A new database allows researchers to test theories and aid the preservation of birds.

A team of international researchers, led by Dr. Joseph Tobias, from the Department of Life Sciences at Silwood Park at Imperial College London, compiled AVONET. The first iteration of the complete AVONET database and some initial findings are presented in a special issue of the journal Ecology Letters.

The database has already uncovered some information about the evolution and ecology of birds worldwide, and was the subject of a conversation with Dr. Tobias.

Why are bird traits important to study?

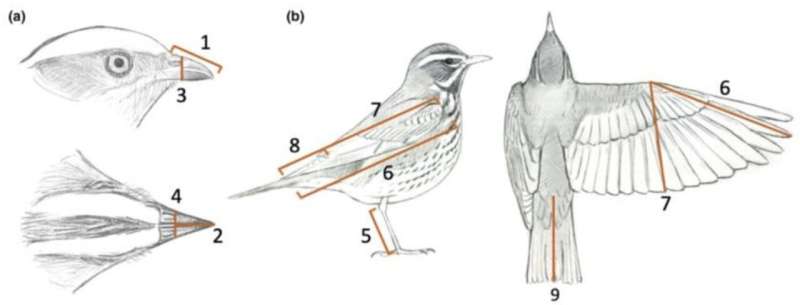

For each individual bird, we measured nine characteristics related to physical aspects of their bodies: four beak measurements, three wing measurements, tail length, and tarsus length. Body mass and hand-wing index are calculated from three wing measurements to give an estimate of flight efficiency and the ability of a species to move across the landscape.

The final version contains data from 90,020 individual birds at an average of nine individuals per species.

These measures correlate with important ecological features of species, including what they eat and how they search for food. Habitat, life history, and main food type are some of the broad categories used in previous studies. Estimates of body size are included in some studies, but the connection between body size and ecological function is not very strong.

For example, how far they travel, and the place in the local food web, are provided by the beaks, wings and legs measurement. Key functional characteristics of bird species, such as their precise diet and their behavior, can be predicted with much greater accuracy by combinations of these traits.

How did the project start?

The publication of AVONET marks the end of a journey. In the 1980s, a schoolboy was walking the tidelines and powerlines of Northumberland in search of bird corpses for dismembering. I owe a debt of gratitude to my mother, who kept bedroom shelves full of skulls and cabinets loaded with tarsi.

The interest in studying bird characteristics to predict ecology has been going on since the 1960s, but it has accelerated in the last decade. Over the last two decades, several research groups compiled and analyzed bird trait datasets of gradually increasing size, initially targeting samples of a few hundred species, and more recently covering thousands of species worldwide.

The raw data has been largely incompatible and unpublished. The goal of the AVONET project is to make the data of bird researchers accessible to the next generation of researchers. The inspiration for the venture was the success of the TRY plant trait database over the last decade.

The data was collected.

Managers of different bird trait datasets joined forces to create AVONET. The completion of this first iteration of AvoNET is a truly international effort, with vital expertise and data contributed by 115 authors based in 106 institutions in 30 countries.

Smaller samples from a further 76 collections were taken from the museum samples, most of which were taken from the Natural History Museum, London and the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

The project rests on the contributions of countless museum curators, field assistants and specimen collector since the mid 1800s, including Charles Darwin, Alfred Russell Wallace, Ernest Shackleton and John James Audubon.

What types of data has AVONET already provided, and what questions could it answer?

Patterns of evolution that appear widespread, but which remain contentious for one reason or another, have been tested by the data. We used it to test the island rule, where animals living on islands tend to evolve into giants or dwarfs in relation to their continental ancestors. The rule explains how the body evolution of animals varies across the Earth's islands, with an effect partly controlled by island size and isolation. There are many other rules that could be investigated.

A study into the hand-wing index showed how dispersal ability varies across all bird species, providing insight into a range of topics such as their sensitivity to habitat loss or their ability to track suitable climates under climate change.

AVONET data can help us understand how the environment responds to change. Initial studies have looked into how bird communities around the world differ in their functional diversity. Estimates can provide information into the condition of useful ecological processes, such as seed dispersal and pest control, and their resilience in the face of changing habitats and climates.

What is the future for AVONET?

More measurement data for each species, as well as more life history and behavioral information, will be included in AVONET 2.0, which will be expanded. We hope that AVONET 1.0 can provide a rich resource for teaching and research in the life sciences.

We hope to use the bird trait data to develop an index of ecological health that can be used in identifying and tracking progress towards effective conservativism.

More information: Joseph A. Tobias et al, AVONET: morphological, ecological and geographical data for all birds, Ecology Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1111/ele.13898A bird in the hand: Global scale morphological trait datasets open new frontiers of ecology, evolution and ecosystem science was written by Joseph A. Tobias. The DOI is 10.1111/ele. 13960.

Journal information: Ecology Letters Citation: Body measurements for all 11,000 bird species released in open-access database (2022, February 24) retrieved 25 February 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-02-body-bird-species-open-access-database.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.