One species of trilobites, which looked like giant, swimming potato bugs wearing Darth Vader helmets, would come together for a hug, according to a new study.

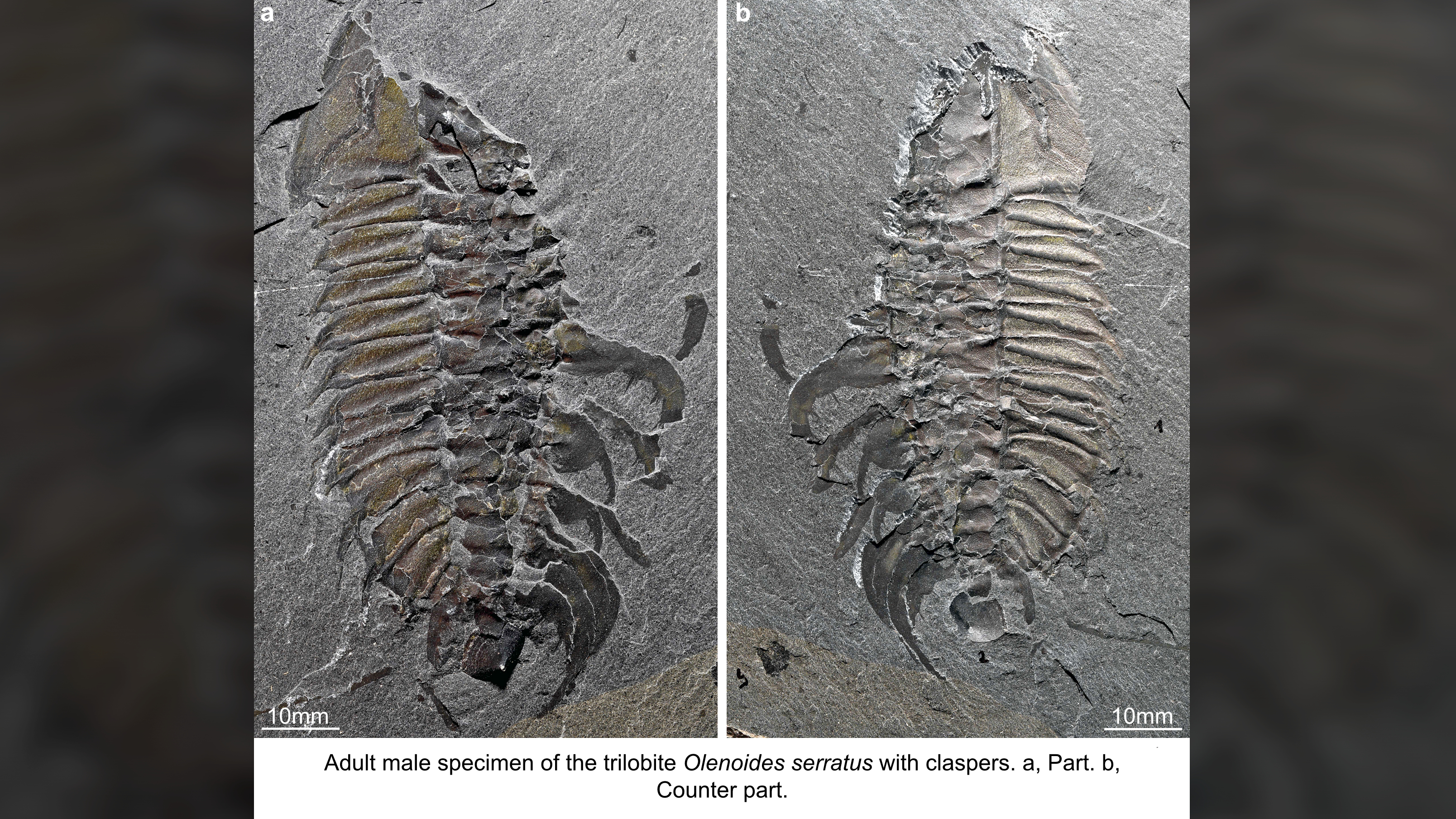

A scientist discovered an extraordinary fossil of a trilobite species that lived about 500 million years ago. The researchers said that the fossil showed a pair of short appendages on the underside of its midsection. A male O. serratus would mount a female from above, using the claspers to hold onto her body, in order to get her in the best position to have sex.

The male is in the right position when the eggs are released if he holds onto the female. It is a behavior that will increase the likelihood of successful sex.

Why did trilobites go extinct?

There are more than 20,000 known species of trilobites that were on Earth for about 270 million years before they went extinct. For more than a century, researchers have known about this species, O. serratus, after its fossil remains were found in the Canadian Rockies.

Losso said that scientists have mostly focused on the O. serratus specimen found in the early 1900s. Losso found a fossil at the Royal Ontario Museum while he was looking at this beastie.

I had to look at every single specimen, so I came across this one, and it was weird. That is not what these appendages are supposed to look like.

Losso said that trilobite fossils rarely preserve the legs. She said that only 38 of the 20,000 species have fossils with preserved appendages. She said it was remarkable that this specimen preserved the shorter appendage pair at the midsection.

She said that it is already a cool trilobite because it has appendages.

She said that the leg pairs in front and behind it are different. The trilobite's other legs may have helped the predator shred its food, but these short appendages don't.

The trilobite has a pair of short, slender and spineless appendages at its midsection. Losso and his co- researcher at Harvard University compared the appendages of O. serratus with those of living arthropods.

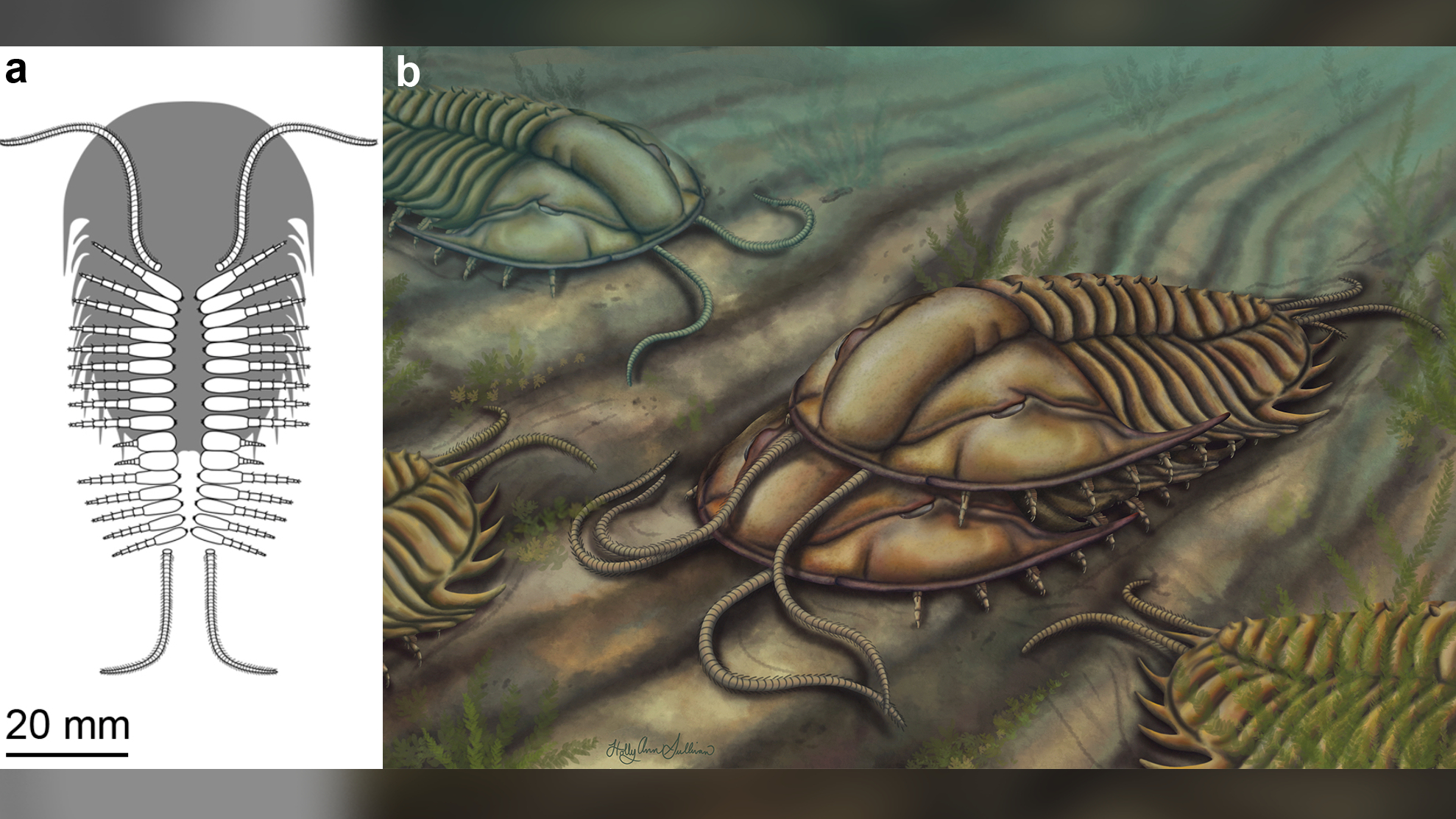

Losso said that the weird appendages were likely claspers. It is likely that the male would go on top of the female with his head lined up with her trunk, so he is offset more toward the back. The appendages of the male would line up well with the spines, so the claspers could grab onto them.

Lasso said the males likely used their claspers to hold onto her tail.

Lasso said that the specimen definitely does not have claspers.

The horseshoe crabs are very distantly related to trilobites.

In horseshoe crabs, males will shove each other off, Lasso said. The males end up hurting each other and sometimes they rip off appendages because they are all trying to get a position on the female when eggs are released.

What is the largest arachnid?

She said that it was possible that O. serratus was equally competitive. She cautioned against overpolating this behavior to other trilobite species, as they had a wide array of habitats and body shapes.

Lasso said that this is the first time they have seen a really significant specialization of appendages in trilobites.

Greg Edgecombe, a researcher of arthropod evolution at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science that the study makes a convincing case that the modified legs are biological variation and not regeneration after being damaged.

The idea was that the trilobites came together as a group. We can add more detail about the claspers that some trilobite males had.

The study was published in the journal Geology.

It was originally published on Live Science.