We can't help but think about parallels to human music and language, since we hear birds more than ever during the Pandemic. The clanks and buzzes of Song Sparrow songs are linked by a sentencelike structure and a cheery whistle.

Birdsong is defined as the long, often complex learned vocalizations birds produce to attract mates and defend their territories. Bird calls are innately known and used for a more diverse set of functions, such as signaling about predator and food. The definitions are not clear-cut. Some species have simpler songs. I mean the longer, more complicated sounds of the bird as opposed to the short sounds of the bird.

The way in which birds strike our ears is reflected in the terminology used to talk about it. When researchers analyze bird song, they usually break it down into smaller units called notes or syllables. We group the syllables into phrases or motifs that have rhythms and tempos. We can measure important aspects of song, such as the number of syllable types in a bird's repertoire or the patterns in which phrases are arranged. These descriptions are similar to the way we mark the relations among words and notes in music.

What do the birds think about the features? How does it sound to them? Recent research done by my colleagues and I has shown that the sounds of birds do not sound the same as they do to us. Birds listen to their songs in a way that is beyond the range of human perception, and that is by listening to the acoustic details in the songs.

Birds hear song differently than we might think. Birds in the wild can be used to test perception in a variety of ways. Many birds respond to a song of their species being played by looking for a territorial intrusion, flying around the sound source, and making threatening calls. Researchers can learn which features are important by comparing responses to natural and manipulated songs. In the pre-digital age, they would record a song on a tape recorder and then use magnetic tape to create manipulated songs. Digital recording equipment and sound-editing software make it easy to make such changes.

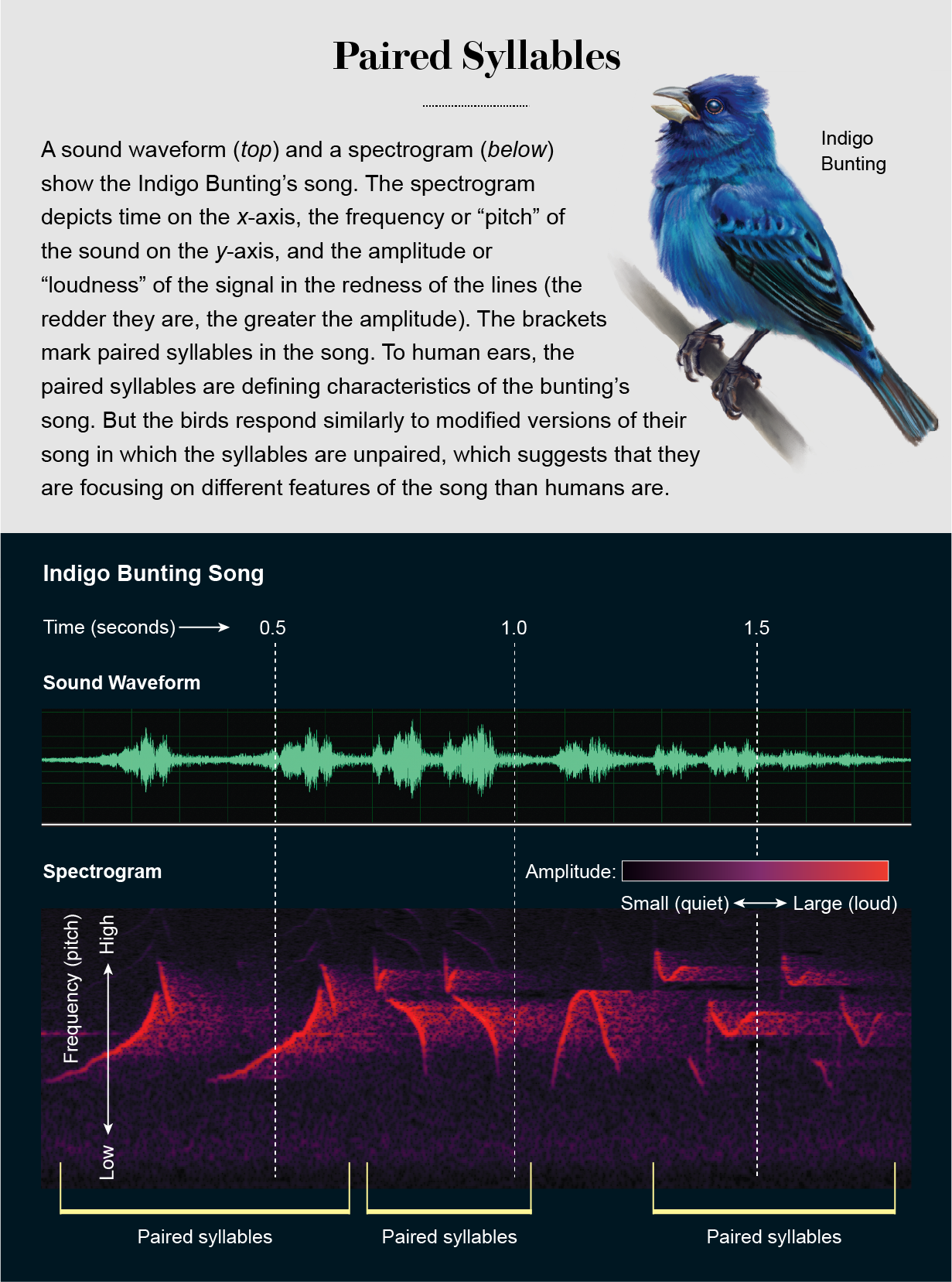

In the 70s, Stephen T. Emlen studied song perception in the indigo bunting. The vibrantly blue males of this species deliver songs consisting of syllables that they almost always utter two at a time. When describing a song, ornithological field guides call attention to the pattern of pairs of vowels, and it is easy to see in a spectrogram, a visual depiction of the signal over time. The perceptual equivalent of frequencies is pitch. When Emlen played a modified song that was notpaired to the birds, they responded with the same intensity of territorial response they exhibited when they heard the natural song. The pattern of pairs of notes is not significant for the birds in terms of recognizing fellow species members. It would be different if the Indigo Bunting wrote a field guide description of its own song.

Testing how birds perceive song in the wild has its limits. When you want to start your experiment, a bird could be out of earshot. Researchers can test hearing in birds in the laboratory. When you go to the doctor's office to have your hearing checked, you are told to raise your hand or push a button if you have heard a sound. A similar approach is used by researchers. We can ask the birds if they hear a sound or if it fits into a particular sound, so we teach them topeck a button on the side of their cage.

There are many similarities between songbirds and humans, including thresholds for hearing differences in pitch or detecting gaps between sounds. They have shown that birds and humans can't hear the same things.

Birds do not perform well on recognizing a melody shifted up or down in pitch. If the tune is played on a piano in higher or lower register, we will still recognize it. Experiments done in the 1980s and 1990s show that when the pitch of a sequence changes, the tune sounds different. Birds' perceptual experiences may be different from ours.

Subsequent studies have supported that hypothesis. European Starlings can recognize the sounds of a certain sequence but only when all the details are removed. The importance of those fine details to birds is highlighted in that work.

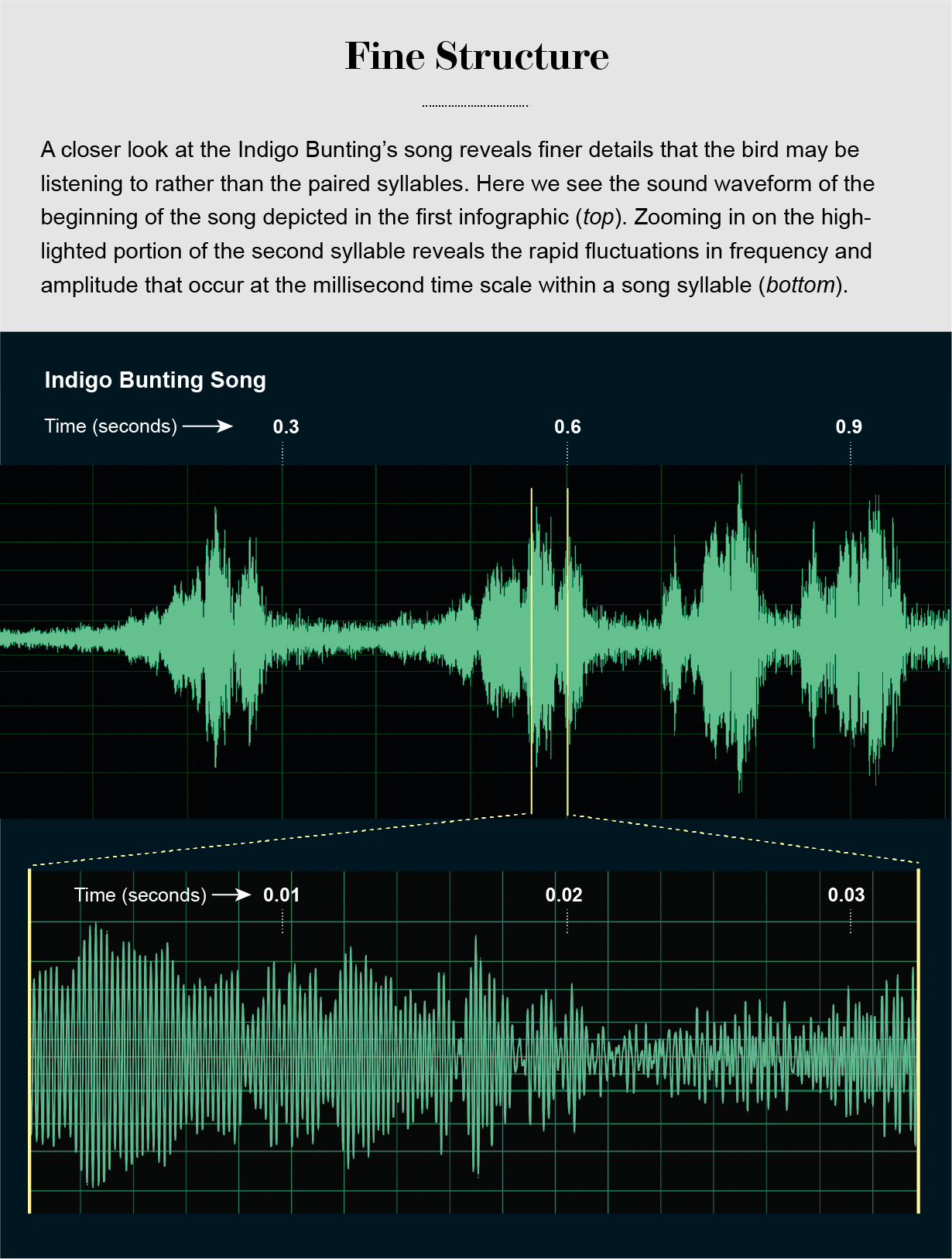

The envelope and fine structure are levels of description. The envelope is made up of slow fluctuations in the amplitude of the signal, whereas the fine structure is made up of rapid fluctuations. A sound's fine structure is how it changes at the millisecond level. Fine structure is not readily visible in sonograms or spectrograms, which makes it hard for people to visualize song. These acoustic details can be seen when you zoom in on the song syllable.

The University of Maryland helped to pioneer the study of fine structure in birds. For decades he and his colleagues have been assessing birds ability to detect it. They tested birds and humans on distinguishing sounds in fine structure. The bird species they tested performed better than the humans did. The birds were able to hear smaller differences in structure than the humans could. The mechanism behind the birds' sensitivity is unknown, but it may be related to the fact that their cochlea is slightly shorter than ours.

When I was in graduate school at the University of Maryland, I didn't think much about fine structure. I was looking to find language like grammatical abilities in birds. The key to understanding what birds are saying in song may be found in the acoustic details, rather than the sequence in which they occur.

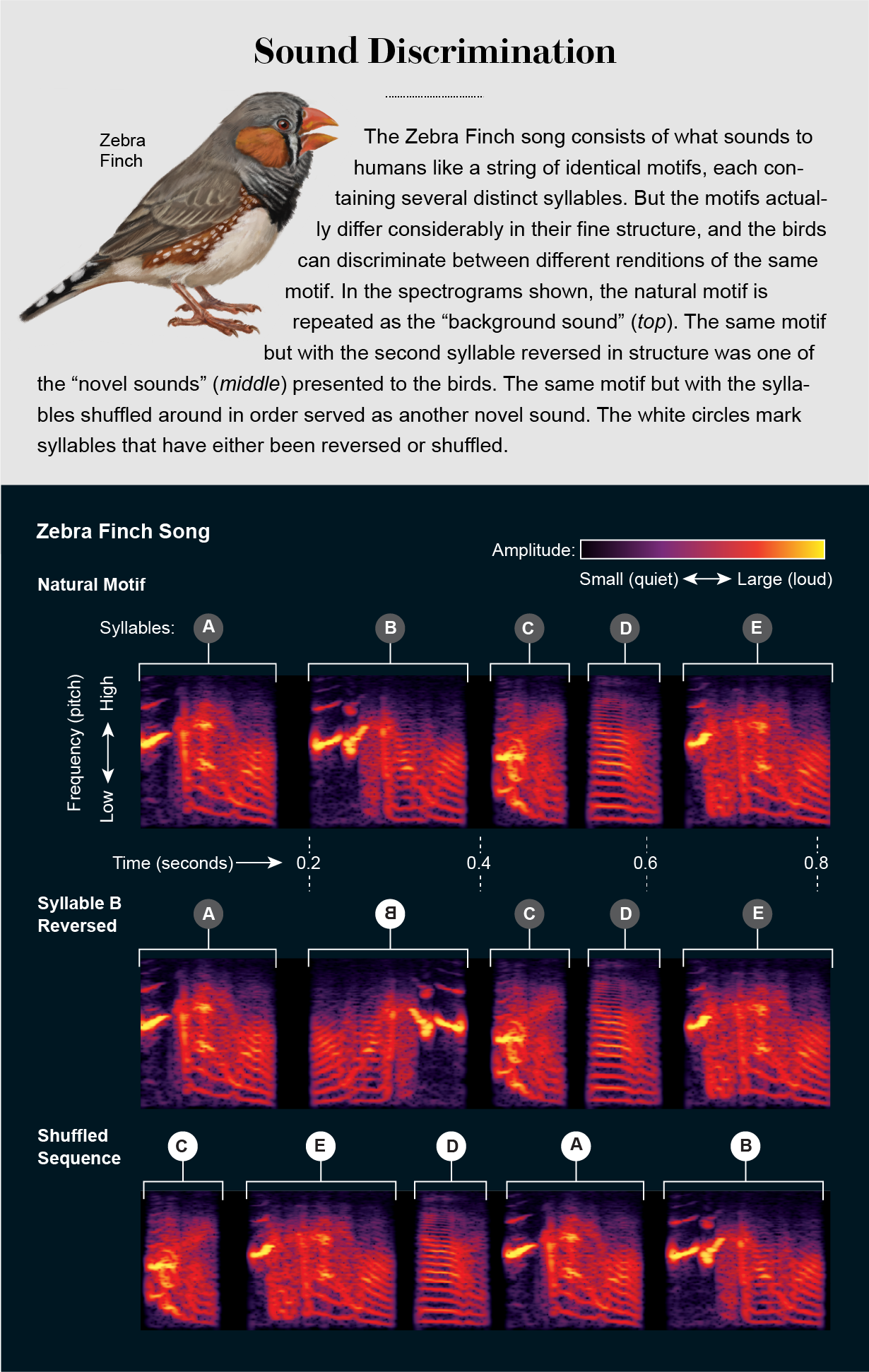

The grand champion of the birds was the zebra finch. This small, lively songbird native to Australia is the most popular species for lab-based modern birdsong research because it both sings and breeds prolifically in captivity. Its song is relatively simple, consisting of a single motif of three to eight syllables repeated over and over again, usually in the same order. The simplicity of the song makes it easy to study. One might think that both levels of the song are important in perception because the males learn both the syllables and sequence from their father.

The idea was tested in a study that looked at how well zebra finches hear the difference between natural song motifs and motifs where syllables are temporally reversed or shuffled in sequence. We trained birds to distinguish between sounds. They listened to a repeated sound and then pressed a button to start a trial. If a birdpecked a button when the sound was different, it counted as a correct hit, and the bird got a food reward. The lights in the chamber went off if it pecked that button when the sound was the same. The birds were evaluated for their ability to discriminate between the repeating sound and novel sounds. The birds were just trying to make money.

It is difficult for our human ears to detect reversed syllables, but the Zebra Finches did a good job at discriminating shuffled syllables. One of the main things that changes when you reverse a syllable is fine structure, so it's not surprising that the birds knocked it out of the park. Their difficulty with sequence differences is unexpected, not only because those changes are easy for humans to hear, but also because the males learn to produce song syllables in particular sequence. Their difficulty in seeing shuffled syllables may mean that they don't have much information for communication.

We wondered how fine-structure perception was relevant for natural song communication after seeing the results of the artificially modified songs experiments. The birds never produce reversed sounds. How well birds hear natural acoustic changes in song was the next question we asked.

My colleagues showed in a paper that the fine structure of one another's calls can carry information about sex and identity. To examine their perception of fine structure in song, we took advantage of the fact that the song bouts consist of a single motif repeated over and over with the same in the same order, or at least researchers think of them as the same. There are small differences in how a given syllable is said. The finches can hear the differences between different renditions of the same song.

This result shows that the Zebra Finch song doesn't sound the same to birds as it does to us. We think that they could be able to see a lot of information beyond what our ears can see. It is reasonable to assume that other birds with songs that sound repetitive to human ears will also have the same powers of perception.

You might be wondering if the small acoustic fluctuations in song are random or accidental, like the pitcher's curve toward home plate. The bird voice box may be the key to fine structure. Humans use a single source at the top of our neck to make sounds that are used to make speech. Birds use a two-branched structure that sits atop the lungs called the syrinx to produce sound. It has two sources of sound, one from each branch. The songbird syrinx has muscles that contract faster than any other muscle. The birds can control it in addition to seeing it, since they aren't producing fine acoustic variation by a slip of the beak.

Birds listen to song differently than we have thought. When we listen to music and speech, there are certain elements that are important. When we hear it, we can project them onto it. Birds don't seem to care about differences in sequence. Some species can't hear simple changes. When these kinds of tricks are used in music or speech, they completely disrupt the message. Birds seem to be listening to the acoustic details of individual song elements independently of the sequence in which they occur. They hear more than our ears can hear.

It's better to think about how the birds sound than it is to think about human language or music. When I learned to follow a Charleston in my swing dance class, it was important to get the sequence right, like when we learn a dance routine. The structure of an individual move can fall apart if a transition is messed up. Someone watching a dance doesn't get much information from the order of the moves. The acrobatics, rhythm and variety of the movements are what the audience is focused on. It might be the same for birds. Getting the sequence right is important for getting the moves right. What is most important for the bird is the individual moves themselves.

There are some parallels between human speech and music. In the animal kingdom, the ability to take heard sounds and reproduce them as humans do in speech and birds do in song is very rare. Chimpanzees do not seem to be vocal learners, nor do any other primate. bats, whales, elephants, seals and sea lions do not achieve the same level of vocal mimicry as humans and some birds. The neural pathways and mechanisms that control vocal learning and production in songbirds and humans are a product of convergent evolution. We can learn a lot from studying birds. The songs they produce don't seem to be what we would think of as music or language.

We don't know a lot about how birds perceive music. We don't know if the information that bird calls convey is relevant in the fine structure of the song. We don't know how birds perceive the fine structure of song in natural environments, where sound can bounce off trees and buildings, and have to compete with environmental noise.

Recent work has shown that female birds sing as well as male birds, contrary to traditional views of the behavior. The question of whether male and female birds listen to the same song is raised by this discovery. In many tropical species, male and female partners sing duets that sound like a single song. How do birds make sure they produce the correct notes while singing?

The next time you hear a bird, think of it as a fast- moving, precisely coordinated dance of the syrinx, one that is rich in emotion and meaning.