The way a tree takes in sunlight and converts it to energy was learned by the man when he was a child. The man who goes by his given name knows the crops, wild plants, and fruits. The practical methods he learned covered every aspect of farming, from planting field edges with darker crops to creating clear borders between plots. Over time, leave a few trees in the fields to harvest for firewood, animal fodder, or building materials. Spread a mix of grains all over the field to mimic nature so crops have random distribution patterns. A roasted-grain trail mix called kolo, beer, and areki could be made from the mixture of grains.

He is an ethnobotanist at the university. The grains grown there are different from the ones grown in the region of his youth, but the principle is the same. Farmers are good at mimicking nature.

One of the few places in the world where farmers still grow maslins is Ethiopia. The rise of agriculture is thought to have begun more than 10,000 years ago. To lend more complex flavors to breads, beer, and booze, and to be more resistant to pests, these grain mixture are used.

A small group of scientists are trying to change that, as maslins have fallen out of favor around the world. The case for reviving maslins is made in a paper published today in a journal. Why is it taking so much time?

THE GASTRO OBSCURA BOOKDo you like the world?

An eye-opening journey through the history, culture, and places of the culinary world. Order Now

The author of the new paper calls it the Masluminati, a global conspiracy that nobody is talking about. While farmers and botanists are familiar with companion planting and agroforestry, maslins have "flown under the radar for some reason" When he was in Ethiopia, he heard farmers talk about planting teff, sorghum, and other grains together, which made him curious.

The fact that maslins are only grown in Ethiopia and a few other countries is not as significant as it used to be. There is strong evidence that maslins have been growing for thousands of years. The wild wheats may have been foraged before the advent of agriculture. It's difficult to find the first maslin.

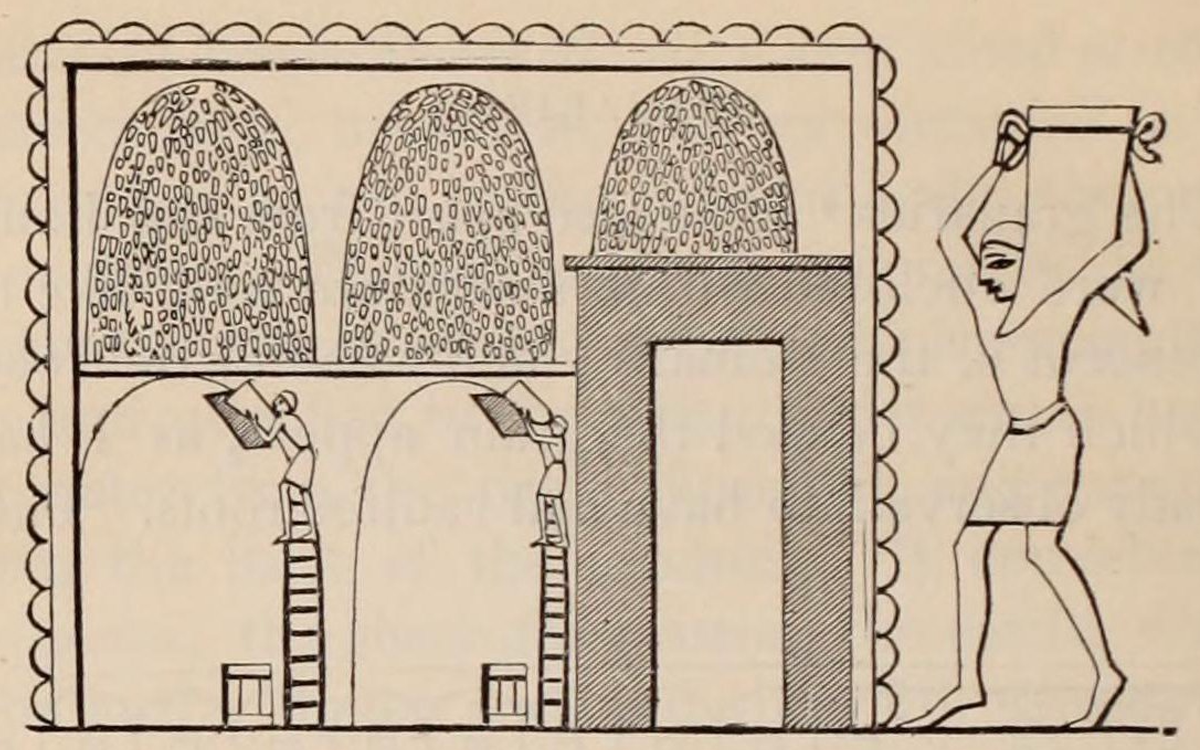

Malleson is an archaeobotanist at the American University of Lebanon. Malleson has studied intercropping in ancient Egypt. To find evidence of early maslins, Malleson and her peers sift through millennia-old middens, which are essentially garbage dumps, and whatever was left behind in hearths and granaries, where different grains may have been mixed together long after harvest.

She says that they were used all over the place. In the past it was scattered all over the place.

The global prevalence of maslins can be heard in the language they are spoken in. Every farming region on the planet had a different way of growing mixed grains.

Farmers in England used to grow a mixture of oats and corn to feed their animals. Pain de méteil, or bread of mixed grains, is a gourmet loaf in France. The local word for maslins was shorthand for anything that was a mixture. The historic word for maslins is surjik, meaning any local dialect that mixes in Russian, Moldovan, or other languages. The word for mixed grains is now referred to as mahlut, a hint about what happened to maslins.

A combination of technological innovations in crop production and processing and the rise of scientific research began in the 18th century. A uniform grain was preferred by the food industry to produce a uniform product. Monocultures were less likely to vary in taste or how they were perfomed. The variability of their characteristics made them less suitable.

From there, the decline of maslins began. The availability of artificial nitrogen for fertilization led to an increase in single-grain crop yields. Most of the world stopped using maslins.

Thanks to a national push to become an agricultural powerhouse, Ethiopia's farmers are feeling the pressure to grow modern crops. Grains should be uniform if they are to be exported. The global market is looking for a specific type of wheat. A mixture of three varieties of wheat and four varieties of barley with some other things thrown in is not a good idea.

With the national embrace of monocultures, new farmers aren't learning the art of cultivating grain mixture, according to Tesfanesh Feseha. She says that young farmers didn't know what to look for.

Although he wasn't directly involved in the new paper, Zemede is still positive. There is a push for modernization. He says that it has technology and attractive things. He understands the appeal of a lucrative offer to grow a specific grain, but thinks that the scientific community should offer better.

Through his research and conversations with farmers, he is trying to promote the maslin tradition. He hopes to inspire wider appreciation of maslins from the people sowing the fields to the urbanites buying an artisan loaf of bread.

As farmers around the world struggle with soils degraded by modern monoculture, a maslin renaissance may be particularly helpful.

“This is about bringing power back to the farmers who understand the land.”

Climate change is supposed to be bad news for small grains. He says that maslins have a number of advantages, including a more reliable yield, a more complete nutrition profile, and the ability to grow in marginal soils. Grain mixes seem to have natural resistance to pests. When a pest is set loose in a monoculture crop, it won't be able to jump from plant to plant if the individual it attacks is surrounded by other types of grain.

The new paper from his team is the first comprehensive case study of growing maslins in the modern era, and other researchers are excited about it.

He was not involved in the research, but he thought the paper was good. He praises it for showing the potential of maslins to meet the challenge of feeding billions on a warming, less stable planet.

Malleson is effusive as well. She said she loved the paper.

Malleson has family members in farming and feels close to the topic of bringing power back to the farmers. The power is brought down to the ground level.

The new paper is a first step towards nudging maslins back onto the world stage. As a boy, he learned about the maslin tradition of Ethiopia, and hopes that more people around the world will follow in his footsteps.

"In biology we say diversity must survive." Diversity will be lost if it is lost.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.