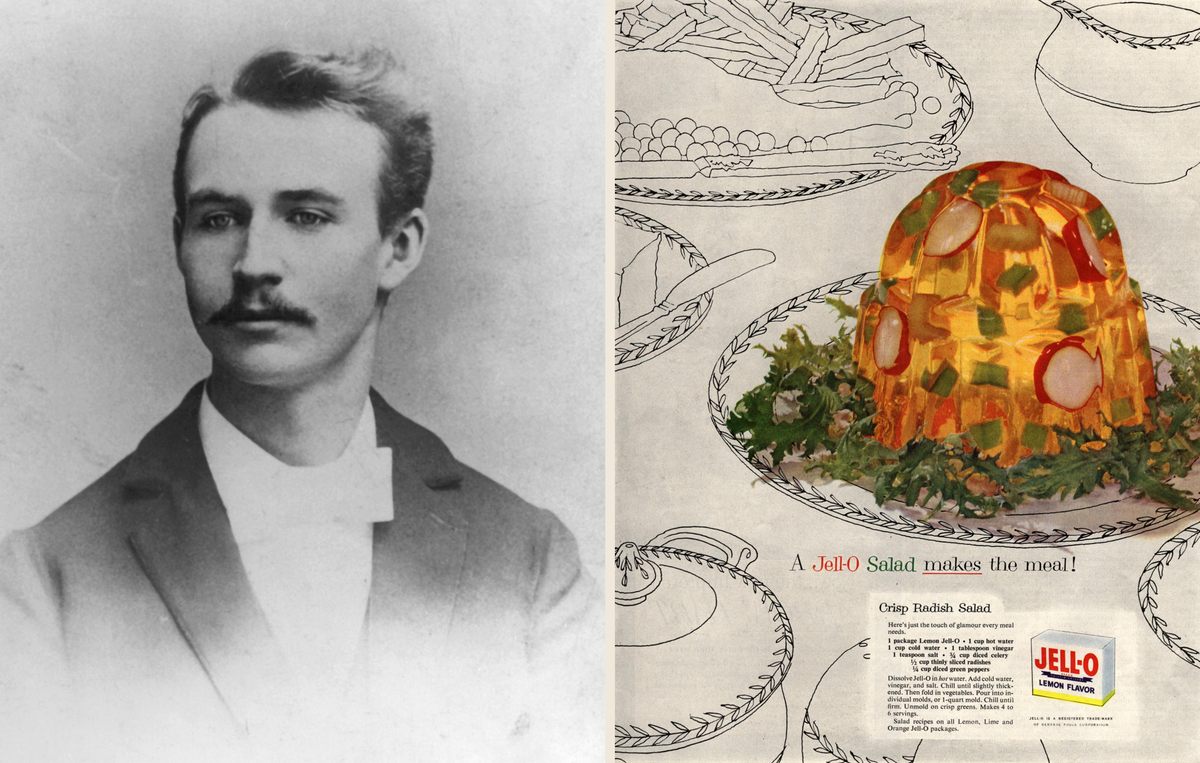

It didn't take long after the arrival of Sparkling Granulated Gelatin for another innovator to find a better way to brand it. Pearle Wait, a New York carpenter, patented the name in 1897. Wait began to make lemon, orange, and strawberry options. Orator Woodward, the inventor and founder of the Genesee Pure Food Company, bought the patent for Jell-O for $450 two years later.

When my great-great-great-uncle bought the patent to Jell-O, he initially had trouble selling it. It was inevitable that a new food product would have a gendered marketing strategy. The brand leaned in more than most, as it did not feature men in its advertisements until well into the 1990s.

American women have been taught to be caretakers. The early advertisements promised convenience, a way to put something that felt high-class on the table with their ever-shrinking time. According to Rowbottom, it was portrayed as a way for them to take care of their duties in the home and still manage the million other things they had to do. Woodward's annual sales were more than $8 million within two years.

This whole phenomenon is a poster child for consumption. "It's food that looks like something spectacular, and I spent years researching the rise of gelatin salads for my book, Perfection Salad, because of my total bewilderment as to why any rational human being would want to make or eat a salad."

There is a combination of social mobility and rising incomes for people moving into the middle class. For a long time in the early 20th century, a woman could display that she had both the time to prepare and store her salads, and a fridge to store them.

Gelatin was not part of any sort of tradition. The General Foods Company, which was swallowed by the tobacco conglomerate Philip Morris Companies in 1985 after it was sold to the Postum Cereal Company in 1925, used the test kitchens at the Knox Company and the Jell-O Company. Lime, lemon, and other saccharine options were used in lieu of unflavored gelatin as new artificial flavors were introduced. The laboratories would have an outsized influence on American diet for decades to come.

They came out of someone's imagination, not from a banquet. From the 1920s to the 70s, popular recipes included an amalgamation of cabbage, Miracle Whip, and canned pineapple set in both lemon and lime.

No normal person would think of these things in the kitchen. What is the goal here? It's not possible to make something that tastes good.

The point was never flavor. The domestic sciences movement started in the late 1800s by women who believed that if they could reform American eating habits, they could reform Americans.

“They came out of the fevered imagination of someone in a test kitchen, not from some medieval banquet.”

Hundreds of women worked in 53 test kitchens for General Foods. Although most of them worked in anonymity, they were dedicated to changing America's relationship with food. The General Foods Kitchens Cookbook was first published in 1959 and was written for an average American family. The women leading the domestic science movement wanted to create food that was modern, clean, and efficient.

The idea was that everything your mother did was outdated. The new science for women was domestic science. You had scientific motherhood and cooking.

The over-the-top nature of some of the salads may be due to the creativity of the women who invented them. In her book The Secret History of Home Economics: How Trailblazing Women Harnessed the Power of Home and Changed the Way We Live, Danielle Dreilinger points to leaders of the domestic science and home economics movement.

They were trained in science and chemistry, so you don't want them to go to home economics.

The result of giving brilliant women no outlet beyond the domestic sphere was corporate test kitchens full of minds that, in later decades, might have ended up in laboratories, and they were able to use their knowledge of chemistry into jello and cake mixes. Making women's work like cooking more scientific was an attempt to escape from its confines. Unlike messy, freeform cookery, gelatin salads required precise measurements. The diner didn't have to clean their fingers because the food appeared orderly and contained.

The women of the test kitchens made these meals visually stunning. Glossy, full-color magazines were in homes all over the country by the 1910s and 20s, telling women what kind of life they should strive for. No matter what it tasted like, a mold on the cover of Gourmet was guaranteed to turn heads.

Some of the preparations were seen as high-class, something you would achieve to look sophisticated and chic. In the early 1900s, recipes like Fannie Farmer's Ginger Ale Salad would appear in Woman's Home Companion, a magazine for the upper-middle class. It gains a class identity from the tables it sits on and the people who serve it.

The hardship of the Great Depression and World War II led to the creation of American Jell-O salads. When Americans needed to save money, the company marketed its product as affordable, and when they didn't have time to cook dinner, it was so easy a child could do it.

The less the brand sold the idea of accessibility, the less it was seen as high-class. The food spoonfed to hospital patients was an approved substitute for real cake by the 1990s. Sales of the candy fell by $371 million between 2009 and the present. The regional pockets of the Midwest and American South were the places where meat salads were still popular in the 70s and 1960s. Utah has held on to its unofficial title as the nation's Jell-O Belt for its enduring popularity there.

It is constantly changing and remaking itself.

Ken Albala is willing to bet that the pendulum of history is going to swing back in American's favor.

The internet and high-end creations of chefs are the two directions in which that iteration will go. It's a perfect fit for the visual media that dominate American popular culture. Albala says our distrust of science and technology is waning.

The American gastronomy is no longer paranoid about anything coming out of a laboratory. Restaurants are proudly announcing the presence of monosodium glutamate, a synthetic version of a naturally occurring compound, in dishes and cocktails, and tech-based meat alternatives are booming.

Albala says that members of Show Me Your Aspics, who are mostly women and nonbinary people in their thirties, may lean into the weird of aspics, but a number of chefs are taking them more seriously. Part of that comes from the fact that food is very popular on social media platforms. In Brooklyn, you can buy boozy jelly cakes for $80 a pop. The book cover of Gastro Obscura was covered in jelly-cake.

Other chefs in the United States are looking for inspiration from cultures that didn't go so crazy with their food. Jellied sweets from Southeast and East Asian countries are gaining popularity in the US. The chef at the restaurant is using fish-based stock in his aspics.

aspics had some bad reputation here or were seen as outdated, Delaroque says. His creations are impossible to get for the most ambitious home cooks. The dishes like his aspic de homard en bouillabaisse, with a clarified rockfish and lobster shell stock fragrant with herbs and fennel and topped with a whole lobster tail, are more in line with what chef Marie-Antoine Carême might have presented to

Delaroque says that the visual component is important because at the end of the day, people are not sure about a meal unless it looks great. The aspics have a lot of interest.

Home-cooked food is not the same as restaurant food. The aspics attracting attention on Facebook,Pinterest, and TikTok are incredibly demanding in terms of time and labor, which may be part of their appeal to the average amateur cook. The domestic scientists wanted to bury the past in order to push society towards the future, these modern-day aspics-makers want you to know that their creations, both the deranged and delicious, are decidedly not your grandma's Jell-O.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.