Animals die after they reproduce. In most species, as the eggs get close to hatching, the mother stops eating. She left her protective huddle over her brood and became bent on self-destruction. She could beat herself against a rock, tear at her skin, or even eat her arms.

The chemicals that seem to control this fatal frenzy have been discovered by researchers. A change in the production and use of cholesterol in her body, which in turn increases her production of steroid hormones, will doom her. Z. Wang is an assistant professor of psychology and biology at the University of Washington.

Wang told Live Science that they are interested in linking the pathways to individual behaviors or differences in how animals express their behaviors.

Wang was interested in female reproduction as a student. She was struck by the deaths of octopus mothers after they laid their eggs when she was in graduate school in science. Nobody knows what the purpose of the behavior is. The theory is that the dramatic death displays draw predatory animals away from eggs, or that the mother's body releases nutrition into the water that nurtures the eggs. Wang said the die-off protects the babies from the older generation. She said that older octopuses could end up eating all of the younger ones.

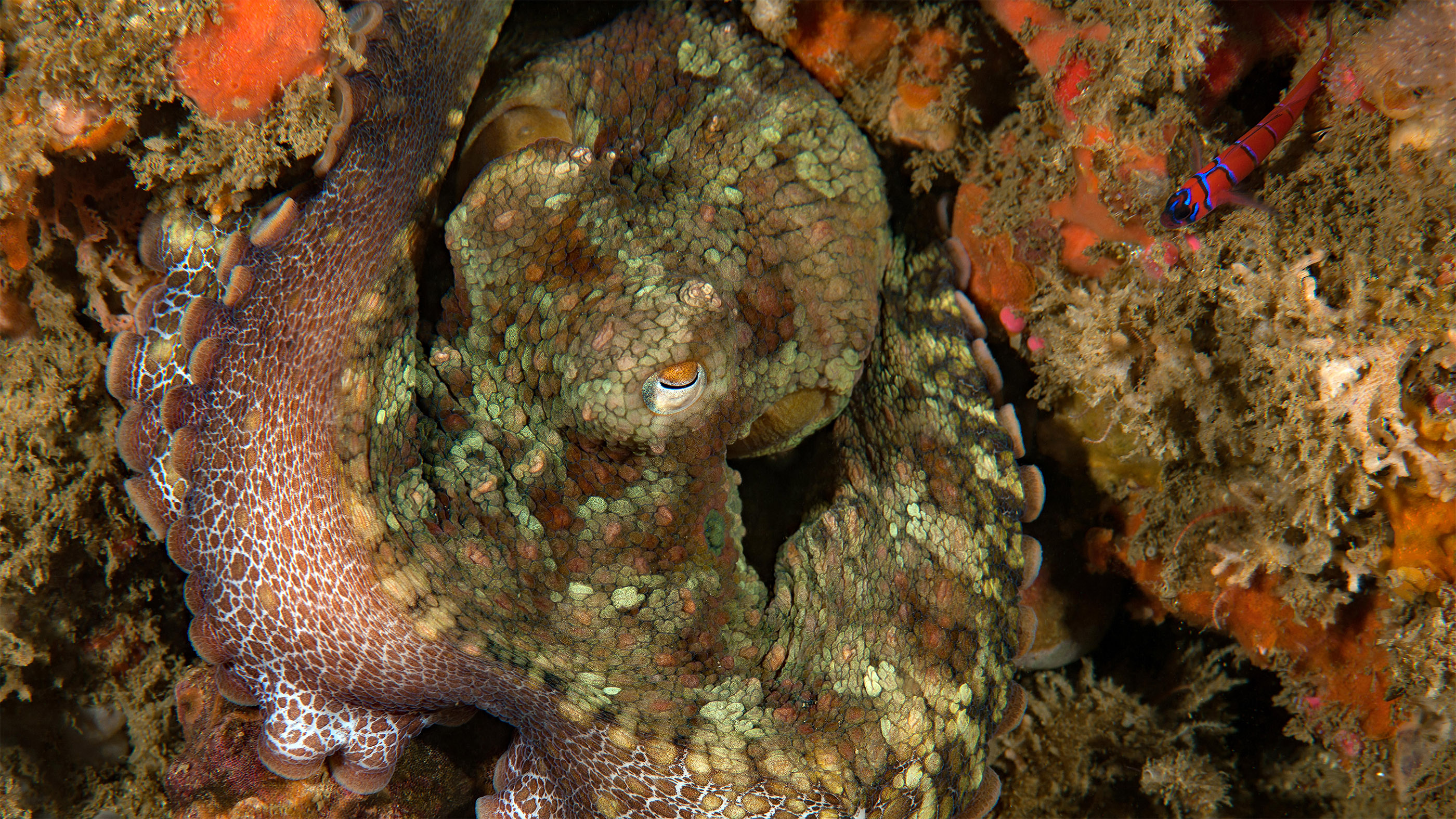

How do octopuses change color?

The mechanism behind this self-destruction was found in a 1977 study by a psychologist at Brandeis University. If the nerves were cut, the mother would abandon her eggs, start eating again and live for another four to six months. That is an impressive life extension for creatures that only live a year.

No one knew what the brain was doing to control self-injury.

Wang said that he wanted to do the experiments that were outlined in the paper that was published.

After laying eggs, Wang and her colleagues analyzed the chemicals produced in the California two-spot octopuses. A genetic analysis of the same species showed that after egg-laying, the genes in the optic glands that produce steroid hormones started going into overdrive. The scientists focused on the steroids and related chemicals produced by the two-spot octopuses.

3 of 3 are images

There were three chemical shifts that happened around the time the mother laid her eggs. Pregnenolone and progesterone are hormones associated with reproduction in a host of creatures. The second shifts were not expected. 7-dehydrocholesterol, or 7-DHC, is a building block of cholesterol produced by the mothers of the octopus. Humans produce 7-DHC in the process of making cholesterol, but they don't keep any in their systems for long, the compound is toxic. Babies born with the genetic disorder Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome are not able to clear 7-DHC. The result is intellectual disability, behavioral problems, self- harm, and physical abnormality like extra fingers and toes.

More components for bile acids, which are acids made by the liver in humans and other animals, began to be produced by the optic glands. The building blocks for bile acids are made by arthropods, but they don't have the same type of bile acids as mammals.

It suggests that it is a brand new class of signaling molecule in the octopus.

The life span of the worm Caenorhabditis elegans has been shown to be controlled by a similar set of acids. It is possible that the bile acid components are important for controlling longevity.

It's hard to study occidentals in captivity because they need a lot of space and perfect conditions to grow to sexual maturity and breed. Wang and other researchers have come up with a way to keep the lesser Pacific striped octopus in the lab. Pacific striped octopuses can mate multiple times and have multiple clutches of eggs. They don't self-destruct as their eggs get ready to hatch, making them perfect specimen for studying the origin of morbid behavior.

Wang said that he was excited to study the dynamics of the optic gland.

The journal Current Biology published the findings on May 12.

It was originally published on Live Science.