Policymakers are talking about the possibility of all physical money going the way of the copper coin.

The penny will be out of circulation in the federal budget.

The photo was taken by Phil Carpenter.

The penny was a regular part of Canadian cash for over a century, sitting at the bottom of wallet, gracing tip jars, and being fished out of pockets to support local charities.

The penny was taken out of circulation in the 2012 federal budget after a finance committee study found that the coin was too expensive to produce. The end of an era was marked by the last penny pressed by Jim Flaherty.

Canada could be on the verge of a far more radical shift in payments, as policymakers talk openly about the possibility of all physical money going the way of the copper coin. Lessons from the penny could help smooth the transition. Killing off a coin that most people have stopped using sounds simple, but it isn't.

Marie Lemay, chief executive of the Royal Canadian Mint, said in an interview that it will be valuable.

Jim Flaherty had the last pressed penny.

The photo was taken by Ken Gigliotti.

The decision to end the penny was made ten years ago, at a time when Canadians are less likely to carry cash and coin with them.

The Bank of Canada accelerated its research on digital currencies, including a virtual dollar, last year.

Carolyn Rogers, the central bank's senior deputy governor, said this week that she could see Canadians giving up cash altogether in the future.

The coin management system that helped guide Canadians into a post-penny economy is helping everyone transition into the digital economy.

Some people cling to a unit of payment even as the majority moves on, which is an important lesson from the penny's demise. accessibility and universality are central to government tender. If a critical mass of Canadians want to keep using cash and coins, they should be able to do so. The Mint has learned how to make a smooth transition after taking the penny out of circulation. Lemay said her agency has become an expert at determining where there is demand for coins and ensuring there is enough supply in those places.

She said that it was necessary to have a view into where demand is and to be able to move them around to make sure that people are able to access coins.

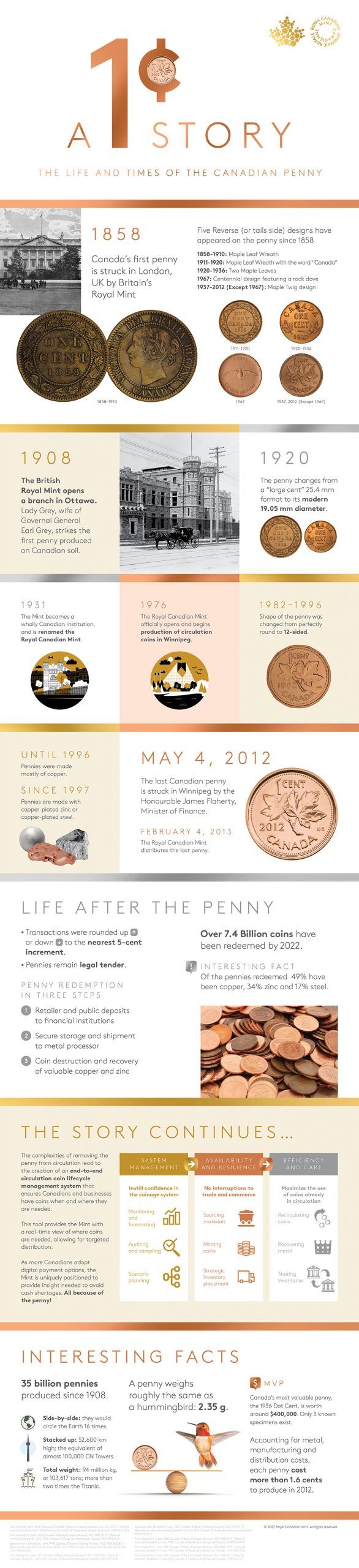

Before the penny became a case study in how the Mint will help bring about a world of digital payments, the coin had its own vibrant history that shows why some may have been reluctant to see it go.

The British Royal Mint adorned the penny with a maple leaf wreath when it was first struck in 1858. It wasn't until the 1910s that the name Canada crossed its face.

The design and makeup of the cent went through many changes over the years, including the 1936 DotPenny, a collector's item that came about as Edward VIII abdicated.

A penny from 1936.

The photo was taken by Heritage Auction Galleries.

To avoid a production gap, designers went with the likeness of the previous monarch, George V, on the coin, because work on a new design for Edward VIII or his successor George VI hadn't yet been finished. Due to an over-production of pennies, most of these coins were melted down and only three remain, one of which is currently being auctioned for $400,000.

The 1936 DotPenny is an example of the value of the coin management system. The old 1936 cents became obsolete when the new George VI pennies were ready. Think of it as a sobering lesson.

The penny is the most fractional legal tender in the Canadian economy. In 1976, the Royal Canadian Mint opened its circulation and coin production centre in Winnipeg.

Transactions were rounded up or down to the nearest five-cent level after the penny left Canadian circulation. The Mint's coin-management system evolved.

The Royal Canadian Mint has pre-pressed coins.

The photo was taken by Brent Lewin.

Canada's unique approach to coin management allowed for the removal of billions of coins from circulation relatively painlessly, according to Lemay.

We work with the financial institutions, the armoured car carriers, and we monitor the coin use across the country in real time, and then we use that information to estimate the requirements we forecast.

The Mint had to iron out details months in advance to pull the coins out of circulation, ultimately using a network of armored trucks to collect billions of pennies and flatten them to extract their base metals, rendering them useless as legal tender in a process called demonetization.

More than 7.4 billion coins have been redeemed to date, the bulk of which were brought in during the first three years after the coin was taken out of circulation.

More than 7.4 billion coins have been redeemed.

The photo was taken by Gord Waldner.

In the olden days, the penny's life and death illustrated Canadians' relationships with coins, as reflected by the senior director of the circulation team at the Mint.

The Mint and the Bank of Canada have been conducting surveys to find out how Canadians use money. Canadians with lower incomes are more likely to use cash, and rural communities are more cash-reliant than city folk.

The Mint's mandate of providing enough coins to the communities that rely on them the most is informed by keeping track of attitudes towards coins. Anthony Rotondo, Canadian circulation senior manager, said that these surveys became important for mapping out a post-pandemic cash economy and whether Canadians would still rely on cash and coins to the same degree.

The country may have moved closer to a cashless society because of the rapid growth of e- commerce and the use of digital money. According to a survey, roughly eight out of ten Canadians plan to use cash after the swine flu.

When Canada gave up on the penny, the Mint's chief executive said the shift to digital payments is similar. She said that the Mint's role is to make sure cash-reliant Canadians have access to it for as long as they need it. She said that there are a lot of Canadians who don't have cash in their pockets, so we have to make sure that we don't leave anyone behind.

Understanding the penny's past and how the country moved on from the copper coin is another step in the direction of what relationship Canadians will have with their money in the future.

I think that the future of the country will be the coexistence of cash and digital payments and currency.

Email: shughes@postmedia.com