Body size is more important than body shape in determining the energy economy of swimming for aquatic animals, according to scientists at the University of Bristol.

The study shows that big bodies help overcome excess drag, debunking the idea that there is an optimal body shape for low drag.

The large necks of extinct elasmosaurs did add extra drag, but this was compensated by the evolution of large bodies.

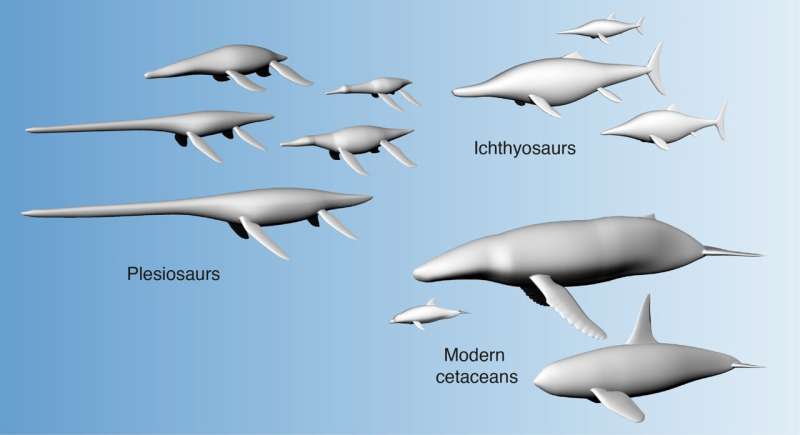

Over the last 250 million years, the four-limbed vertebrates have returned to the ocean in many shapes and sizes, ranging from streamlined modern whales over 25 meters in length, to extinct plesiosaurs with four flippers.

Dolphins and Ichthyosaurs have the same body shapes, adapted for moving fast through water. There were different bodies for the plesiosaurs who lived side by side with the Ichthyosaurs. Their flippers are not the same as those of living animals. Some elasmosaurs had long necks of up to 20 feet (6 meters). The necks were believed to make them slower.

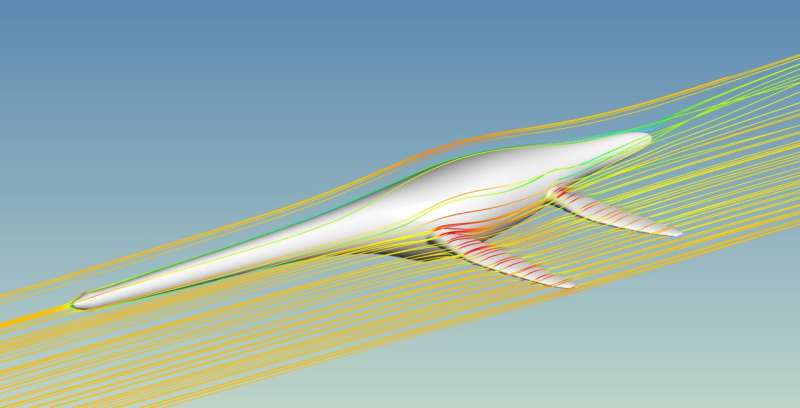

It has been unclear how shape and size influenced the energy demands of swimming in these diverse marine animals. To test our hypotheses, we created various 3D models and performed computer flow simulations. These experiments are done on the computer, but they are similar to water tank experiments.

Colin Palmer, an engineer involved in the project said that the differences between whales and plesiosaurs were relatively minor. When size is taken into account, the differences between groups became much smaller. The ratio of body length to diameter is not a good indicator of low drag.

We were interested in the necks of elasmosaurs and so we created 3D models of them. Simulations show that the neck adds drag, which could make swimming costly. The optimal neck limit lies around twice the length of the animal.

When we looked at a large sample of plesiosaurs, we found that most had necks below this high-drag threshold. We showed that plesiosaurs with long necks had evolved large torsos, and this compensated for the extra drag.

The study shows that long necked plesiosaurs were not necessarily slower swimmers than whales, and this is due to their large bodies. The neck proportions in elasmosaurs changed fast. This shows that long necks were good for elasmosaurs in hunting, but they couldn't exploit it until they became large enough to offset the cost of high drag on their bodies.

The research shows that large aquatic animals can have crazy shapes, like the elasmosaurs. Body sizes can't get indefinitely large as there are constraints to very large sizes as well. The maximum neck lengths seem to balance the benefits of hunting with the costs of growing and maintaining a long neck. In other words, the neck of these extraordinary creatures evolved in balance with the body size to keep it from getting too big.

More information: Large size in aquatic tetrapods compensates for high drag caused by extreme body proportions', Communications Biology (2022). Journal information: Communications Biology Citation: Large bodies helped extinct marine reptiles with long necks swim, new study finds (2022, April 28) retrieved 28 April 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-04-large-bodies-extinct-marine-reptiles.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.