How do we manage it? A group of scientists have a suggestion.

A super-absorbent gel made from inexpensive materials can suck out humidity from the air. The gel releases water when it's heated. A study published in the journal Nature Communications shows that one kilogram of gel can produce more than 13 liters of water at 30% humidity. The Southwest's Mojave desert has a humidity range between 10% and 30%.

Guihua Yu, one of the researchers, said in a press release that the new work is about practical solutions that people can use to get water in the hottest, driest places on Earth. He said that this could allow millions of people without consistent access to drinking water to have simple, water generating devices at home that they can easily operate.

The researchers made the gel from a compound found in all plant cells, a specific fiber from a tuber, and an absorbent salt. The liquid materials were mixed, poured into a mold, left to set for 2 minutes, and then freeze-dried into a thin sheet. The dried gel would cost under $2 if all the materials were used.

G/O Media may get a commission

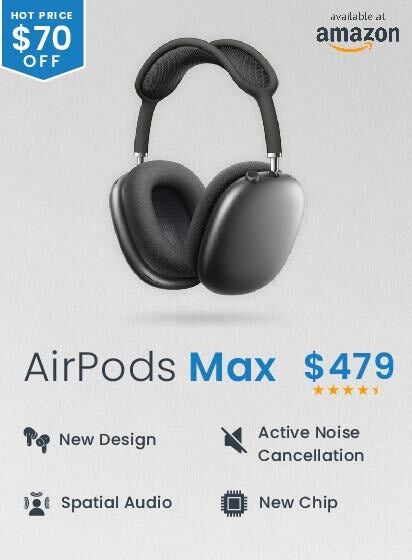

Next-Level Sound can be experienced.

Theater-like sound surrounds you with spatial audio with dynamic head tracking.

The synthesis of this gel is very easy, according to the study co-author.

The thin gel sheets became saturated with water in about 20 minutes. The researchers heated the gel in a closed chamber and collected the condensation to make water. 70% of the captured water was released within 10 minutes of heating the gel.

The gel was tested at different humidities and at different ratios of ingredients. The gel's water absorbance and release capacity were compared with other absorbent materials.

There are lots of things that pull water from the air. You've probably seen those packets inside snack bags and electronics boxes. If you have lived in a humid area, you know that regular table salt absorbs water. French fries lose their crispness over time because of atmospheric water absorption. The new material is different in a number of ways.

It lets go of water relatively easily and absorbs it very efficiently. Desiccants need even higher temperatures than those in the packets to release water. It doesn't add harmful chemicals to the water. The scientists reported that the gel doesn't seem to degrade with repeated use.

We aren't far from a world where the gel can solve the water crisis.

The researchers ran their tests with a small amount of gel and water, and then used the results to make a measurement. It is possible that the water absorption and release capacity changes when the gel is used in larger amounts, according to an email from the author. Wang was not involved in the new research because he has worked on similar water-harvesting technologies before.

The scientists used very thin films of gel in the lab. If this water harvesting technology wants to be used on a mass scale, using a thin material increases the total volume of the device, making it less compact. The gel could be used in larger blocks. They haven't tested that design yet.

Even so, Wang still believes that the new result is exciting because of how little energy input it takes to produce and use. It is significant to achieve water harvesting in a sustainable and low-carbon way.

Wang said the new study has brought nearly impossible freshwater generation in the ultra-dry climate closer to reality.