The location where British football analysis found its spark almost a century ago can be found in a military airfield used in World War One.

Sir Frank Whittle studied at the first parachute test centre in the country. It was only a decade ago that Reep arrived as a new recruit.

Reep became a controversial figure in English football history. His innovative studies led to the basis of football data collection and analysis as we know it today, but the motivation behind his work was often misinterpreted.

He was usually stereotyped as a long-ball loving zealot who ruined the game, but his only goal was to uncover football's inner workings and establish the most efficient and attacking style of play, which he arguably achieved to a greater degree than anyone had before.

Reep's impact can be felt 20 years after his death, even in a data-intensive sporting landscape. His reputation does not reflect his accomplishments.

Reep was born in Cornwall in 1904. He joined the RAF at the age of 24 and was posted to Henlow.

It was too far for him to travel to Argyle home games, so he visited Highbury to watch his team. After winning their first FA Cup in 1930, the Gunners went on to win four league titles in the next five seasons.

In 1932, Charles Jones agreed to give two three-hour lectures on football tactics at RAF Henlow. In a drafty hut, beside a large blackboard and easel, Jones spoke about Herbert Chapman's methods for success, apart from a small hiccup when he retired behind the board to adjust his newly fitted false teeth. Reep was making notes in the front row.

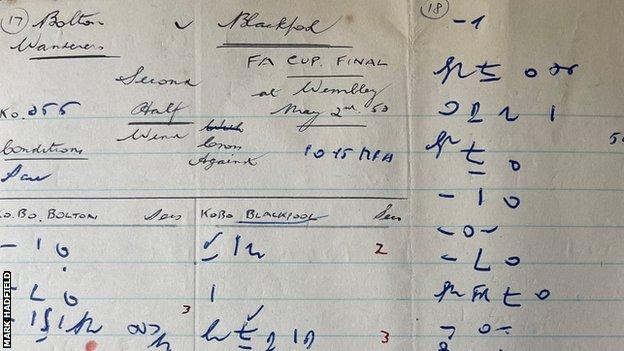

He began to experiment with analytical match notations after Jones talked about how he was watching football. He called his first attempt a tactical crime chart.

He designed a system to grade the difficulty of chances around the goalmouth, which is a very early version of the expected goals metric used today.

Reep took on board the basics of the style of play under Chapman before he died. The players were told to hit the long balls to the wingers. The team would try to win the ball as far up the pitch as possible, with the forwards chasing down defenders in possession.

When Reep was posted to Iraq in 1936, he was put in charge of the base team and implemented the tactics of the other team. The rewards were immediate, but Reep was not able to experiment further because of conflict.

He was the head of football at RAF Yatesbury after World War Two. He had a chance to shape a team around his own design calledLoose Balls in the Goalmouth. The players were drilled to tap in when the ball came across from the opposite flank. Several players signed with league clubs after Yatesbury's success.

When he was posted to Bushy Park in 1950, the station team was urged to follow his ideas, as General Eisenhower had a European base of operations. They were winning games by huge margins, with the wingers scoring hat-tricks.

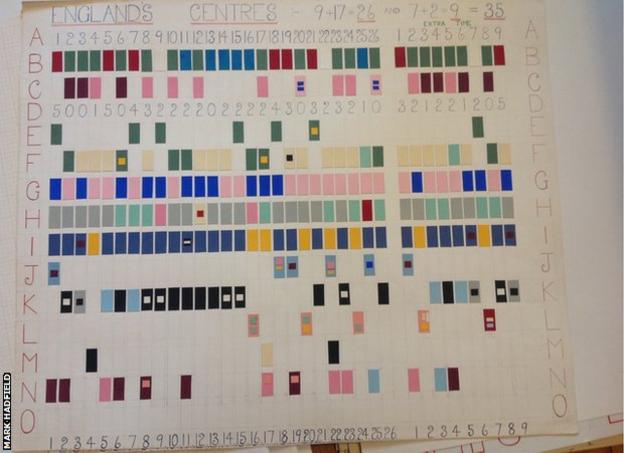

Reep was continuing to collect and analyse football data at the same time he was applying the unique shorthand method he had devised at Henlow to as many First Division games as he could.

He found that seven out of nine goals came from moves of three passes or 888-282-0465 888-282-0465 888-282-0465, and that a goal was twice as likely to be scored when compared to using only short passes to progress up the field.

It took around nine shots to produce a goal, no matter what the standard of play was. His next step was to figure out how these shots could be created. The team had reached a shooting position if they got the ball into the final quarter.

He found that a team would need to score 27 times in the attacking quarter to get a goal, as nine shots were required to get a goal. These were not things that could be relied on in individual matches, but were the averages attained over a series of matches or a whole season.

The deconstruction of the game through numbers was not done before.

He was attracting more attention.

In January 1951, Reep'sRAF team were playing well. The manager of the failing Second Division side needed some help and was five miles away in west London. With no money to spend and a squad low on confidence, he was desperate for inspiration.

Gibbons was told by a scout that the team had recently won.

He reported that there was a crazy fellow who stood on the touchline with bits of paper making notes.

Reep was on the team coach to Doncaster after Gibbons visited Bushy Park.

Since September, they had not won away from home. The first time that a Football League team took notice of Reep's advice was when the Bees won 2-0. Gibbons was happy.

The young manager agreed to follow Reep's plans.

The next match was a victory for Brentford. The press reports described their "whirlwind attacks", which today might be compared to the high-intensity pressing favored by teams such as the Reds.

Reep wrote that it was an unbelievable and instant success. The table was jumping up. After scoring 1.3 goals per game, they won nine of their last 13 matches and finished ninth in the league.

It was just the beginning for Reep.

He contacted the local team, Wolves, after he was posted to the air force. They were led by a physically intimidating man with a nose that had made acquaintances with many centre forwards. He was known to celebrate big wins with a cup of tea.

The 1949 FA Cup was won by Cullis and he was already on his way to great things at Wolves. After meeting Reep, he began working with his wingers on theLoose Balls in the Goalmouth system. Wolves scored 25 goals.

Reep was regarded with suspicion by the directors, who did not understand the fundamental principles that brought the team great success.

Wolves were top of the First Division by early November after a win against Manchester City. They had beaten Manchester United.

The manager was eagerly awaiting the weekly deliveries of charts and tables that Reep would deliver. He had more than 2,000 symbols per match.

He spent Saturday night and most of Sunday hunched over his data, writing his breakdowns on two feet wide sheets of paper.

The data Reep offered was the equivalent of what top-class teams get today. It was as cutting edge as it was at the time.

The Wolves came back stronger the following year after finishing third. Reep felt vindicated when they beat Spurs 2-0 and won the league title. The city of Wolverhampton was overjoyed and Cullis put the kettle on. The great manager publicly thanked his analyst at the civic banquet. The Wolves were one of the teams of the decade and won two titles in 1959 and 1958.

Reep made great progress in the field of football data and analysis after he had been with Wolves for three years. The high point was to be this.

Reep left Wolves for Wednesday in 1955. He had never been employed at Molineux and the job at Hillsborough gave him more money and security. He helped the Owls win promotion to the First Division in 1956, scoring over 100 goals, but left two seasons later when the manager who brought him in was sacked.

In the 1960s and 1970s, he spent time at several other English clubs, but never made it to the top of the English game. His reputation was damaged.

It was thought that Reep only wanted to hoof the ball forwards quickly and without direction, a label he has been tarred with. The style of play he encouraged was the same as before - attackers and wingers were told to make the most of any opportunities.

He believed that winning the ball close to the goal was the most important thing in creating goals, although he wanted to generate as much offensive threat as possible. He began to see positives in possession-based play in the 1990s.

He explained that his methods are not a declaration of how football should be played.

When he was in his 90s, Reep continued to make handwritten analyses of football data. Richard Pollard collaborated with Reep to produce the game's first computer analysis in 1969.

He had an influence on the game in the build-up to the World Cup, but it was not for his own team.

A disappointing draw in Poland in May 1993 meant that England could not afford to slip up in their next game in Norway, four days later.

Reep was held in high regard by Egil Olsen, who was a professor of sports science and had taught the subject for 20 years before taking charge of his national team.

After flying into London and then going to his home in the UK for a five-hour discussion on performance analysis, Olsen became the latest in a long line of football people to seek Reep's advice.

The Norwegian Football Association invited Reep to attend the game against England. Norway played a version of Reep's preferred style.

It is simply an attacking style, but it is called direct football. We push the ball forwards quickly.

The emphasis on offence was the undoing of England as the hosts won 2-0 and went on to win the group and qualify for the World Cup.

The world of football data was moving at a rapid pace when Reep died.

If elite clubs take the role of analysts for granted, Reep should be remembered as the first to make a meaningful intervention at the highest level of the English game.

When he died, there were short obituaries written, but like most of his career in football, his death didn't get much attention.

Reep once said that the English FA dismissed him as an eccentric chap.

I put a question mark against so many aspects of the game.

Many Impossible Things: The Ingenious Evolution of Football Data is a book written by Rob Haywood.